Zachary Balber/Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Audio By Carbonatix

Current Phoenix Art Museum exhibition “Charles Gaines: 1992-2003” takes viewers on an often visceral journey, exploring race, class and climate change through imagery that challenges our sense of the status quo.

Charles Gaines, one of the only African-American artists working with conceptualism in the 1970s, is still creating work today that feels fresh and urgent to our present moment.

Incorporating painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, sound and video, Gaines’ work both challenges and reveals systems around us, whether those are the systemic oppression of marginalized peoples, or the beautifully interconnected and supportive roots systems of trees and the natural world.

This exhibition, on view through March 9, examines Gaines’ work over 30 years and includes an engaging and dramatic array of works, from large-scale vibrantly colorful grids of desert landscapes to a diorama installation of a plane crashing into an American city in real time.

Through both familiar and shocking imagery, as well as word collages that incorporate texts from sources such as the Black Panther Party, feminist Riot Grrrl era news articles, interviews with hip hop group N.W.A and historical liberation texts, Gaines’ work encourages viewers to examine their own lived experiences and place in history.

Phoenix New Times spoke with lead curator on the exhibit, Olga Viso, on why Gaines’ work fit perfectly into the Arizona landscape, how trees became a powerful subject of resilience, liberation and social justice movements throughout time and how Gaines invites viewers to see the world around them in new ways.

Charles Gaines, “Numbers and Trees: Arizona Series 1, Tree #3, Agua Caliente,” 2023.

Keith Lubow/Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Phoenix New Times: What about Gaines’ work, specifically his artworks of cottonwood trees and familiar desert landscapes resonate with Arizona and make this show relevant to the desert?

Olga Viso: The whole idea of doing the exhibition came about because Charles was invited to do artwork for the Barrow Neurological Institute’s collection focusing on art as healing. They wanted to create a healing creative environment in the institute for people coming in with brain injuries and serious trauma, to have art be the anchor in people’s healing process.

Cottonwoods exist primarily in Arizona, and he was looking for old-growth trees he could isolate in the landscape. In the barren landscape, their resilience was fascinating. I called a plant physiologist at the Desert Botanical Garden, and we found out that cottonwoods had a deep connection to Indigenous cultures and are a keystone species that support all sorts of bird and animal life.

Charles is not necessarily telling people what to think, or making a comment on the environment. He is creating a platform for audiences to think about what they are looking at, what it means and what are the stories they are bringing from their own context.

So living here, visiting here or growing up here and being in the landscape, he wants people to bring their experiences to his work. So the tree, which seems like a benign, apolitical image, can become an entry point for us to think about systems around us and begin to see them, and question them.

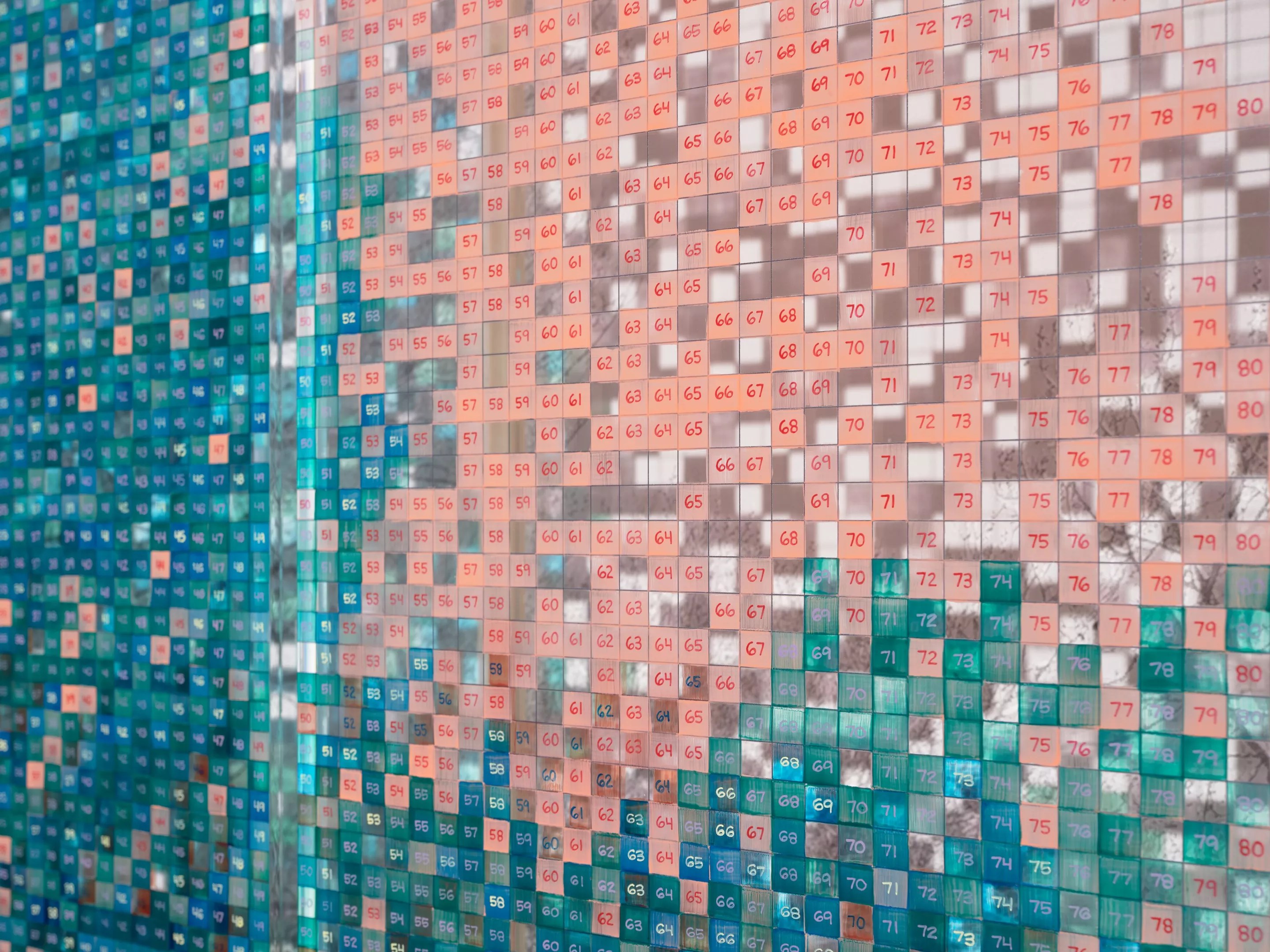

Charles Gaines, “Numbers and Trees: Arizona Series 1, Tree #4,

Tonto,” 2023 (detail).

Keith Lubow/Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

The exhibit examines 30 years of Gaines’ artwork, and gives viewers a dramatic sense of scope.

It’s a big moment. Charles just turned 80 and is finally getting the recognition he deserves. He taught at UCLA for over 30 years, and just retired to focus full time on his art practice. He’s influenced several generations of highly recognized artists from Mark Bradford to Henry Taylor. Charles has not been part of the canon of the art world until recently, and he deserves to be.

Apart from some of the more challenging themes his artwork asks us to think about, there are also just incredibly aesthetically engaging and beautiful pieces that people get mesmerized. Charles has been making images of isolated trees as a powerful symbol throughout his practice since the 1970s.

He’s worked with pecan trees, which were part of the landscape of his childhood in the South, where he grew up near a former plantation, and loaded with histories of the South. He’s done walnut trees, palm trees – all trees that have an association with place or cultural histories.

Installation view of “Charles Gaines: 1992-2023,” 2024.

Zachary Balber/Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

There is a sense of time throughout the exhibit. Some pieces physically move and are on timers, there are clocks worked into some pieces and you get a sense of impending doom and climate catastrophe. There are also portrait pieces that highlight figures of progress throughout time.

That’s lovely, I don’t think anyone has written about that. I really see that sense of time in one of my favorite pieces of the show, the “Skybox” piece, which is a room in the dark where four liberatory texts are illuminated, turning them into almost a visual cosmos, this timeless thing.

And then with the identity portraits that move from Aristotle to bell hooks, it makes me feel like some of these writings, philosophies and thinkers sort of cycle in and out of our consciousness throughout time, from generation to generation.

What I felt in “Skybox” in such a poetic way, is that these marginalized voices who cross generations and time, have their moment of visibility, or they get built upon and reimagined, or discounted and then resurface.

Putting these texts in a museum environment that may not always be in the mainstream, he invites us to look at them in a more open, objective context.

Installation view of “Charles Gaines: 1992-2023,” 2024.

Charles Darr

Trees outlive us humans, they witness and see more perspective than we do. I also felt a sense of paradoxical forces in the exhibit, so there was smog and encroaching disasters. You also have people on the other side pushing for progress, beauty and to understand our landscapes and connection to the earth and each other.

For me, installing the show before the election and reading the texts like the Black Panther Party Manifesto was so powerful. They still felt so present, like they could have been written today. We have texts included from the 1600s in England talking about the rights of the working class and struggling for labor rights. To see those ideas connected centuries across time is incredible.

As part of Charles’s practice, he says that often his intention is to put two things together that may seem unrelated and invite us to think about: What are their relationships? This says a lot about our world, and also about ourselves and these histories we may not know about or which may not have been taught. So you can engage the work on this deep philosophical level, or a purely visual level, or a deeply personal one or a level of curiosity and learning.

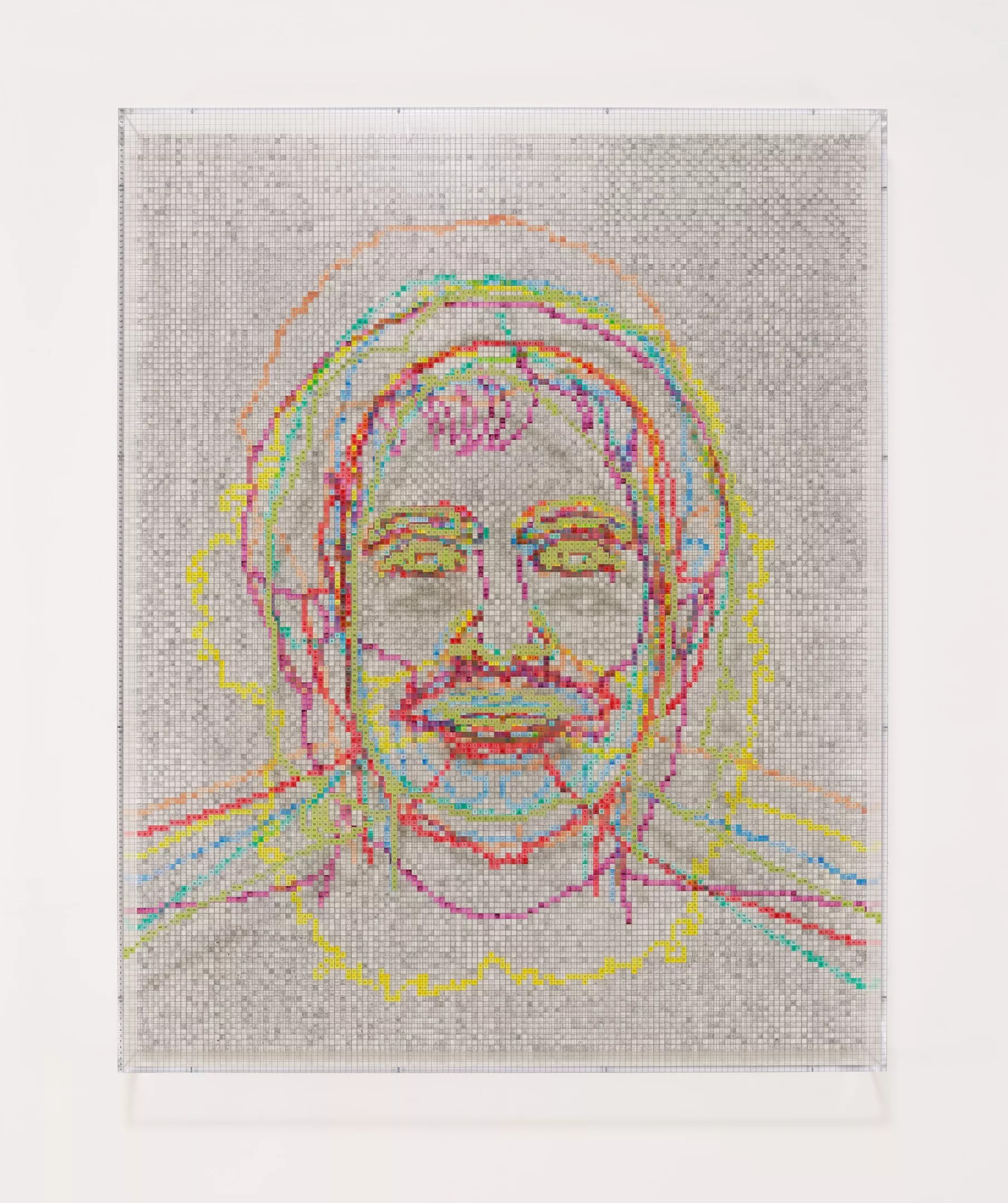

Charles Gaines, “Faces 1: Identity Politics, #7, Dolores Huerta,” 2018.

Charles Darr

The work is meant to be ingested and taken through our own perspectives, which affirms a call to action in our lives. Thinking about what changes we may want to see in our own part of the timeline.

Yes, and we want to encourage our visitors to privilege their own experiences and stories while they are viewing the work. Sometimes we feel like we have to know what the artist meant or what they want us to see. But Charles debunks that – he wants the viewer to take ownership and value their own perspective and lived experiences.