New Times Illustration (Adobe Images)

Audio By Carbonatix

Maria Alvarez’s home was abuzz with activity.

Generations of family members milled around the front yard of her Guadalupe house one breezy February day, drinking sodas and picking at a Little Caesars pizza on a folding table. In the driveway, toddlers rollicked, driving miniature electric cars and intermittently howling. These were Maria’s great-grandchildren, and whenever they got out of hand, the 73-year-old reined them in with a great-grandmotherly admonishment.

“Go talk to Tata Sergio,” she said in a stern but loving voice. “He don’t like you behaving that way.”

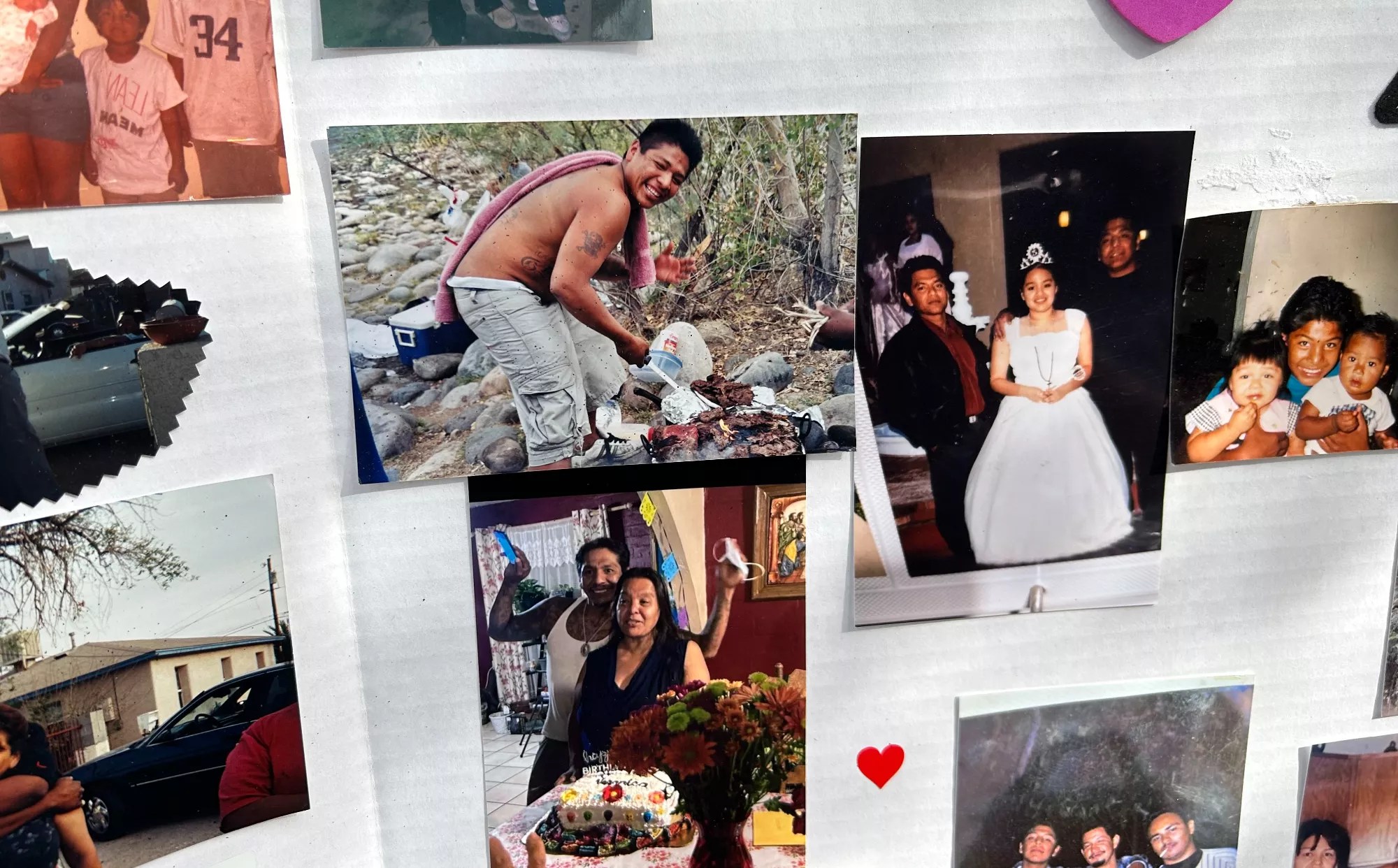

The tata in question was Maria’s son, and he wasn’t there – at least not physically. But Sergio Alvarez’s presence hung over the gathering. Maria had directed the rambunctious tots to two nearby poster boards, each plastered with photos of Sergio over the years. More were to be found on the table, in photobooks and journals documenting his life. Sergio’s premature death left the Alvarez family, including his six children, with countless questions about his demise.

On May 28, 2024, roughly nine months before the get-together in Guadalupe, a Phoenix police officer had shot and killed Sergio in a late-night encounter that remains shrouded in mystery. Publicly, police said they stopped Alvarez over a bicycle light infraction. But police records show police used the bike light as pretext to stop Alvarez because he was riding his bike near “a drug house.”

The stop ended with three bullets tearing through the 48-year-old’s body. In between, police said Sergio managed to shoot an officer despite being pinned to the ground by two cops.

How that happened is not clear. The body-worn cameras carried by both cops fell off during the encounter. As a result, footage of the incident released by the department captures almost nothing – just audio from the struggle. The department’s video briefing does not include footage indicating how the stop escalated.

Now, a full year after Sergio’s death, his loved ones remain tormented by all they don’t know about his final hour. Reports and records they’ve obtained from police provide few satisfying answers. The one snippet of his final moments that the family has actually recovered – nearby security camera footage from after the shooting, which shows officers kicking the thrice-shot Alvarez and waiting several minutes to render life-saving aid – has only sharpened the family’s grief.

Because the police narrative is that Sergio shot first, his family members said, lawyers have declined to help them build a case against the department. Instead, like so many families who have lost loved ones to Phoenix cops and their service weapons – and there are an alarming number of them – they are left mostly with the weight of their unimaginable loss, an open wound that may never fully close.

“I don’t know why, why, why. They could have just hit him in the leg or the arm,” Maria cried, holding back tears and thinking of the rowdy children in the driveway. “He’s missing his grandbabies. He should be here.”

A collage of photos of Sergio Alvarez outside Maria Alvarez’s home in February.

TJ L’Heureux

Checkered past, new start

The bicycle Sergio was riding that night was a common and welcome sight around Guadalupe, a town south of Phoenix of 5,000 predominantly Latino and Yaqui residents. Just like norteño music and the starch-white Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church, Sergio and his bike were a fixture of the dry, dusty community, where the median household income is about 25% lower than that of Phoenix.

“He used to cruise around with his bike, back and forth,” said Jose Tavena, who lives down the street from Maria. “He would come over and pull over and say hello to everybody, shake everybody’s hands.”

A calm, large man with a soothing baritone voice, Tavena has been in the neighborhood long enough to remember Sergio’s childhood. As a kid, Sergio was charged up with energy, playing baseball and running around town. As an adult, Tavena and others said, Sergio was thoughtful and eager to please.

A neighborhood stroll with Sergio could take ages, there were so many people he stopped to greet. “It’d take a long time to get down the street,” said Chrissy Gutierrez, Sergio’s high school sweetheart and the mother of his children. Frequently, he’d offer more than just a hello. “He’d say, ‘You guys need some more beer?’ and would go to the store and bring a 12-pack,” Tavena said. “Sometimes he would bring meat or steaks for us to grill.”

Renee Alvarez, who married into the family and lives in Guadalupe, said Sergio would “always make sure somebody had something before he did. Even somebody that would be laying in the street. I’d see him go to the store, buy him some food, make sure he’s up.”

Generous and kind as he was, Sergio “had his own struggles,” his 28-year-old daughter Destiny said. His run-in with the cops last year was hardly his first. Court documents from a 2015 case note that Alvarez had been arrested at least eight times, most often for marijuana possession and resisting arrest.

Mercedes Alvarez comforts her grandmother, Maria, as she talks about losing Sergio Alvarez in a police shooting.

TJ L’Heureux

In 2010, he and Chrissy got in a heated argument that led to a 911 call for domestic violence, though Chrissy told officers he had not harmed her. Alvarez fled the house and threw a bag of weed on the roof, which officers found. He was ultimately sentenced to a year in prison for the drugs. In 2015, Sergio was charged with trespassing and aggravated assault for allegedly beating up a woman, landing probation and paying restitution. A year later, he was booked for a DUI while driving a child younger than 15. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to more than three and a half years in prison.

The DUI was Sergio’s last run-in with the law before his death. Since he was released early in 2019, he had been motivated to stay out of trouble and “do everything right for us,” Destiny said. Prison and the separation from his family had been rough. “He did not want to go back,” Destiny said. After he got out, she noticed a change in her father’s demeanor.

“He was just present. He’d take the time to know where we were mentally and emotionally and where we wanted to be in life,” Destiny said. “He asked a lot of questions that made me know he was working to be a better person.”

Sergio was interested in Yaqui mythology and believed in a higher power. He talked about starting a YouTube channel to share his life experiences. Destiny and her 25-year-old sister, Isla, remember their father always laughing and eating. Especially eating. Sergio’s appetite was so ravenous that his grandchildren started calling him “Tata Chicken.” Sergio would laugh at the moniker – and then take his grandkids to get some chicken.

His post-release life was hardly carefree, of course. After his release, Sergio worked for four years at a construction company and then at Tempe manufacturer Coxreels, but he had been out of work for about a year before his death, Destiny said. He mainly helped Maria around the house. Outside of it, he felt constantly harassed by police, and his own history with law enforcement plagued his thoughts.

“It looked like they always picked on him,” said Renee. “He didn’t do nothing, but he would get mad and ask, ‘Why are you following me?'”

There’s no indication that the Phoenix cops who stopped Sergio on his bike had any knowledge of his criminal history. But his sour history with the police may have been on Sergio’s mind. Though the body-cam footage of his fateful encounter with Phoenix officers doesn’t reveal much, Sergio can be heard asking for one thing over and over:

Help.

Police said Sergio Francisco Alvarez fired the above handgun at officers after he was detained for a traffic violation on his bicycle.

Phoenix Police Department

Playing a hunch

In the early morning hours of his last day on Earth, Sergio was biking to the house where two of his kids – Isla and Sergio Jr. – lived in Phoenix, Destiny said. According to a police report, he was wearing a red shirt with Al Pacino as Scarface on the front.

Phoenix police officers Peter De La Pena and Andrew Estrella stopped him near Southern Avenue and 10th Street, allegedly because his bike was missing a required light. However, the police report reveals that both officers told a detective investigating the shooting that they “knew a few drug houses” in the area and Alvarez “did not have a bike light on,” so they “decided to stop and talk” to him.

A pretextual stop is one in which a “police officer identifies an objective violation of a traffic law, the officer may lawfully stop a motorist – even if the officer’s actual intention is to use the stop to investigate a hunch that, by itself, would not amount to reasonable suspicion or probable cause,” as the Stanford Law Review wrote in 2021. They were ruled constitutional by the Supreme Court in 1996, though there have been efforts in many states to ban or limit them in the decades since. Studies have shown that police conduct pretextual stops of racial minorities – which Sergio certainly was – at a disproportionate rate.

The two officers spoke to Sergio through a window of their Chevy Tahoe, the police report said. They asked his name. De La Pena told an investigator that Alvarez “provided a name of ‘Sergio’ something,” which De La Pena incorrectly assumed to be a fake name. In part based on what they perceived to be Sergio’s shiftiness and unwillingness to identify himself, the two officers exited their vehicle and told Sergio they were stopping him for the bike light infraction.

At least, that’s what the police report says. If the two officers did in fact tell Sergio the reason for the stop, it’s not evident in the body-cam footage released by the department as part of a “critical incident briefing” after his killing. The video starts in the heat of action, with Estrella rushing out of the driver’s side of the Tahoe to the opposite side, where De La Pena could be seen pushing Sergio up against the car. When the audio begins playing after a delay, Sergio can be heard screaming.

“What are you guys doing?” Sergio asked, only to be told that he’s “under arrest” and to get on the ground. “For what? I haven’t done shit to you guys,” Sergio said. “Do I have a warrant or what the fuck?” The officers did not reply.

The rest of what happened is barely visible – police said one officer lost his body camera at the start of the interaction, while the other lost his when Sergio was wrestled to the ground. From that point, all that can be seen is a jostle of bodies in one corner of the frame. After the shooting, both officers told investigators that Estrella was on top of a face-down Sergio while De La Pena was wrestling with Sergio’s right hand.

Though not much can be seen in the body-cam footage, much can be heard. Sergio continued screaming for help and told the officers to get off him and stop choking him. “I’m not,” one officer replied. “Stop grabbing my hand.”

“I can’t breathe,” Sergio said, his voice muffled. Then, about 80 seconds after the body-cam footage began – right after Sergio shifted his weight onto one hip, Estrella told investigators – a shot was fired. Speaking to an investigator from the hospital after the shooting, Estrella said it sounded like a balloon loudly popping.

“He shot me,” Estrella said twice.

Speaking to investigators afterward, De La Pena said he saw a gun in Sergio’s left hand, which Estrella said earlier had been extended – and empty – above his body.

“Put it down,” De La Pena ordered. “Put it down now.”

De La Pena ordered Estrella to step back and radio for assistance. Then, he told investigators, he put the muzzle of his service weapon to Sergio’s back and fired. De La Pena said he fired two shots, though the medical examiner’s report said he was shot three times – in the shoulder, jaw and neck. “Stop, or I’m gonna shoot you again,” De La Pena commanded. Sergio continued to moan and scream.

At the end of the video provided by police, he again asked officers, “Why did you stop me?” The officers did not reply.

Security camera footage acquired by the Alvarez family shows what happened after he was shot.

Courtesy of the Alvarez family

The shooting and the aftermath

Exactly what happened in that roughly two-minute span may never be fully known, at least outside of the official police narrative. Did Sergio really manage to “pull out a handgun and fire it” while being dogpiled by two cops? If he did, why? The record leaves only the recollections of De La Pena and Estrella. Phoenix New Times requested all body-cam footage from the incident, but was not provided any footage that showed how the interaction between Sergio and the two officers began.

Sergio’s family has filled in one gap, although hardly to their satisfaction. In both an advisory issued soon after Sergio’s death and in the video briefing published two weeks later, police said Sergio was able to stand up and walk away from the officers before being taken into custody, at which point he was given emergency medical aid. But that brief narrative glosses over much of what happened after Sergio was shot.

Records indicate that De La Pena was busy trying to give aid to Estrella and let Sergio walk away because he had dropped the gun and knew other officers were responding. Security camera footage from a nearby building, obtained by Sergio’s family, shows much of what happened next.

(Though police sometimes include such footage in critical incident briefings, it was not included in the public briefing on Sergio’s death. The department claimed it had no surveillance footage related to the incident in response to a records request from New Times.)

The footage shows that Sergio stumbled away after he was shot. He appeared to be in a stupor. When a squad car pulled up, he raised his arms. No weapon was visible in his hands, just a cell phone. According to the police report, Sgt. Brent McElvain walked over and sent Sergio to the ground with a forceful kick. (McElvain told investigators that he activated his body camera while driving up, though no footage from it was included in the department’s public briefing. The department said it is still working on producing that footage in response to New Times’ records request.) Two more cops joined McElvain, kicking and pummeling Sergio for about 30 seconds before ultimately handcuffing him.

Then, for roughly seven to 10 minutes – it is difficult to tell, based on the grainy security camera footage – three or four officers stood over Sergio’s squirming body. One officer told investigators that he quickly started rendering aid to Sergio by stuffing his gunshot wounds, though it’s difficult to tell from the surveillance footage exactly when that happened. As time passed, more officers arrived on the scene, walking around the car-swarmed street. After a few minutes, Alvarez’s body stopped moving. At that point, the footage shows an officer performing CPR on Sergio for about a minute before paramedics arrived.

According to hospital records signed by doctors at Valleywise Health Medical Center, Alvarez likely died at 3:24 a.m., roughly three minutes after the ambulance left the scene. He was pronounced dead at 3:42 a.m., shortly after arriving at the hospital.

A photo, taken by Phoenix police, shows the aftermath of the shooting of Sergio Alvarez and officer Andrew Estrella.

Phoenix Police Department

Police files say police recovered two guns – one that was left on the ground by the bicycle, missing one bullet, and another in Alvarez’s backpack. They also found two magazines of ammunition, a small baggie of a clear substance that they believed to be methamphetamine and a bag of blue pills they thought were fentanyl.

New Times sent questions to the department about whether the bullet that hit Estrella matched the bullets in the gun recovered on scene, and if any fingerprints on the weapon matched Sergio’s. New Times also asked if the substances found in Sergio’s bag were what police suspected. Donna Rossi, the department’s director of communications, declined to answer.

New Times also asked the police department for the results of its internal investigation into the shooting but has not received them. Records show the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office declined to bring charges against De La Pena for shooting Alvarez – but the office noted that no other officers involved were investigated.

Destiny said that while the guns and ammo found on Sergio were not a surprise to the family, the drugs were. “I knew about the guns,” she said. “He used to do drugs before he got out of prison the last time, but it didn’t seem like he was using them. We didn’t know anything about him having them.”

The shooting isn’t the only thing that troubles the Alvarez family. Sergio’s daughters are disgusted by what happened after.

“Instead of helping him, they’re kicking him,” Destiny said. Isla called the police response “fucked-up” and unnecessary.

“They were beating him up while he was already down,” she said, “and already shot.”

The Alvarez family learned of Sergio’s death at 9 a.m. later that morning, when a Phoenix police officer rolled up to the house of Sergio’s sister – named Maria, like their mother. According to the police report, the cop was accompanied by Maricopa County Sheriff’s deputies due to “anti-police sentiment known to the deputies from the suspect’s family.”

Nothing aggressive happens in an audio recording of the encounter released by police, which lasts about seven minutes. But it makes for difficult listening. The younger Maria answers the door brightly, making pleasant chatter with the officer. Eventually, the officer apparently shows her a photo of Sergio.

“Is that your brother?” he asks.

“Yes…” Maria responds.

“I’m sorry,” the officer says. “He’s passed away.”

“No…” Maria says. “How?”

As the officer explains the circumstances of Sergio’s death, Maria breaks down crying. Gasping for breath, she asks a few questions – where to identify Sergio’s body, where he was killed. The officer asks if there’s anyone she needs to call.

As she sobs, he offers his card.

“I wish this had never happened,” he says.

Maria Alvarez sobs with a great-grandchild in her arms while remembering her son, Sergio, at her house on Feb. 8, 2025.

TJ L’Heureux

Questions remain

More than a year has passed since then, and that shock and grief persist.

Sergio’s mother has refused to watch the police videos documenting the death of her son. Renee has watched them and called the footage “disgusting.” Isla is suspicious about the beginning of the interaction between her father and the officers.

“You can tell what their intentions were, and that’s why he yelled the way he did,” she said.

Skepticism of law enforcement is typical in Guadalupe. The Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office patrols the community, which was the focus of many unconstitutional immigration sweeps under former Sheriff Joe Arpaio. The sheriff’s office has been under court-ordered oversight since 2013, and by the end of the year will have spent more than $300 million bringing the agency into compliance with a federal judge’s orders, much of it spent working to clear a backlog of internal affairs complaints and to correct a pattern of racial profiling in traffic stops.

“They haven’t just done it to him,” Renee said. “There’s a lot going on with these cops.”

The Phoenix Police Department is a separate entity, of course, but is just as pockmarked. A recent study showed that Phoenix cops have killed 173 people since 2013, the second-highest death toll of any department in the country. Between 2008 and 2018, Phoenix approved $26 million in settlement money for police violence in 191 cases. In November 2023, the city paid $5.5 million to the family of Ali Osman, who was killed after throwing rocks at an officer during a mental health crisis in September 2022.

Just weeks after Sergio was gunned down, the U.S. Department of Justice released a 126-page report that found that Phoenix police regularly committed a litany of civil rights violations, including discriminating against people of color and using excessive and unnecessary deadly force. Notably, given how police responded after shooting Sergio, the DOJ also found that officers “unreasonably delay rendering aid to people they have shot, and at times use significant, unreasonable force against people who are already incapacitated, sometimes even unconscious, as the result of police gunfire.”

While questions remain about the justification for shooting Sergio, what’s clear is that his family has felt left in the dark after his death. Destiny said the Alvarez family paid more than $2,500 – a substantial sum for the family – to get public records and video footage related to his killing. Most of it still has not been released to them, they say.

Destiny said the family finally got Sergio’s phone from police in the spring, which they believe their father might have used to record after walking away from officers. But Destiny said the phone was wiped of most of its content when they received it. It had no pictures and no history of messages. Officer Wesley Thompson, one of the cops who responded to the shooting scene, noted in the incident report that he kept the phone charging so police could have the option of extracting its contents as evidence.

The statute of limitations for a wrongful death suit in Arizona is two years, so the Alvarez family still has time to find answers and pursue a case. But while other victims of police violence have mounted successful civil claims against the city, that appears to be a dead end for the Alvarezes. Destiny said several attorneys – including Bob McWhirter, who has represented many clients and families in police misconduct lawsuits – have turned down their case because police alleged Alvarez shot first. Reached by phone, McWhirter confirmed that he declined to take the Alvarez family’s case after viewing news reports that recounted the police narrative that Alvarez shot Estrella.

“I can tell you that I did a preliminary review of the case and decided not to take it,” McWhirter said.

Without someone to shepherd them through the process – where to get information, how to apply pressure to those who have it – the Alvarez family feels stuck. Every day is tainted by Sergio’s absence.

Destiny still speaks to him “as if he were still here.” Sergio was always playing music, and Isla has noticed how silent the house is without him.

“Every time my dad would smile, it would light up the room,” she said. “When he passed, it felt so much quieter.”

Sergio’s death has probably been hardest on his mother. She’s the “mayor” of the neighborhood, as her neighbor describes her, a woman who worked at a community nonprofit for 16 years. She helped elderly people clean their homes and held back-to-school drives. She assisted people with traffic tickets, kept the local cemetery tidy and cared for street dogs.

But that cool February day at her home, just a few days before what would have been Sergio’s 49th birthday, Maria looked gut-punched. As she gazed on each picture of her son adorning the poster boards in front of the house, her face vacillated between heartbreak and joy. “Oh my god, mijo,” she mumbled, a crackle of desperation in her voice.

Holding one of her great-granddaughters, tears filled her eyes as she recounted one last memory.

“He’d come in the morning and I could hear his music,” Maria said. “He’d find me and give me a big kiss and pick me up, ask me, ‘Mom, what do you want? Let me go buy you a burrito.’ And he’d be off.”