TJ L’Heureux

Audio By Carbonatix

Suspicion and frustration still linger in Guadalupe, a community that has been a target of the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office’s systematic racial profiling. Residents aired their concerns during a town hall last week.

On Oct. 19, a monitoring team selected to oversee court-ordered changes at the long-troubled sheriff’s office hosted a meeting at a local elementary school. The small town, with a largely Latino and Yaqui population, sits between Phoenix and Tempe. A dozen or so sheriff’s office officials also attended, although they mostly gathered at the back of the school auditorium.

It’s been a decade, costing the county nearly $250 million, since a federal judge ordered the agency to change its policies and stop violating the civil rights of brown and Black people. Guadalupe contracts with the sheriff’s office to provide law enforcement for the town.

Last week, the meeting marked a return to the Valley for Robert Warshaw, who was selected to lead the monitoring team in 2014, for the first time since the coronavirus pandemic began.

“I’ve read in the newspapers that we haven’t been here for three years. That’s probably true,” said Warshaw, whose law firm is based in North Carolina. “The realities of COVID made it difficult for us to get here.” He cited “prohibitions for people to travel,” despite domestic air travel restrictions in the U.S. being lifted in 2021.

Warshaw assured the audience that the monitoring team continued to work virtually, adding that his team “constantly” interacts with the sheriff’s office and parties involved in the case.

But some Guadalupe residents, such as Lisa White, who runs a nonprofit that advocates for children and parents dealing with the criminal justice system, are skeptical of the team. She noted that for the month of July, Warshaw billed the county at a rate of $300 an hour. The monthly bill for the county came to more than $210,000.

“(Warshaw) didn’t talk about how much he is making,” White told Phoenix New Times.

The meeting lasted two hours. Several parties involved in the case spoke, including representatives of Warshaw’s team, the ACLU, the U.S. Department of Justice and the community advisory board established for the case.

Residents had 30 minutes to provide feedback at the end of the meeting.

White didn’t have the chance to speak but said she wanted to know which community members had been contacted to help plan the mandated cultural competency training for sheriff’s office officials. “If you’re really trying to break down racial profiling, you need to come to the people and get their input,” she said. “You need to get to know the community as a whole. Did they do that?”

The court oversight grew out of a traffic stop in September 2007 when sheriff’s deputies arrested Ortega Melendres in Cave Creek. Three months later, he sued Sheriff Joe Arpaio and the case, Melendres v. Arpaio, challenged the sheriff’s office’s practice of targeting and stopping vehicles with Latino people inside based on their race and ethnicity in order to investigate their immigration status.

U.S. District Court Judge G. Murray Snow has issued three orders for the sheriff’s office to change policies for its policing and handling misconduct complaints. Even after Sheriff Paul Penzone replaced Arpaio in 2016, the office has not fully met the court orders, including to stop racially profiling Black and Latino drivers.

Longtime community organizer Salvador Reza criticized the monitoring team for labeling racial profiling by sheriff’s deputies as “disparities.”

TJ L’Heureux

Sheriff’s office still targeting Black, Latino drivers

During the meeting, the monitoring team portrayed its efforts with the sheriff’s office as successful.

“MCSO has made significant progress as it pertains to compliance with the requirements of the orders,” Warshaw said.

The monitoring team said the sheriff’s office is in compliance with all but 19 of the 189 orders from the court. However, many of the remaining orders are significant ones. For instance, the backlog of misconduct cases is still high, with the county sitting on more than 2,000 unresolved cases in June.

“The issue of internal investigations and the amount of time it takes to complete an internal investigation is a very serious issue,” Warshaw said. He added that investigations should not take more than a year.

But the most recent report from the monitoring team, filed in August, noted that there are still racial “disparities” in traffic stops. In other words, the rates that Black and Latino people are pulled over are significantly higher than for white people. The monitoring team said that shows “possible systemic racial bias” in the sheriff’s policing.

Yet the monitoring team’s language in describing problems at the sheriff’s office is causing a rift between it and local residents.

Raul Piña – a member of the Community Advisory Board, which the court created to provide public input and oversight – said he was angry that the term “racial profiling” was seldom used during the meeting in favor of the term “disparities.”

“You can do the low-hanging fruit. You have to write a policy manual, then you have to train on the policy. Those are easier to do,” Piña told New Times. “But at the core of this thing is racial profiling. For the seven years that I’ve been working on this, nobody at MCSO, including (Sheriff Paul) Penzone, has ever said, ‘We have a racial profiling problem.’ They’ve never acknowledged it.”

Piña is not the only community member befuddled and alarmed by the frequent use of the term “disparities.”

“They did all the writing, but the issue was racial profiling. They don’t say racial profiling anymore,” said Salvador Reza, a longtime community organizer. “I don’t even know how to pronounce what they are saying.”

In 2010, Arpaio had Reza arrested in a case that was quickly thrown out by county prosecutors.

Maricopa County Sheriff Paul Penzone announced Oct. 2 that he would step down in January and not run for reelection.

File photo by O’Hara Shipe

A new sheriff to take on the case

Though the initial court orders were issued while Arpaio helmed the sheriff’s office, Penzone inherited the issues that plagued the agency.

On Oct. 2, Penzone announced that he would step down in January and not run for reelection, devoting much of a press conference to bitterly lamenting the court’s oversight of the sheriff’s office.

“I’ll be damned if I’ll do three terms under federal court oversight for a debt I never incurred and not be given the chance to serve this community in the manner that I could if you take the other hand from being tied around my back,” Penzone said.

The Maricopa County Board of Supervisors will appoint an interim sheriff when Penzone leaves office to serve until a new one is elected in November 2024.

David Myers, a Guadalupe resident and former Arizona State University professor, said that although Penzone has more common sense than Arpaio did, he did not change the hostile law enforcement style of the sheriff’s office.

“They both practice a confrontational style of law enforcement rather than a cooperative style. Confrontational enforcement is based on evoking fear in the subjects,” Myers said. “In Guadalupe, these are the young adult male Hispanic Yaquis.”

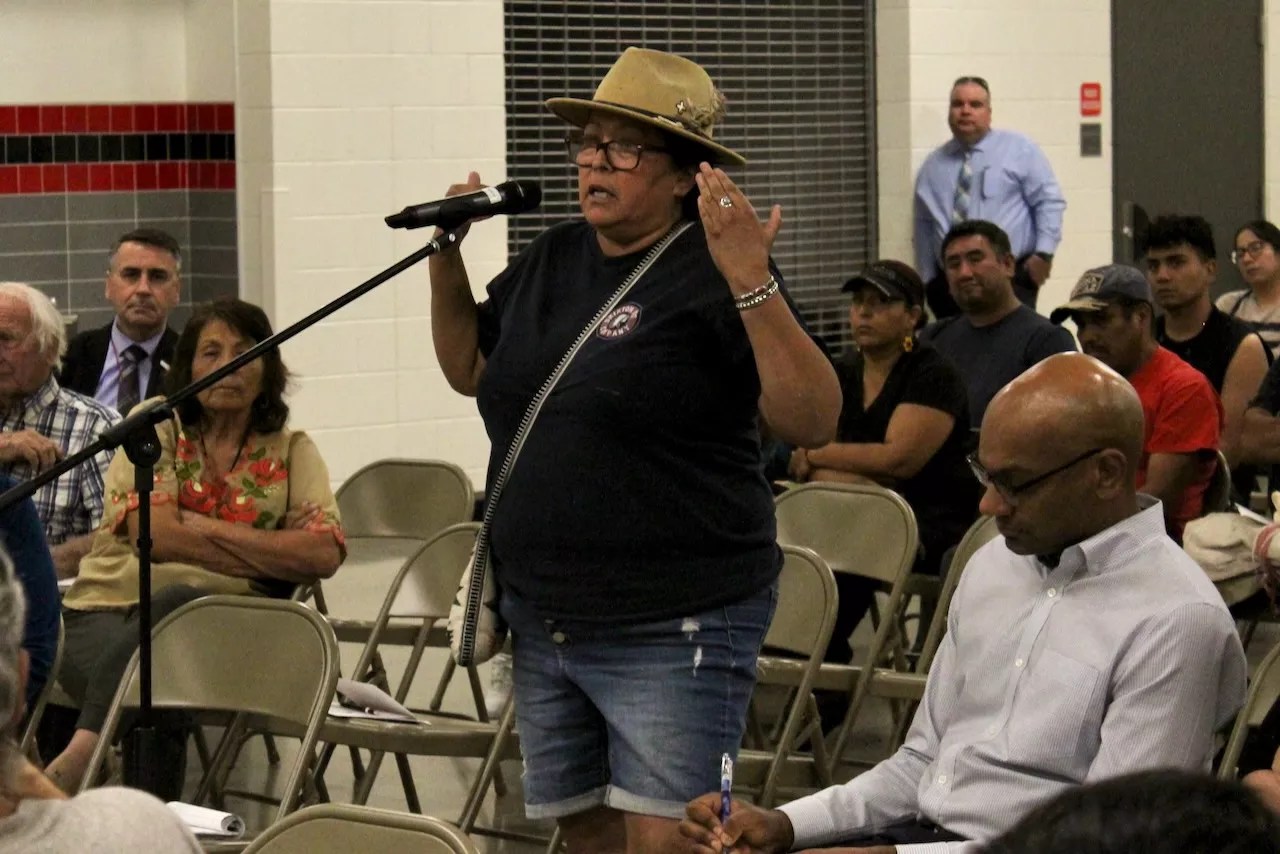

Jewel Valenzuela, an elementary school teacher for 17 years, spoke at the meeting about the trauma the community has experienced at the hands of the sheriff’s office. She told stories about children shaking when they saw law enforcement officers, a tank rolling through the community’s streets and drones chasing people having mental health crises.

“I stayed in this community anyway because these are our families and they are my people,” Valenzuela said. “If they (the sheriff’s office) want to build community, there are ways to do it. But they’re not doing it.”

The monitoring team outlined some of its efforts to investigate law enforcement officers. The team has spent time studying policing patterns of deputies and has had interventions with 17 who were flagged for potential bias. According to the monitors, none have been flagged a second time.

In addition, the monitoring team provided key statistics about biased policing complaints from Hispanic people. According to its data, 566 complaints have been filed since June 2016. Of those, 105 alleged bias.

In 10 cases, the team found bias but said it did not have data to present on what kind of punishment the officers received.

Jewel Valenzuela, an elementary school teacher for 17 years, spoke at the Oct. 19 meeting about the trauma Guadalupe has experienced at the hands of the sheriff’s office.

TJ L’Heureux