Elias Weiss

Audio By Carbonatix

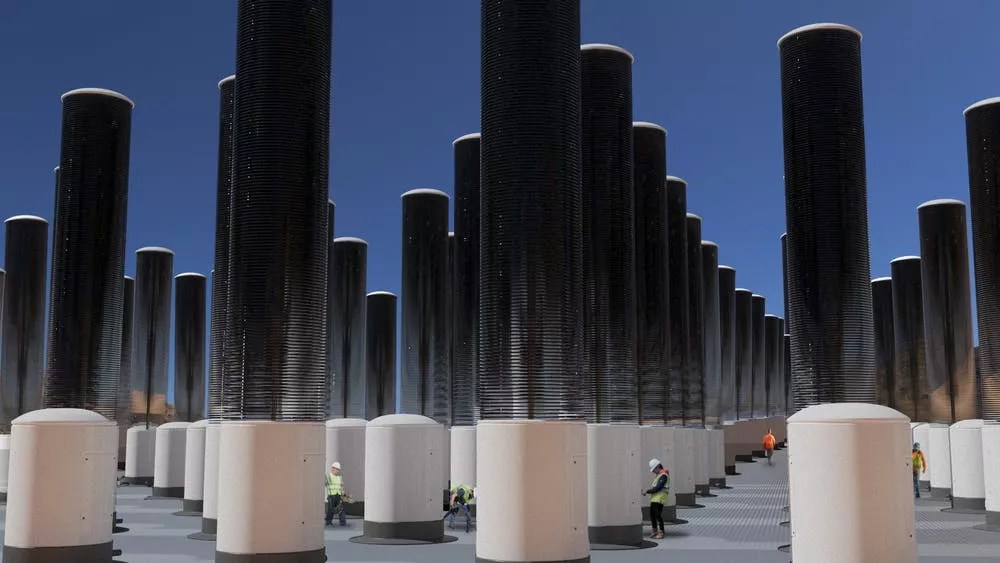

The east side of Arizona State University’s main campus in Tempe is dotted with lofty date palms. Nestled in that iconic desert canopy is a new type of tree that could be the first step in solving the climate crisis.

The MechanicalTree in Tempe stands 33 feet tall.

Elias Weiss

The MechanicalTree near Tyler Street and McAllister Avenue in Tempe won’t help landscape your front lawn nor will one be found growing in any forest.

The 33-foot-tall tree has a stainless steel drum in lieu of a trunk and its leaves are 5-foot metallic discs.

Like planted trees, the MechanicalTree consumes carbon dioxide, the colorless and non-flammable gas that is a leading cause of climate change. This tree, however, consumes 1,000 times more carbon dioxide than its organic counterparts, inventors say.

Scientists unveiled the tree Monday afternoon. It’s the first of its kind in the world, they claim.

“Artificial trees are pretty wild,” said Gary Dirks, senior director of the ASU Global Futures Laboratory. “But they could be our only hope to fight the danger that we as a species face in the climate crisis due to greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.”

The goal isn’t cutting back on carbon emissions anymore. It’s cleaning up the mess the human race has already made.

“Carbon removal is now unavoidable,” said Klaus Lackner, an engineering professor at Arizona State and director of the ASU Center for Negative Carbon Emissions. “We cannot stop the problem anymore by pulling back. We need to clean up after ourselves.”

German environmental scientist and inventor Klaus Lackner, who has been developing the MechanicalTree for more than two decades, speaks at Arizona State University on Monday afternoon.

Elias Weiss

In early 2019, the university announced it would erect the first commercial-scale MechanicalTree that is about to start sucking carbon dioxide from the air.

Lackner has been developing this technology since the 1990s. The German researcher felt like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a Switzerland-based United Nations agency, was “strongly hinting” that the need for carbon-capturing technology was imminent, he said.

He took matters into his own hands.

“There was a desperate need for innovation and I had to figure out how to make it work,” Lackner said.

Dublin-based Carbon Collect Inc. partnered with Lackner on the $2.5 million project in Tempe, bankrolled by a $12 million U.S. Department of Energy program that targets carbon capture and sequestration technologies.

A gentle breeze rustling the tree’s leaden leaves is all that’s needed to generate 1,000 tons of carbon dioxide per tree per day – significantly more than the initial prognosis of just 200 pounds, project scientists say.

The world’s first MechanicalTree on the Arizona State University campus in Tempe can suck in 1,000 tons of carbon dioxide every day.

Elias Weiss

It’s a passive process that doesn’t rely on blowers or fans like its predecessors, meaning it requires almost no energy to be effective.

“Our goal is to accelerate the global climate effort, as set out in U.N. Climate Change conferences to contribute to reversing global carbon emissions,” Pól Á“ Móráin, CEO of Carbon Collect, said last week. “Our passive process is the evolution of carbon-capture technology, which has the ability to be both economically and technologically viable at scale in a reasonably short time frame.”

The trees, each with a lifespan of at least 15 years, are expected to generate enough carbon dioxide to sell at a price of less than $100 per ton. That’s compared to today’s market price of $1,000 per ton.

Lackner said the sheer volume of carbon dioxide harvested by the nascent technology could drop the price as low as $30 per ton.

Carbon dioxide is a needed resource for agricultural workers, the food and beverage industry, automotive manufacturers, and purveyors of synthetic fuels from renewable energy that close the carbon cycle.

“This is the organization that will commercialize this technology,” said Reyad Fezzani, vice chairman and executive director of Carbon Collect. “It’s frankly a daunting challenge. It’s still a new concept and we’re trying to figure out how to make it work.”

Reyad Fezzani, vice chairman of Carbon Collect Inc. in Dublin, speaks at Arizona State University on Monday afternoon.

Elias Weiss

Fezzani was born in Libya and earned a master’s degree in chemical engineering at Imperial College London before his career as an energy executive included a long stint at BP. He said Carbon Collect eventually plans to build a farm of more than 100,000 trees that would collectively harvest 4 million tons of carbon dioxide every day.

Such a farm would mark “a trillion-dollar opportunity,” Lackner has said.

Humans expel more than 36 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year, a notable distortion of Earth’s natural carbon cycle.

An artist’s rendering of the MechanicalTree farm, developed by ASU professor Klaus Lackner and Silicon Kingdom Holdings, a company in Dublin. The farm will act as a passive carbon capture device and is expected to harvest 4 million tons of carbon dioxide every day.

Silicon Kingdom Holdings

The steel sapling has grown to full size since it broke ground in October 2020. It’s on display at Arizona State’s Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory, which opened in December.

The MechanicalTree could be the first step in the excruciatingly long process of not just curbing, but outright reversing nearly a century of global warming.

“It’s a daunting, daunting task,” Lackner said. “Somebody has to do it.”