The proposed mass media campaign, accompanied by posters to be displayed on buses and elevated trains, had been tested at screenings that included both blacks and whites -- to favorable response.

But when the ads finally aired, "The citizens had an absolute hissy fit, especially the African Americans," says council director Paula Haines.

The campaign was denounced as racist, and Haines believes that the comparison of African Americans to two groups so roundly despised by the community was too much to bear. Only two stations aired the spots, but yanked them after the snit hit the fan.

"It was a powerful, powerful piece," Haines says now, but she admits that the council hadn't anticipated the racial backlash.

But it wasn't ready to drop the issue, either. A few years later, the council produced another anti-gang PSA, this time with an upbeat musical message. It won a prestigious media award, which meant nothing, because the message never screened.

"I didn't see the second one air at all," says Haines. "It died an interesting death, and it won this beautiful award."

The state of Arizona collects more than $100 million a year in tobacco taxes. The Arizona Department of Health Services gets about $25 million of that money to spend on anti-tobacco education, and about half of that goes to TV, radio and print ads that include the ubiquitous "smelly, puking habit" campaign. The legislature appropriates another $400,000 a year on advertising to convince young people to abstain from sex.

Although law enforcement agencies say they've counted more than 600 street gangs in the Valley, with nearly 5,000 gang members engaged in a wide range of criminal activity, no one sees fit to craft media campaigns to steer youth away from gang membership.

As the Evanston spot showed, it would not be easy. Smoking cuts across socioeconomic lines, while gangs fester more frequently in disadvantaged minority neighborhoods.

"You don't have the political correctness issues" with smoking, says Malcolm Klein, a professor emeritus at the University of Southern California and internationally recognized street-gang expert.

Furthermore, as Klein points out, gangs have the perverse talent of twisting every message to suit their adolescent egos. Say they're bad, and the gangs agree -- they want to be bad. Send the police to bust their heads, and you're picking on them.

Last month, for example, after the Phoenix Police Department cracked down on the Las Cuatro Milpas gang in south Phoenix, neighborhood residents stood before TV cameras and defended the very criminals who terrorize them against the well-deserved assault by police and press.

And because they flourish in disenfranchised neighborhoods, gangs aren't as visible a problem to the folks who would spend the money to campaign against them.

"Most of the legislature doesn't live in areas where there's serious gang violence or the ever-present trouble of random gunfire," says state Senator Chris Cummiskey, whose district includes some of the toughest gang neighborhoods in Phoenix, "so it doesn't come to mind of those in leadership positions down there. It runs the gamut not just on gangs, but everything you can think of. And that's the trouble with the Legislature: the disconnection to the real world."

"The bottom line," says Linda Bergsma, the Tucson-based chair of Media Literacy, an organization that seeks to educate children to be wary of what they see on TV, "is there's no money for it. There's not the millions of dollars it takes to do really good spots. No one has $4 million to put on an anti-drug or anti-gang-violence campaign."

Which is ironic, because the media, perhaps more than anything, spread gang culture like a computer virus that permeates all levels of today's society.

Youth has always taken its style from the fringes, sending adults into paroxysms and panic. In the '60s, every long-hair in patched jeans looked like an acid-dropping, R.O.T.C.-building bomber to the older generation. In the '80s, we knew a father who swore he'd never criticize his son's hair as his father had criticized his. He kept his promise, but not without a considerable rise in blood pressure when his own son came home with a foot-tall, spiked purple Mohawk.

Now, at the end of the century, rebellion is celebrating the culture of badass.

After the film Colors highlighted urban street-gang life in the mid-'80s, police departments in Phoenix and elsewhere claimed it spawned an upsurge in real-life gang violence, as if gangs needed a primer in how to commit drive-bys.

Gangtsa rap may have incited plenty of white, middle-aged angst when it first emerged, also in the '80s, and though it has faded from fashion, its influence probably makes Tipper Gore long for encrypted Satanic messages that can only be heard when an LP is played backwards. The white group Sublime, for example, lays an upbeat pop melody over lyrics promising to "stick that barrel right down Sancho's throat/ believe me when I say I've got something for his punk ass." Which is not to say that suburban kids are going to run out and "pop a cap in Sancho," but they don't think twice when the singer says he will.

And what to make of cherry-cheeked Ricky Martin gyrating his hips over "la vida loca," a phrase that has served as a longtime street-gang anthem? Mexican-American bangers in Phoenix tattoo three dots on the web of their hands between thumb and forefinger to signify "mi vida loca." There was a gang film by that name. Is Martin singing about gang life? No, but he surely knows where the words came from even if his adoring white audiences don't. The paradox has been the topic of discussion in Hispanic churches in Phoenix.

White teenage girls in Paradise Valley greet each other saying "wazzup," which would be prelude to a fight downtown. The verb "to dis," short for "to disrespect," is firmly established in the American lexicon. Grammarians may argue whether it's really a verb at all; in some neighborhoods it's an insult that could get you shot.

Take a walk through the mall, any mall.

Over at Christown you can buy an acrylic ski cap airbrushed with the words vatos locos, which could mean just "crazy guys." Or it could refer to the gang called Vatos Locos Sinaloenses. You can find numbered or lettered belt buckles to signify your gang's set. The messages could be ambiguous -- in some other neighborhood. But the locals know better than to seem disrespectful to a gang or to raise an inadvertent challenge by wearing the wrong item.

In an all-purpose bad-attitude boutique at Metrocenter, you can find trashy double-wide pants with loops on the thighs to hold your rifle cartridges, a shirt stamped with a prison number or one that resembles the kind of cheap plaids that L.A. street gangs once wore. Down the promenade at Dillard's, one urban sportswear manufacturer markets its line with flashy point-of-purchase displays in which a dark-haired male model of indeterminate ethnic origin shows off the two-inch-high letters tattooed down his arms, letters like those that gangsters array across their backs and chests and torsos.

Police used to think they could identify gangsters by their baggy pants and flannel shirts and bandanas. But given laws that can add years to a criminal sentence if the crime was committed while part of a gang, gangsters don't dress like gangsters anymore. While, in a vaguely derivative way, every other halfway-hip kid does.

On a recent afternoon after school, a white teenaged couple walked through Metrocenter: He could have been Dawson Leary, she could have been Felicity, but they were wearing the widest and saggiest jeans in the mall. He showed a few inches of boxer short, and had his hand in between two layers of tee shirt, a gesture that in neighborhoods he doesn't go to means "I just might be packing a piece." For him, it was an absent-minded stylization.

Hellen Carter, a longtime Maricopa County juvenile probation officer who now heads the department's community-services division, says she once stopped dead in the preteen girls department of a JC Penney store when, on a mannequin, she saw a tiny pair of Minnie Mouse jeans, top button and zipper undone to reveal a couple inches of Mickey boxer shorts, a Mickey bandanna dangling from a back pocket, the epitome of gang fashion.

Gangs have appropriated sports logos -- Oakland Raiders, Dallas Cowboys, Chicago White Sox, Colorado Rockies -- chosen for a coincidence of colors, for the numbers on the jerseys that coincide with the street numbers of the gang sets. If one sees a Raiders cap in Europe or South America, it's not because the owner is a football fan, but because he saw Dr. Dre wearing one on the artwork for an N.W.A. CD.

When New Times asked an Oakland Raiders spokesman how the team felt about having its logo appropriated by street gangs, the spokesman said he'd never heard that, promised to look into it and then never called back.

College professors study street gangs the way they used to study rain forest aborigines, and the analogy is apt, because gangs tend to be small tribal units limited to a relatively small territory.

Near the end of his book, The American Street Gang, Malcolm Klein writes, "Street gangs are an amalgam of racism, of underclass urban poverty, of minority and youth cultures, of fatalism in the face of rampant deprivation, of political insensitivity, and the gross ignorance of inner-city (and inner-town) America on the part of most of us who don't have to survive there."

Gangs tend to spring up in disenfranchised neighborhoods where there are limited jobs and services, few retail stores other than liquor stores, and, as in Arizona, where schools don't get built except by court order. ("Just call the schools 'prisons,' and you'll get all the money you want," one academic quipped.)

It's an interesting paradox that these insulated and isolated cultures can have such effect on the American culture as a whole. Even as the neighborhoods that give rise to gangs are left to wither by the establishment and their denizens relegated to the underclass. Their values and art forms are aped by the moneyed and the middle class. Viewed from a safe suburban distance, the ghetto and the barrio are places of wisdom and cool, of toughness and "street smarts."

The mainstream news media -- which tend to ignore such neighborhoods anyway -- barely know that street gangs exist. Police agencies prefer that news stories omit gang names on the theory that gangs twist even the most negative publicity to their own advantage. The state's largest newspaper, the Arizona Republic, generally follows police policy. The Republic only uses gang names when they are an integral part of the story.

But movies and music and television have spread American street-gang culture so far that there are gang graffiti at the bottom of Havasu Canyon.

"European kids are mimicking American gangs," says Malcolm Klein. "They have Crips and Bloods in the Hague."

The mid-'80s spawned a glut of gangster themes that continued well into the '90s. Gangsta rap devolved out of the angrier reaches of hip-hop, delightfully sinister, alluring to authority-baiting adolescents. Gangsters in MTV videos had style, money, hot women. The genre climaxed, perhaps, with the gangster executions of two of its most prominent performers, Tupac Shakur in 1996 and Biggie Smalls, a.k.a. the Notorious B.I.G., a year later, leaving a pall that in some minds may eclipse the otherwise vibrant, sometimes joyous nature of hip-hop in general.

But it did not go away altogether. Just last month, Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg, now elder gangsta-rap statesmen, appeared together on Saturday Night Live, rapping to an apparently mostly white studio audience. Their refrain: "And I still got love for the street."

Colors, starring Sean Penn, came out in 1985, and moviegoers discovered that bangers make great villains, the kind you want to see blown away in the end. Other films followed: Menace II Society; Boyz N the Hood; Mi Vida Loca; Bound by Honor (video title Blood In Blood Out), movies that built tension to the blow-up point and released it all at once, so that viewers could flow out of the theater thankful that they didn't have to live through it themselves.

For a time, arts writers believed that "tagging," the elaborate urban graffitti form, belonged in art galleries and that taggers were budding artists waiting only to be recognized by the art establishment. Klein, the USC professor, has documented how tagging crews in some cities turned into street gangs when they started competing for wall space with real gangs that were using graffiti to mark territory. The taggers started carrying weapons because they were getting their butts kicked by the bangers.

Klein also has charted the proliferation of gangs in America. In 1950, there were 58 American cities with active street gangs. By 1960, that number had nearly doubled to 101, then nearly doubled again to 179 cities in 1980. But in 1992, there were 769 cities with street gangs, Klein says. Is it a coincidence that the increase occurred after MTV, after gangsta rap, after Colors and Boyz N the Hood?

Well, perhaps. Which is not to say that the media causes gangs, but rather to say that the media legitimizes gangs to the extent that they may more readily develop.

"In areas where the social structure's broken down, how do you garner social structure?" asks Pete Padilla, a sociologist at Arizona State University. "Gangs are a ready-made recipe," he says, and if they are glamorized, legitimized in the media, or just made to seem inevitable, then there may be less neighborhood resistance to their formation.

If the media, especially the electronic media -- inadvertently spread gang culture, there seems little interest to use those same media to combat the spread.

Why can't there be an anti-gang pitch along the lines of the state's flashy anti-tobacco campaign? Because no one wants to pay to advertise against it.

Many public-service ad campaigns come from corporations. Phillip Morris has lately run a series on domestic violence. The National Football League aims ads toward at-risk youth and requires that stations air them as part of game broadcasts. The Wendy's fast-food chain helps support Channel 12's "Wednesday's Child" series as a pet project of Wendy's owner Dave Thomas.

Arizona's tobacco ads stem from a 1994 ballot initiative in which citizens voted to dedicate a portion of the price of every pack of cigarettes to anti-smoking use. That tax produces more than $100 million a year, according to a state Department of Health Services spokesman. DHS spends about $13 million on its well-crafted multimedia ad campaign.

The state legislature appropriates $400,000 a year for advertising to promote sexual abstinence as a form of birth control, but it was not the legislature's idea to do so. Federal welfare dollars have been tied to lowering out-of-wedlock birth rates; abstinence campaigns are the prescribed approach.

"Whenever we start talking about public relations or media campaigns to educate the public about different issues, whether it's teen pregnancy or gang prevention, my colleagues take a fairly dim view," says Cummiskey, a Democrat. "I think it's because they see it as a waste of money."

Public-service announcements differ from paid advertising in that they rely on the goodness of local television stations to air them.

Channel 12, the Phoenix NBC affiliate, for example, receives 200 or so PSAs per week that range from religious messages to theater-company ads, from anti-drug and alcohol messages, to Air Force enlistment pitches. The station tries to play 15 per day, mostly late at night or in the wee hours of the morning.

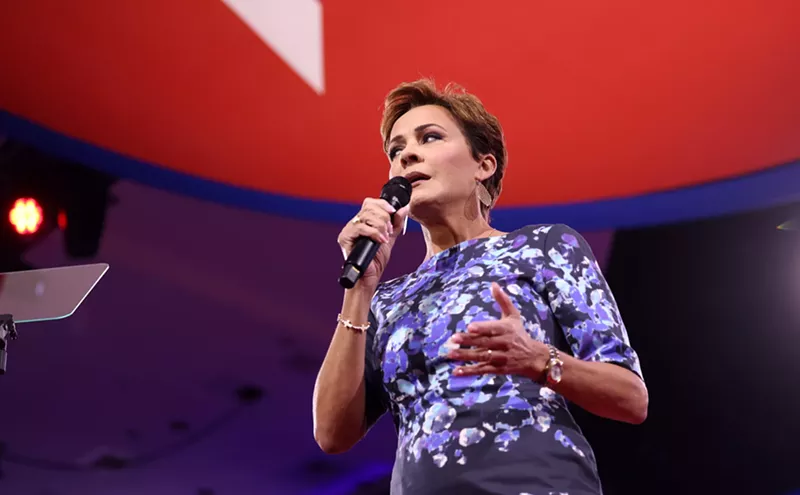

"I'm not going to air something that's going to stereotype our communities in a negative way," says Lucia Madrid, the station's vice president for community relations, explaining why a pitch like Evanston's anti-gang PSA might not pass muster. However, trying to put a positive spin on a negative problem can result in a frivolous message, as the Evanston Human Relations Council found in its second PSA.

Similarly, in 1993, the Phoenix chapter of Mothers Against Gangs produced Spanish- and English-language anti-gang PSAs aimed at preteens. In the spots an adult Hispanic thrashes his arms about while stiffly mouthing bad rap rhymes. The result is laughably unsophisticated.

"It only showed dancing," says MAG's Sophia Lopez-Espindola. "It didn't really show the effects of what gangs can do, and that's what I think they need to show. Although it's hard to see a dead body there, people actually need to see that. And the kids, this is what's going to happen to you."

In the end the PSAs' ineffectiveness was moot, because they only aired about 2 in the morning, Lopez says, rather than at a time when kids might actually watch them.

"Obviously, if you had the same kind of budget that the tobacco companies have, you could probably have a very similar impact," says Captain Mike Orose of G.I.T.E.M., the Department of Public Safety's gang task force.

There are PSAs aimed at a larger group of troubled young people, not just those who might join gangs.

The Phoenix Suns, for example, are preparing a new PSA to publicize their Nite Hoops program, which enlists young adult parolees in a program that combines citizenship and parenting and job-hunting classes with a basketball league and trips to pro games. The Suns will likely have the clout to get their spots aired during prime time.

The National Crime Prevention Council together with the National Ad Council has put together remarkably sophisticated PSAs both to appeal to kids and to shock them.

For example, one spot, while talking about gangsters and crackheads, depicts a group of "fringey" kids with tattoos and frowning faces. Then it turns the tables to say that these are good kids trying to reform bad kids. The positive parting message: "Judge us by what we do, not by how we look."

Another shows a chilling montage of child gunshot victims, funerals, mourning relatives and actual footage of youths chasing each other down city streets while firing handguns. A sweet gospel soprano sings "Where have all the children gone," to Bob Dylan's timeless "Blowing in the Wind."

"I do peace treaties [with gangs] all over the country," says Jerel Eaglin, director of youth services for the Washington, D.C.-based National Crime Prevention Council.

"Almost 80 percent of gang members want out," he contends.

Eaglin claims to be a former gang member himself. He also goes by the Muslim name of Muata Kiongozi, and he travels the country making inspirational speeches about gangs and gang problems.

Despite the MTV views of "gangsta paradise," it's really a life of gangsta hell.

"The moment you sign up, you have signed your death warrant," he says.

Gangsters live in a constant state of posttraumatic stress, watching their backs, waiting to get whacked. And unlike the posttraumatic stress suffered by soldiers, there's no going home, no getting off the plane and kissing the ground.

"I got kids planning their funerals," Eaglin says.

And so his solution for anti-gang advertising is simple, but dramatic.

"What I'd like to see on TV, is 'How Do You Get Out?'" he says.

Merely telling kids to stay away from gangs -- or anything else -- is futile. Push too hard, and you drive them toward exactly what you're telling them to avoid.

Eaglin cautions that any anti-gang message needs "aftercare programs." Like the Suns PSA, it has to be tied to something meaningful.

Media alone can't do it. If you tell a gangster to stop being a gangster, you have to provide an option, a place to go instead of the street, a job, an education, a viable way out.

Read more stories in the Hard Core series.

Contact Michael Kiefer at his online address: [email protected]