Arizona Historical Foundation

Audio By Carbonatix

It’s been roughly a century since the height of Ku Klux Klan activity in Arizona where members donned the infamous white sheets with pointy hoods to terrorize marginalized people.

But there has been momentum in recent months to erase public reminders of the Ku Klux Klan’s membership in the city of Tempe.

At least, that’s the plan.

An unnamed committee with at least 15 members is expected to be appointed by Tempe’s city manager in the next 10 days to rename several streets, parks, and schools.

Cities across the nation have been changing street signs for years in response to community concerns.

Tempe was the flagship city for the Arizona chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, local historic records detail. Jews, Mormons, Catholics, and Latinos were the focus of local Klan campaigns of persecution and intimidation.

“This local KKK chapter was believed to have been primarily focused on anti-Catholic activity, and specifically (was) against Catholic teachers in public schools,” according to a statement on Tempe’s school system website.

It’s unclear whether changing public signs is a trendy version of social justice or if it signals that local government is serious about dealing with existing social issues. Marginalized communities still grapple with the effects of discrimination in housing and police brutality.

Activists say they appreciate the renaming initiative, but “if they think they’ll just do that and nothing else,” the city of Tempe is in for a reckoning, East Valley NAACP President Kiana Sears told Phoenix New Times.

Tempe Takes Action

After three months of debate, the Tempe City Council voted in October to cut ties with five men who were Klan members by stripping four streets, three parks, and three schools bearing their names.

City leaders were concerned about West and East Laird Streets, Hudson Drive, and Hudson Lane, as well as Hudson, Harelson, and Redden Parks.

Laird School, Hudson Elementary School, and Gililland Middle School were also called into question.

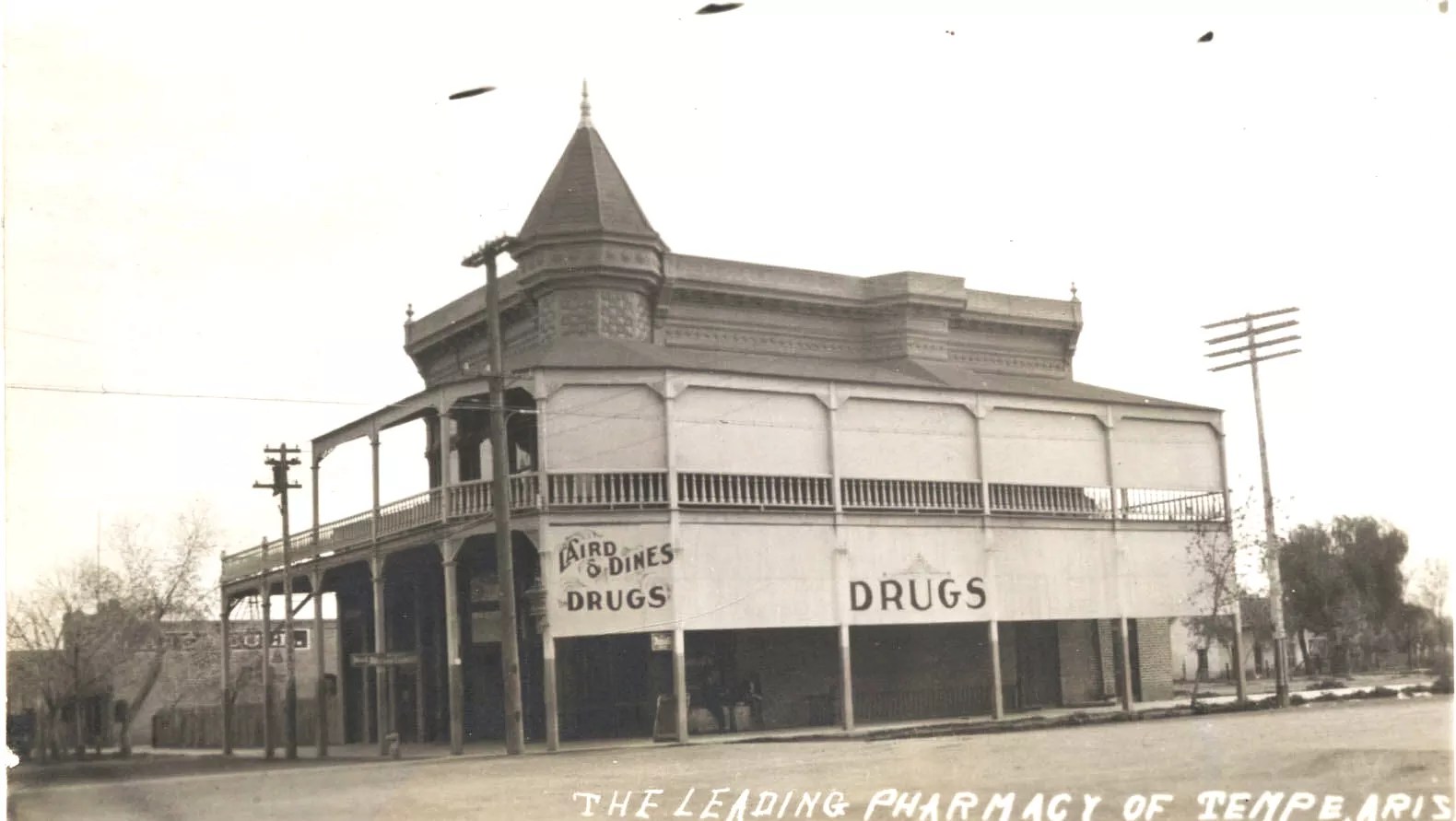

Hugh E. Laird was a longtime mayor of Tempe. He was a pharmacist, operating Laird and Dines Drug Store in downtown Tempe for 66 years. He served on Tempe City Council for more than three decades, two terms in the Arizona State Legislature, and 12 years as Tempe postmaster. He died in 1970 at age 87.

The Laird and Dines building in downtown Tempe, built in 1893.

Tempe History Museum

Harvey Samuel Harelson co-founded the Tempe Rotary Club and belonged to the Arizona Cotton Growers Association. He was a banker and owned an insurance agency in Tempe. He died in 1986 at age 95.

Estmer W. Hudson was a pioneer in the development of Pima County grown long-staple cotton and was largely responsible for the development of the cotton industry in the Salt River Valley. He worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture growing cotton in Phoenix and Chandler. He cultivated cotton and cattle on his 160-acre farm near Rural School Road in Tempe. In 1923, he became a shareholder in the Tempe Irrigating Canal Company. He died in 1972 at age 90.

Byron Alton and Lowell Edward Redden worked for the Tempe Canal Company and served on the Tempe Union High School District Board. Redden built the Valley National Bank at Apache Boulevard and Rural Road. He also built a shopping center at Mill Avenue and Fifth Street that has since been demolished. He died in 1944 at age 78. Byron was a Mason and Shriner and was politically active in Tempe. He died in 1939 at age 67.

Clyde Harlan Gililland was a 30-year veteran Tempe city councilman and mayor. He was president of Tempe Elementary School Board and represented District 3, served as Tempe Rotary Club president, and worked for the Tempe Volunteer Fire Department. He died in 1967 at age 67.

The activist movement to change the public signs has slowed since the fall. At the time, there was fierce opposition and questions about how much the move might cost. Those in opposition blamed “cancel culture” during the city council meeting in October.

But a local self-taught historian, Drew Sullivan, who has studied the Klan in Tempe for about a decade, suggested that those in opposition are misguided.

Klan History

“This is a story that took 50 years to become public,” said Sullivan, who was integral in getting the initiative off the ground.

Klan activity was first publicized in 1922 when Klansmen kidnapped a Mormon school principal in Mesa, beat him, and branded “KKK” onto his face with acid. A Maricopa County grand jury indicted a dozen suspects, but after 125 hours of court deliberation, the case ended with a hung jury.

But the same year, a raid on a Klan base in Los Angeles unearthed Phoenix and Tempe member rosters, Sullivan said.

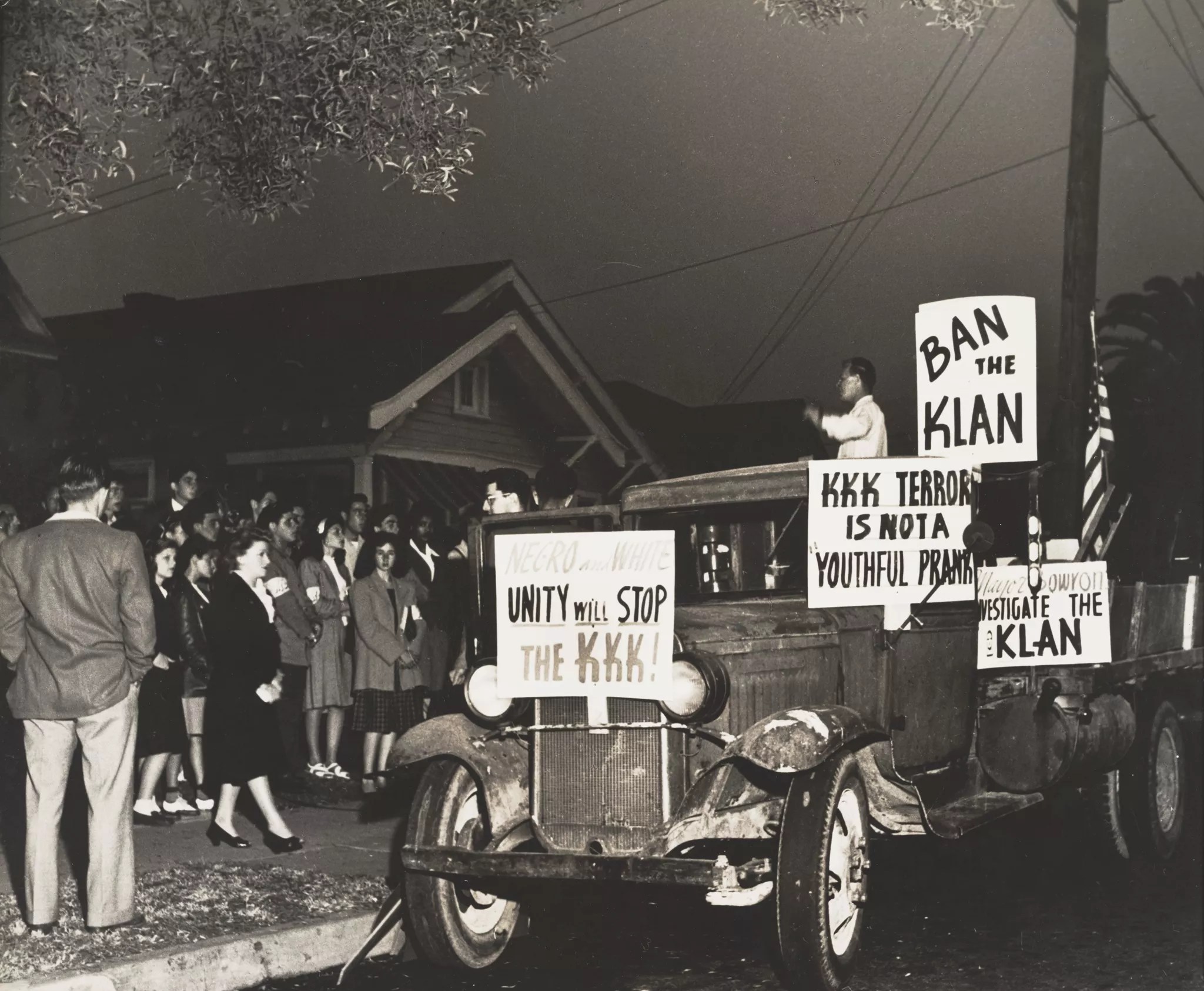

In 1946, there was a protest against the Ku Klux Klan in Los Angeles. The gelatin silver print photo was gifted to the University of Arizona, where it remains.

Arizona Board of Regents

Twenty names were penned on the roster, including Arizona’s then-secretary of state, Ernest R. Hall, according to the Journal of Arizona History. The county grand jury found 18 of those on the roster to be dues-paying Klansmen, after local journalist James Henry McClintock investigated the group. McClintock Drive is named for him.

Joining Hall on the list of suspected Klan members were: the state treasurer, the mayor of Tempe, every candidate for the previous Phoenix City Council election, plus Maricopa County’s sheriff and top prosecutor at the time, according to historic records.

The county attorney later testified he thought he was joining a professional business group, after initially denying membership, records show.

The grand jury probe led to the indictment of an Arizona Gazette editor, a Klansman, for kidnapping and beating a Black shoeshiner in the desert outside Phoenix.

Tom Akers, the editor, was extradited from Atlanta to Phoenix. A Maricopa County jury ultimately found him not guilty, although he later defended the Klan in a newspaper interview, saying, “Thank God for the [Klan’s] courageous and praiseworthy act” in what he called a fair consequence for holding the arm of a white woman.

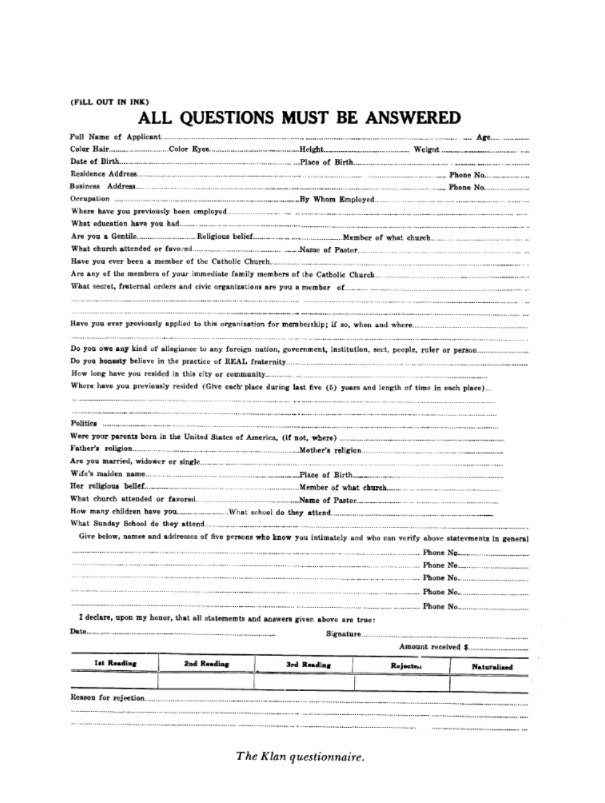

The probe also found the Klan tricked recruits into joining under the guise of “business and fraternal clubs,” including the Cholla Club, the Masonic Lodge of Phoenix, and the Tempe Rotary Club.

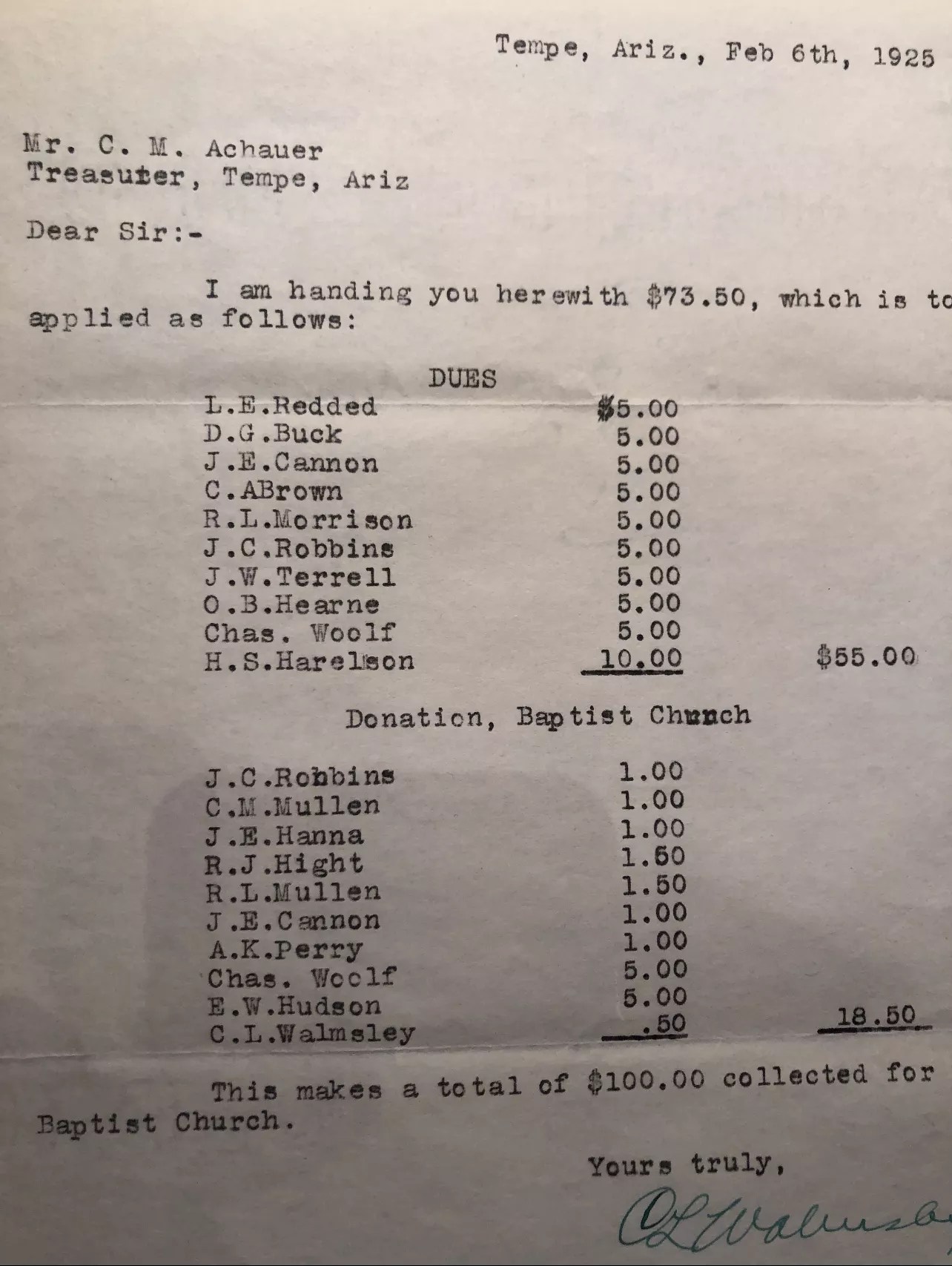

That Rotary chapter was co-founded by Harvey Harelson. Years later, historians found a 100-year-old receipt for $10 in membership dues issued by the Klan treasurer to Harelson. That is what prompted scrutiny of his namesake, the park on Warner Ranch Drive.

“One piece of paper seems like flimsy circumstantial evidence to discredit a founding pioneer of Tempe,” said his grandson, Ted Harelson.

The 11-acre park at Warner Ranch Drive and Myrna Lane in Tempe was named for Harvey Harelson, a supposed Klansman, who died in 1986.

Waymarking

He and several other surviving family members of the five alleged Klansmen have spoken out against changing the signs. Others are against it because of how much it may cost taxpayers.

“It would be premature to attempt to guess” the cost to rename the hot-seat landmarks, Tempe spokesperson Nikki Ripley said.

Tempe City Manager Andrew Ching expects to appoint members to an advisory committee that will meet in the coming weeks, Ripley said. The committee is expected to plan for all aspects of the name changes including estimated costs.

“Bringing this issue forward for community awareness and consideration is the right thing to do,” Ching said. “Together we can acknowledge the past and make purposeful decisions that reflect our community values of equality and anti-discrimination.”

The Klan was active between 1921 and 1925 in Phoenix and Tucson. Klan activity continued in Arizona’s rural mining towns but imploded by 1925. Some called the Klan hypocrites.

“They were strongly devoted to law and order, yet they were law-breakers,” said Sue Wilson Abbey of the Arizona Historical Society.

The Tempe History Museum used records from the historical society and the Phoenix Public Library in its research – the driving force behind the push to change the public signs.

“They spouted Americanism in one breath and attempted to infiltrate state and local governments in the next,” Abbey said.

An editor’s note written in the Klan’s Phoenix newspaper dating back to 1922, compared the Klan’s goals to those of a Masonic Lodge.

“We do not believe that any true American citizen will oppose what the Ku Klux Klan stands for,” the editor of The Crank wrote at the time.

He said the Klan’s goal was “the making of this country a White Man’s country for White Men.”

The Arizona Daily Star had already denounced this, saying in 1921 that the Klan was “in direct violation of all rights of Americans” and a “disgrace to the U.S.”

Hypocrisy led to the Klan’s downfall, according to historians. Klansmen used patriotic and Protestant rhetoric to coerce members, but when the violence began, members bolted.

And that was the end of the Klan in Arizona, historians say.

Not Yet Forgotten

But the Southern Poverty Law Center claims there were KKK groups in Mesa from 2003 to 2005, in Tempe from 2008 to 2010, and in rural Arizona’s Mohave County as recently as 2015.

In 2012, neo-Nazi extremist J.T. Ready recited Klan slogans before killing his girlfriend, three of her family members, and then himself in Mesa, according to FBI documents.

The Western White Knights of the KKK in Arizona had a website and were actively recruiting as recently as 2016. The website has since been taken down.

Arizona Historical Society archivist Isabel Cazares described the Klan records as “rather small.”

In 1924, Klansmen wearing sheets marched in Prescott.

Arizona Historical Foundation

Only records from 1921 to 1925 exist in the half-full file box that is available for public inspection in Tempe.

Harelson doesn’t trust these scant records as proof of his grandfather’s immorality.

Neither does Robert Bowers, a descendent of the Redden family.

“This renaming smacks of woke demagogues arbitrarily, capriciously abusing power in the cancel culture frenzy,” Bowers said in an email.

But activists say it’s more than just a name.

Police Violence

“We need things beyond those symbols removed,” said East Valley NAACP President Sears. “We need a change in policy.”

Officials should start with police policies, she said.

Nationwide, Black people accounted for 27 percent of those killed by police while representing 13 percent of the population, according to the Mapping Police Violence nonprofit. In Tempe, Black residents are 14 times more likely to be shot by police than their white counterparts.

Nearly three out of four arrests in Tempe are for nonviolent crimes, more than state and national averages.

Tempe uses more deadly force against people of color than 95 percent of police departments in America, according to FBI data.

Last year, none of the 83 police departments across Arizona followed through on a single discrimination complaint, FBI records show. Out of 3,000 complaints overall, 98 percent were ruled in favor of the police.

Tempe ranks last in Arizona, according to ratings by the Police Scorecard, a national data clearinghouse for police conduct.

Tempe police used more force, arrested more people for minor offenses, solved murder cases less often, and are less likely to hold officers accountable while spending more on policing overall, according to Police Scorecard.

The Tempe Police Department has not moved forward about any of the nine discrimination complaints it has received since 2016.

In June, Tempe Mayor Corey Woods, who is Black, led a task force of social activists, faith leaders, and retired politicians to address systemic policing issues and the disparate treatment of groups once targeted by the Klan.

Scottsdale also examined its approach to policing in 2020, citing the same rationale.

“We add our voices to those calling for criminal justice reform, a critical step on this most important journey,” Mayor Jim Lane said at the time.

Neighborhoods Divided

South Phoenix hasn’t always had all the luxuries of more affluent places in the Valley. It’s easy to find payday loan joints or discount retail shops there.

The Klan influenced legislation that has kept these redlined neighborhoods in perpetual poverty.

In 1925, the Phoenix Real Estate Board enacted a policy to ban Realtors from selling to “members of any race,” in a way that would be “detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.”

Black residents were barred from living north of Van Buren Street.

After outright racial segregation came housing discrimination for people of color.

Redlining was the practice of denying loans and insurance to those living in neighborhoods bearing “high financial risk,” characterized by low median income and often marginalized people.

In the years following the fall of the Klan, redlined neighborhoods were described as being “very ragged, occupied by Mexicans, Negroes, and the low class of white people,” according to historical descriptions of neighborhoods in Phoenix found on early maps.

The Ku Klux Klan member questionnaire.

Arizona Historical Society

It was those very groups that the Klan targeted.

Restrictive racial covenants corralled the few hundred Black residents at the time to Center City Village and South Mountain, while white owners and renters were free to move in the more desirable neighborhoods of North Phoenix.

“No part of said property shall be sold, conveyed, rented, or leased, in whole or in part, to any person of African or Asiatic descent or by any person not of the white or Caucasian race,” a typical clause in one Arizona deed reads.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled such restrictions are illegal, but they still exist on some older deeds, especially in some of Phoenix’s swankier historic neighborhoods such as Willo or Encanto. Deeds are tied to the land, so such deed restrictions are legally challenging to eradicate, even if they cannot be enforced.

The effects of housing discrimination linger today.

A study last month found Surprise, Peoria, and Gilbert were among the ten worst American cities for minority and low-income lending.

In Phoenix, the rate of Black homeownership is 27 percent, compared to 64 percent for white homeowners.

As recently as 1957, half of Arizona hotels banned Jewish people – a prime target of the Klan. The effects of antisemitic legislation from a time the Klan ruled the Grand Canyon State with near ubiquity and impunity are still felt, according to Debra Stein, who leads the Arizona Chapter of the Jewish Democratic Council of America in Scottsdale.

“The current Arizona legislature uses antisemitic rhetoric,” Stein said. “It should be of major concern to any Jew.”

Her group is concerned that certain state legislators and congressional representatives are associated with white nationalist groups that are reminiscent of the Klan. They often use the Holocaust to leverage comparisons to current affairs like the coronavirus pandemic.

“Antisemitism is deeply entrenched in our politics these days,” Stein said. “Especially in Arizona.”

Before statehood and with the Klan on the rise in Arizona, territorial leaders passed a law mandating that Arizona school children be segregated by race.

Klansmen elected to public office ratified that legislation in Maricopa County as they gained political power in the Valley.

Less than a year after the Klan was ousted from its blip in the mainstream, Phoenix Union Colored High School opened on East Grant Street in Center City. It was Arizona’s first and only Black high school, replacing tawdry, underfunded learning centers and musty basement classrooms in white schools.

Phoenix Schools were desegregated in 1953, just before the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954.

But it didn’t take Klansmen’s names off the schools.

Cost for Justice

The Southern Poverty Law Center identified Tempe as a hub for Klan activity in the state.

And although the group that Congress considers a domestic terrorist threat has historically been linked to Phoenix and Mesa, unlike Tempe, the parks, streets, schools, and landmarks elsewhere in the Valley have apparently been purged of racist insignias.

Phoenix spokesperson Dan Wilson told New Times he wasn’t aware of any tips or suggestions from residents about renaming in the city.

Less than a year ago, Robert E. Lee Street and Squaw Peak Drive in Phoenix were renamed Desert Cactus Street and Piestewa Peak Drive to scrub Confederate and anti-Native links, Wilson said.

It cost the city of Phoenix more than $30,000 to rename that one road. Tempe will need to rename four roads when the project moves forward.

Tempe History Museum director Brenda Abney hopes to see the city reimburse businesses and residents for renaming costs. Taking the lead of Phoenix when it tapped Desert Cactus Street last year, she also advised against naming the landmarks after specific people.

Tempe Elementary School District spokesperson Brittany Franklin told New Times there is no plan in place to rename the three schools – Laird School, Hudson Elementary School, and Gililland Middle School.

Tempe school officials said they have no intention of changing the name of Laird School.

Google Maps

But the district’s governing board “calls for an inclusive process in which all stakeholders will have the opportunity to contribute input regarding the renaming of facilities if that process takes place,” Franklin said.

She couldn’t share how much it would cost to rename the schools if the initiative moves forward.

A single high school in Texas needed $1.8 million to change its name in 2020. A Virginia high school needed $1 million in 2017.

It cost $287,000 to rename each of four secondary schools in Jacksonville, Florida, in 2021.

In Houston in 2016, it cost $150,000 to rename each of eight middle and high schools. And three elementary schools in Virginia took half a million dollars to rename just last year.

Despite opposition, Tempe “reserves the right to rename any city facility previously named, if it is determined that it is in the best interest of the community,” thanks to a 2017 resolution.

Sears, the NAACP president, wants to see the project come to fruition.

In 1925, a receipt for dues paid to a Baptist Church affiliated with the KKK.

Ted Harelson

Those close to the project say it will – for better or for worse.

“They refused to engage me on the subject at all,” said Harelson, who opposes the project. “They’ve already made up their minds.”

He believes his grandfather, who was also a member of the Tempe Rotary Club and the Arizona Cotton Growers Association, was tricked into joining the Klan. The receipt of his dues payment was dated February 6, 1925, as the popularity of the Klan was on the decline in Arizona.

“At that time, the Klan had big defeats in court and in the ballot box,” Harelson said. “Why would my grandfather willingly join as it was collapsing?”

The receipt is issued by C. M. Achauer – the treasurer of both the Klan and the Cotton Growers Association. It was payable to a Baptist church.

Activists say it’s a prime time to consider the hard work and sacrifice needed even for symbolic efforts like this one, amid Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Martin Luther King III, the slain civil rights leader’s oldest son, rallied in Phoenix earlier this month reiterating the national cry to tear down monuments honoring those on the wrong side of history.

“People have given their lives for these changes,” Sears said. “But there’s always a call for more.”