New Times photo illustration

Audio By Carbonatix

The 18,000 Valley residents who gathered at Compton Terrace in Chandler on July 18, 1991, put up with all kinds of headaches. The heat was relentless. Shade was scarce. The lines for the porta-potties stretched interminably. The smell coming from them was even worse. The now-demolished outdoor venue was hosting the launch of the inaugural Lollapalooza, the groundbreaking touring alternative music festival co-created by Jane’s Addiction frontman Perry Farrell.

Born from a desire to do “something amazing” with what was ostensibly Jane’s Addiction’s farewell tour (the band was on the verge of its first breakup), Lollapalooza was an ambitious blend of counterculture, activism, and music. Headlined by Jane’s Addiction, the lineup was eclectic and drew from multiple genres: industrial rockers Nine Inch Nails, Ice-T’s thrash-metal act Body Count, post-punk band Siouxsie and the Banshees, funk-metal group Living Colour, Henry Rollins’ hard-rock crew, and psychedelic noise-rock misfits Butthole Surfers. And it would all debut in Phoenix.

Farrell had uncanny timing. Lollapalooza hit just as alternative music was crossing over into the mainstream. Now-defunct local AM alternative station KUKQ was nearing the peak of its popularity. The festival’s debut in Phoenix drew from all corners of the underground and fringe. Punks and rivetheads. Skaters and hippies. Goths and Rastas. MTV and Rolling Stone were both in attendance.

The same scene played out in 20 other cities across North America that summer. Over the next few years, Lollapalooza revolutionized the music industry, blueprinted the touring festival concept, transformed into a cultural touchstone, and helped define the ’90s. These days, it’s a multimillion-dollar destination festival in Chicago that attracts an estimated 400,000 people.

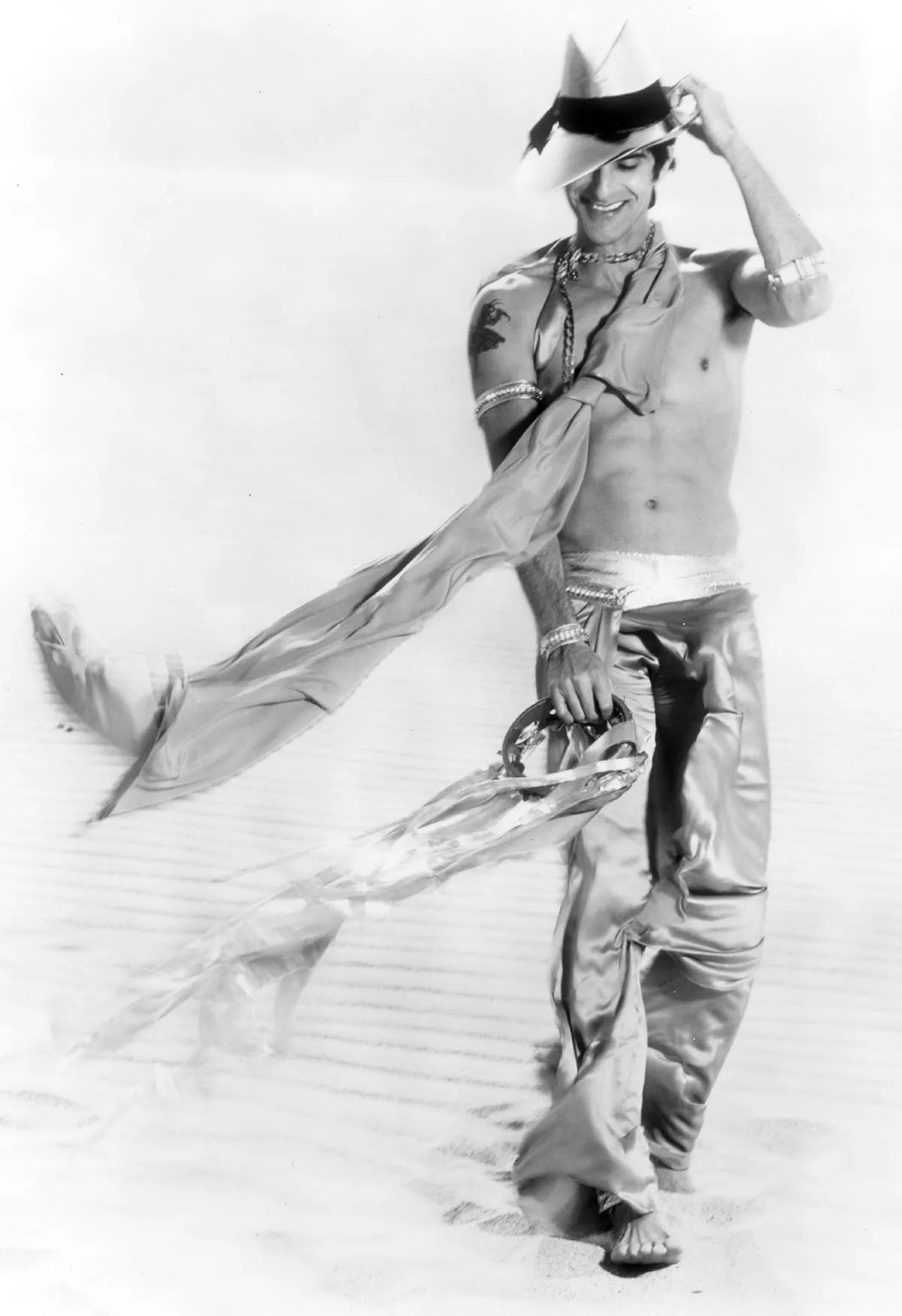

Lollapalooza mastermind and Jane

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

How did this cultural juggernaut end up starting in Phoenix, a city not known for being early adopters of anything? Promoter Danny Zelisko says it was due to his connections with Farrell, as well as the Valley being a testbed – a market where festival organizers could work out the kinks before heading to bigger cities on the 20-city tour.

There were definitely some issues. Nine Inch Nails’ gear malfunctioned in the 110-degree heat. Farrell and Dave Navarro brawled onstage during the headlining set. The crowd battled a scorching sun, long lines, and dust from the nonstop mosh pits. But it was worth it, says Tempe resident Sara Kalish, who attended with her “punker and mod friends.”

“It was hot, it took me an hour to drive to [Compton Terrace], and my car almost overheated on the way to the show, but I had to be there,” Kalish says. “Everyone was talking about it before the show. We were like, ‘What’s Lollapalooza?'”

She wasn’t disappointed.

“It was a really amazing time. I still have my Lollapalooza t-shirt, pit stains and all,” Kalish says.

She has vivid memories of the day – 30 years ago this week – as do the past and present Valley residents who shared stories with Phoenix New Times for a rock ‘n’ roll rewind of the first-ever Lollapalooza.

In 1990, Jane’s Addiction was rapidly disintegrating due to infighting and burnout after the release of its second studio album, Ritual de lo Habitual. A farewell tour seemed inevitable, but frontman Perry Farrell had bigger ambitions: a diverse lineup of musicians mixed with art, culture, politics, and ideas. Farrell enlisted others to help make his dream tour a reality, including Phoenix concert promoter Danny Zelisko, who discussed the idea with the singer after a Jane’s Addiction show in November 1990 at Celebrity Theatre.

Danny Zelisko, longtime Phoenix concert promoter: I owned Evening Star Productions at the time and promoted a few Jane’s Addiction shows in the late ’80s and early ’90s. We were sitting around having drinks at the Pointe Squaw Peak [now Hilton Phoenix Resort at the Peak] after a show and Perry’s going, “I want to do more than a concert here. I want to have the most incredible collection of artists and culture stuff.” And he ran through this whole list of things he wanted to have on this dream concert tour.

Perry Farrell, Lollapalooza co-founder and Jane’s Addiction frontman: I thought I can take all these different elements of music and art and lifestyle and swirl them together and make something wonderful.

Zelisko: And I really got what he was going for. It just made sense. We started making all these plans.

Tim Hardy

Jonathan L., program director, KUKQ: I had a good relationship with Danny; we talked often, and he said, “I’m going to be putting on a show with Perry called Lollapalooza. Can I get you guys behind it?” I was like, “Absolutely.” We very much wanted to be a part of the show. KUKQ sponsored it. And I believe, as they were whipping this thing together with plans and everything, Danny is the one who got them to bring it to Phoenix.

Zelisko: [Perry] brought it here from our history together and because most tours don’t want to ever open up in a Los Angeles or a big megacity like that because they like to work out the bumps in places that aren’t in such an industry spotlight. So over the years, Phoenix and Tucson have been used many, many times as the debut dates.

Justin Valdivia, drummer and former Phoenix resident: The cultural zeitgeist was right about where it could sustain a tour like that. There was enough interest in [alternative music] in Phoenix to fill a place like Compton Terrace if you got a lineup of bands like Lollapalooza. KUKQ had a lot of success with their concerts and Q-Fests.

Bryan Krol, former Tempe resident: This is back before Nevermind came out and everything got homogenized and slickly packaged by MTV, when the underground and alternative were still this weird amalgamation of different tribes and scenes. I think Perry Farrell wanted to bring them all together under one big tent.

Jonathan L.: We started throwing these shows, Q-Fests and our Birthday Bashes, in ’89 and ’90, and, because of our very loyal listeners, had great crowds. Our two-day Birthday Bash in 1991 had Sisters of Mercy and Front 242. Dave Kendall with MTV came out and featured us on 120 Minutes. People were noticing what was happening in Phoenix at that time with [alternative]. I’m sure Perry was aware of that.

Zelisko: I’d been booking Compton Terrace for [venue owners] Jess Nicks, Stevie Nicks’ dad, and his brother Gene for seven years. It was perfect for Lollapalooza because it was GA, the amphitheater was flat grass in front of the stage, wide open, you could seat 25,000 people easily, and there’s nothing you can wreck so the kids could go crazy. The whole show cost probably around $250,000 altogether for the advertising, all the artists, all the staffing.

Zelisko and Jonathan L. started getting the word out. Local record stores were papered with fliers. Ads ran in Phoenix New Times. Commercials aired on KUKQ. Meanwhile, friends were telling friends about the show.

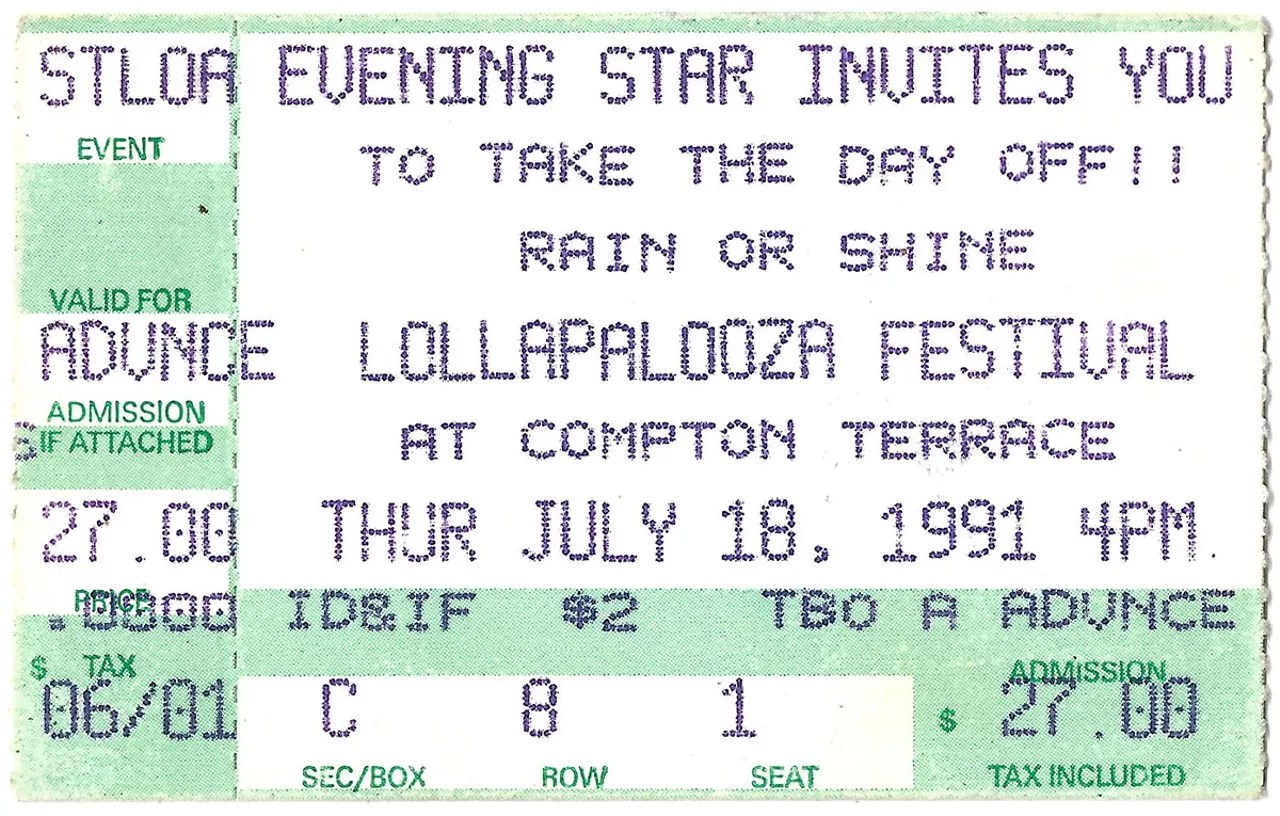

A flyer for the Compton Terrace show.

Tim Hardy

Krol: My friends and I were huge Jane’s Addiction fans and heard they were going to tour in the summer. We were tracking what was happening with the band because the rumor was they were breaking up soon. I think I saw a flier at Zia [Records] for Lollapalooza.

Brent Miles, guitarist and former Valley resident: I probably heard an ad on [KUKQ]. I was stoked when they said Butthole Surfers were [on the lineup]. They still wouldn’t say “butthole” on the radio then, so they called them “B.H. Surfers.”

Stephen Masters, former Phoenix resident: We got reserved seats for like $27, which was a steal even then. I’ve gone to festivals that are over $400 to get into these days.

Valdivia: I was in summer school at Brophy [College Preparatory] and most of the teachers were grad students home from college. They’d play The Pixies, Jane’s Addiction, and all the college radio shit for us and were telling us about Lollapalooza, like “You gotta go, it’s Jane’s!” But I was this stubborn punk kid who hated most electronic rock, and told them, “I don’t want to sit through fucking Nine Inch Nails.” And they kept coaxing me, saying, “Dude, think about all these bands.” My buddy offered to buy my ticket, so I said, “Fuck it. Let’s go.” Funny thing was, I didn’t have to sit through Nine Inch Nails’ set.

Krol: We camped out for tickets outside of Dillard’s the night before they were on sale. When they opened the doors at 7 a.m., everyone rushed in. The ticket counters were in the women’s lingerie department at the time, so there was this mini-riot amongst all the bras and panties to get tickets first.

Zelisko: There was a lot of demand. I think we sold 12,000 [advance tickets].

Arana Wolin, Phoenix resident: Concerts were one of the big social get-togethers, see-and-be-seen things then, so I had to be there. And Lollapalooza was such a big deal because it was so many great bands. It was absolutely the place to be that summer.

It took a while for Lollapalooza’s first-ever crowd to show up at Compton Terrace on July 18, 1991. As with any festival that came after, attendance was sparse when gates opened but grew throughout the afternoon. And it was a varied bunch. What awaited concertgoers was a venue with zero shade from the summer sun, scorching hot metal benches in the reserved section, a large lawn for GA, and amenities that got crowded quickly. Drugs were abundant, at least.

Jonathan L.: I was out there all day with [former KUKQ radio DJ] Mary McCann doing interviews with the artists and calling in live to the station.

Krol: We got there early since we didn’t want to miss Butthole Surfers or Nine Inch Nails. It was a very mixed crowd. There were punks, goths, hippies, misfits, wastoids, and suburban kids who listened to KUPD.

A souvenir Lollapalooza T-shirt.

Sara Kalish

Valdivia: The crowd skewed a bit older. It was more like college-aged/college radio fans, or guys who worked at Zia than high-school kids.

Gene Mustard, former Phoenix resident: I was around graduation age and had just moved to Phoenix from Texas, so I wasn’t used to the heat yet. I remember being out at Lollapalooza going, “Woah. This is intense. This is a different kind of sweating.” I’m asthmatic, so at least it was easier on my lungs.

Farrell: It must have been 110 degrees out there.

Krol: Mid-July in Arizona is just awful. There’s few clouds and the sun’s just bearing down on you. It was really miserable. There was nowhere to hide from it at Compton Terrace, this large grassy dirt bowl filled with heat, sweaty bodies, and misery.

Robden Brethauer, local nightlife promoter: I’d been to concerts in the summer, but never an all-day thing where you’re out from early afternoon until after dark. Compton Terrace had concessions, but it got to where it took forever to get anything to drink.

Brian McDonald, former Phoenix resident: I wasn’t a regular concertgoer and was completely unprepared. I went with no water, no sunscreen, and not a whole lot of money, so I pretty much hit the trifecta of bad decisions. I got to choose between $5 bottles of water and drinking from the fountain, which was a couple of degrees below boiling.

Tim Hardy, musician and Tempe resident: They had water cannons and these cooling stations with showers you could jump under to stay alive. It wasn’t busy earlier in the day, but later on, there were huge lines. You’d get in for a few seconds and people told you to hurry up.

There were also vendors and an “art and issues” tent, born of Farrell’s desire to mix culture and activism at Lollapalooza. It contained booths for activist groups like Amnesty International and local artists like mixed-media sculptor Janet De Berge Lange.

Brethauer: It was different because showing art at a concert was pretty unheard of.

Sara Kalish, Tempe resident: There was this strip of tents by where you walked in. It was groups giving out fliers, people selling patchouli and incense, the T-shirt booth, and, of course, a beer tent.

Krol: Once you looked through the art and the political booths, there really wasn’t much else to do until the music started up.

Paintings and political material weren’t the only things available at the first Lollapalooza show.

Krol: That was the first time I’d been offered drugs. As we were entering, this Wavy Gravy-looking guy rolled by saying, “I got ‘shrooms.” My friend also found a dealer in the crowd with a jug of water with hits of acid on the bottom and took a swig. He was pretty off for the rest of the day.

Valdivia: From what I could see, there were a lot of tabs on a lot of tongues. A lot of passing of [LSD-laced] SweeTarts and Pez.

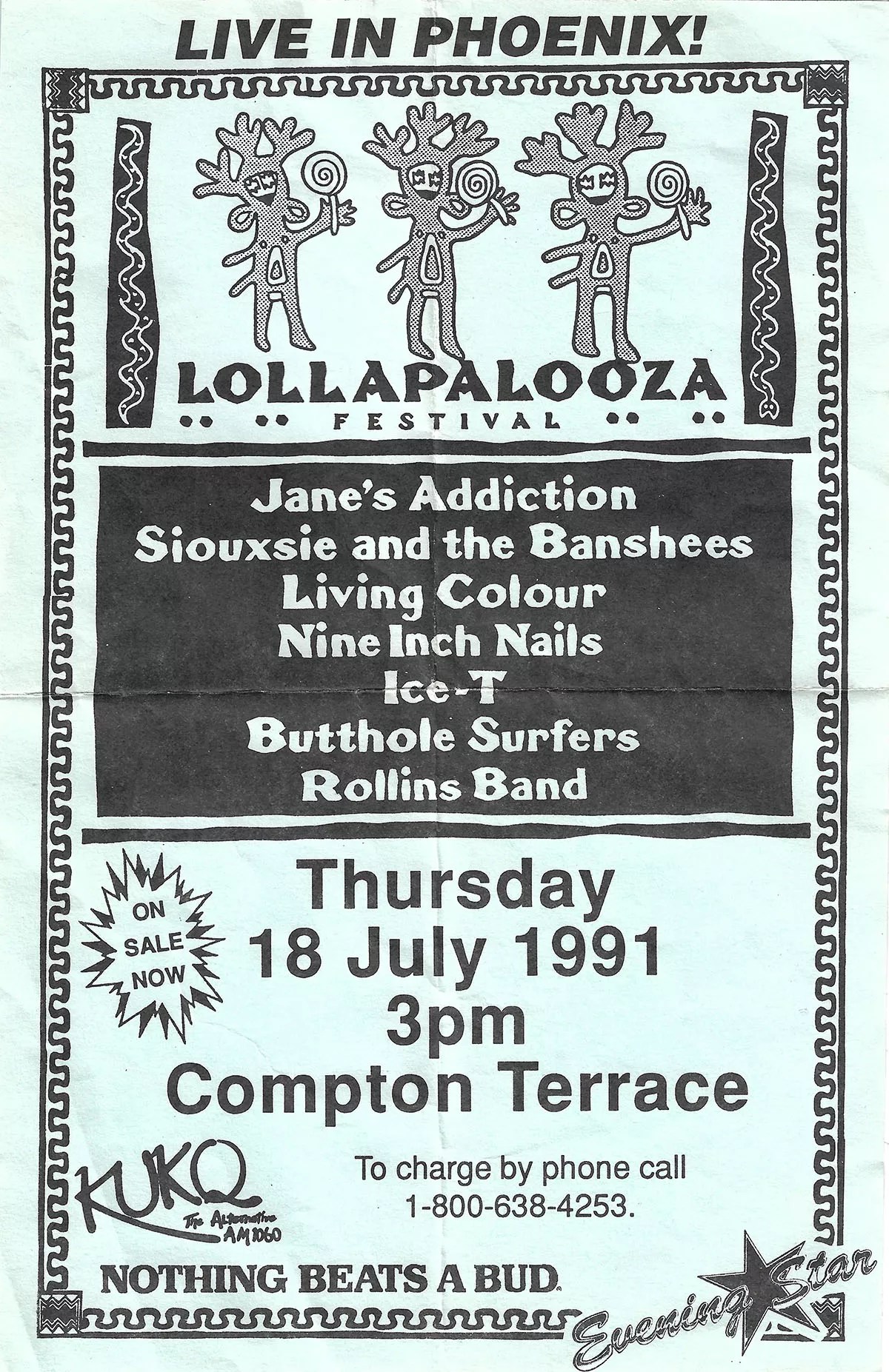

Henry Rollins performs with Rollins Band in the early ’90s.

Rollins Band had the distinction of being the very first act to ever perform at a Lollapalooza when they opened the show at Compton Terrace.

Krol: I’d never seen Henry Rollins before. He went all out like he’s famous for doing, just being really Rollins-like with his shirt off and all his veins popping out. It was almost like he was saying “Fuck you!” to the heat.

Sal Caputo, former Arizona Republic pop music writer: I talked to Rollins before the show for a preview [article] and he said something like, “I like a challenge. I reckon it’ll be 106 [degrees] on the stage, that’ll be wonderful.” And he lived up to it. He was a great opener. He really did his best to rouse everybody up. People were crowding in front of him like it was a Black Flag show.

Krol: The pit started as soon as Rollins hit the stage. It wasn’t big at first, because there weren’t a lot of people there yet, but it got larger throughout the day.

Kalish: We were on the lawn, and that’s where all the action was. People were moshing next to the stage, but more pits were in the dirt areas in the back where the tents were. Because it was so hot you couldn’t sit, not that you’d want to. Those metal benches up front were murder.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, the temperatures were getting to some of the performers.

Chris Cuffaro, tour photographer: Everybody backstage was in a bad mood and pissed off. The heat was just nasty. It was just too damned hot.

Miles: When Rollins was playing, Vernon Reid from Living Colour came out and sat near us and complained about the heat.

Charlie Levy, co-owner, Crescent Ballroom and Valley Bar: I was going to ASU and helping out Evening Star and they asked me to help with Lollapalooza. Danny gave me 10 large Lollapalooza posters and had me get every artist to sign them. I grabbed an extra one for myself and went into the dressing rooms. What a fun job. Perry Farrell was a bit of a smart-ass but friendly enough. Henry Rollins was sweet and wrote a really nice note on my poster. Ice-T was so mean that he signed 10 and when he got to mine, I said, “Don’t sign the last one,” because I was so mad at him I didn’t want his autograph. I also hung out with the Butthole Surfers for a while. I was this young, stupid kid who faded into the background.

Gibby Haynes, vocalist, Butthole Surfers: It was chaos. It was hot. It was flat. It was sandy. Not an inch of wind in the house. We had a practice set the night before and it was chaos. And finally, the day arrived for the very first Lollapalooza show, a moment of glory in retrospect. However, at the time, it was chaos.

Miles: Butthole Surfers was good but it’s more of a small club band, so playing in the daytime really did absolutely nothing for them.

Bill Collins, Chandler resident: [Butthole Surfers frontman] Gibby [Haynes] got up there screaming through his megaphone into the mic and throwing a wall of psychedelia at the audience. They were like a beautiful bad acid trip: bizarre loops, sounds, and a cacophony of noise. You either loved them or hated them.

Ice-T:

Moviepix/Getty Images

Ice-T followed Butthole Surfers and was anything but polarizing. After rapping for half the set, he brought out his newly formed metal project, Body Count. It embodied the festival’s M.O. of erasing genre boundaries and was embraced by the largely white, suburban crowd.

Caputo: I remember Ice-T telling the crowd something about “rock isn’t a black thing or a white thing, just a music thing.”

Mustard: I loved Ice-T already, but wasn’t aware of Body Count. So when he came out with the band and started doing thrash metal, I was standing there with my jaw open. They sounded like Suicidal Tendencies or something.

Valdivia: The cultural significance of Body Count playing Lollapalooza was huge. It awakened some people to [Ice-T] and that a black rapper could play hard rock, but it felt a little self-congratulatory with all those white kids like, “Yeah, fuck the cops. We understand your plight.” Yeah, you truly don’t.

Nine Inch Nails’ set was the most attention-grabbing performance of the afternoon for all the wrong reasons. It was also the shortest. The scorching heat caused their sequencers to flatline two songs in, resulting in frontman Trent Reznor going apeshit and flipping over amps and mic stands before storming offstage. He later joked backstage with MTV News about being “officially the first casualty of the Lollapalooza tour.” NIN’s fans, the bulk of the crowd at that point, weren’t laughing.

Hardy: I was excited for the set, my girlfriend was excited for the set. After the previous band, we were trying to hit the bathrooms and the showers and heard the opening of “Terrible Lie” and ran back to our seats. Then everything went south.

Krol: I don’t remember anything sounding bad when they started playing. I knew Pretty Hate Machine backwards and forwards and it didn’t sound much different from the record at first.

Miles: Their equipment messed up during a song, so they went into another one. You could hear the music but it started fucking up. Then Trent started going berserk.

Zelisko: Me and Perry were sitting on the steps leading up to the back of the stage at the time and we may have been partaking in a little herb. Then, all of a sudden, boom. From 10 feet away, we watched [Nine Inch Nails] flip out and march offstage. No eye contact.

Brethauer: No one knew what was going on, everyone just thought the heat was too much for him. It didn’t help that it was the hottest part of the day and people were getting fed up.

Kalish: Everybody was pissed off and started booing. People were like “Fuck you, Trent!” or “He’s a pussy, he can’t handle the heat.” At the time, we figured, “Okay, there’s a problem, but he’s going to come back out,” so we waited around, but nothing happened.

Krol: Some guy, maybe the band’s tour manager, came out and said, “We’re really sorry about this, and blah, blah, blah, but keep your ticket stubs because there will be another [Phoenix] show announced soon.” But there wasn’t. Shit happens, but as a consumer, I felt kind of cheated. And now you had another hour-plus to kill in the heat until the next band.

Jonathan L.: I spoke with [then-Nine Inch Nails touring drummer Jeff Ward] backstage and I said, “I understand the frustration and all that, but this is a band a lot of people came to see and it was a big disappointment.” I suggested Trent call me at the station and apologize live on the air, and he did the very next day.

Zelisko: I didn’t want to pay [Nine Inch Nails] at first because they didn’t technically do their show. That’s not my fault you brought gear you didn’t road test and assumed it would work under all conditions. It wasn’t personal. I liked them. We all had beers with Perry in their motorhome before the set. They just didn’t live up to their end of the bargain. But I ended up paying them. It’s 30 years ago now. I’m way over it.

The disappointment over NIN’s meltdown didn’t last. Living Colour was next up and delivered what many in attendance (including then-New Times music writer Robert Baird) called the best set of the night, followed by Siouxsie and the Banshees and Jane’s Addiction.

Krol: Living Colour really stood out since they were directly metal and it was largely an underground/alternative music festival. They were great. They had wireless units on their guitars and whenever they switched guitars they’d throw them to the guitar tech on the side of the stage. It was pretty cool.

Brethauer: Hearing [guitarist] Vernon Reid rip into those riffs from “Cult of Personality” over the sound system was amazing.

Hardy: I’d never seen anything like them before. I remember being really impressed by this very progressive metal band. At the time, the genre was nothing but white dudes, so it was really great to see people of color absolutely killing it. I was blown away by their musicality and technical skills.

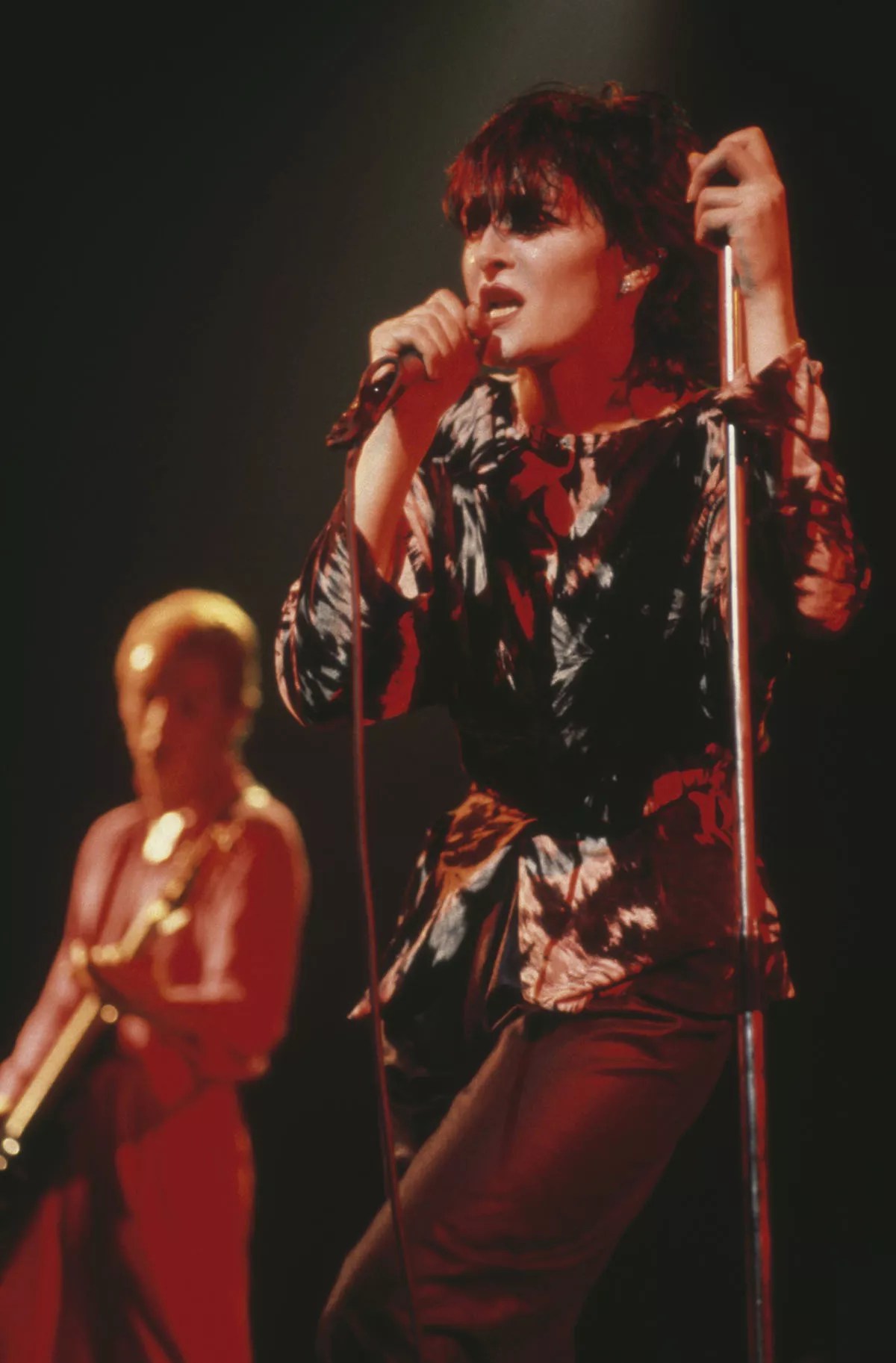

Siouxsie Sioux, circa 1990.

Redferns/Getty Images

Masters: Ice-T went into the crowd when Living Colour played and joined one of the mosh pits during “Cult of Personality” and a few of their other songs. He was really going at it and people were saying afterward, “Did you see Ice-T in the pit?”

Caputo: My impression was that Siouxsie Sioux got the most enthusiastic response from the crowd, but that might’ve been because the sun was going down and people were getting their energy back after the heat.

Wolin: I dropped acid the night before [and] got no sleep, so I already wasn’t in great shape by the time I got there. The guy I was dating broke up with me in the middle of Living Colour. I begged, borrowed, or stole enough money to get a bottle of water, which was the extent of what I ate or drank all day. I passed out on the lawn just when Siouxsie and the Banshees were making their way onstage and didn’t wake up until people were applauding and screaming the end of Jane’s Addiction. No one messed with me, though.

Brethauer: It was still light out, but, by then, the sun had gotten low enough to where the stage was blocking it and everyone was grateful. I thought it was weird seeing Siouxsie Sioux, the queen of goth, in the daylight. [Siouxsie and the Banshees drummer] Budgie was having fun and seemed really into the heat, but I think she was having a hard time with it.

Krol: She was in the middle of her glamming-it-up [phase] when “Kiss Them For Me,” came out. So she had all the dresses and whatnot. I remember Siouxsie Sioux came onstage and said she could smell her brains cooking.

McDonald: Siouxsie had one of her better performances. They were doing the songs I liked; some classic, some new. I pretty much had heatstroke and bugged out after Siouxsie. People were excited to see Jane’s Addiction. I was excited to be leaving and avoid all the traffic.

Brethauer: Getting out of Compton Terrace after any show was always a nightmare with hours of bumper-to-bumper [traffic].

Kimber Lanning, owner, Stinkweeds Records: When I heard about Lollapalooza, my thought was, “I want to reach that captive audience.” I couldn’t afford to advertise at the event, but I could reach people while they’re stuck in traffic trying to get home. I went to Goodwill, bought two giant white sheets and a can of black paint, and painted a sign with something like “Stinkweeds: The Best in Underground Music” and went to the overpass on Baseline Road and hung that puppy off the side. I got a lot of honks and waves from people coming back from the show.

Krol: The crowd was at its biggest for Jane’s [Addiction], but they were disappointing; just sloppy and antagonistic. You could tell Perry wanted to agitate the crowd. During the set, he was chasing Dave Navarro around and trying to pull off his pants. And Dave got pissed and pushed him away.

Farrell: I was in a testy mood. Dave was sick and wanted to bail. He just didn’t want to play.

Dave Navarro: I was in no shape to perform.

Tom Atencio, former manager of Jane’s Addiction: The tension was unbelievable because the band was ending, [former Jane’s Addiction tour manager Ted Gardner] and I weren’t getting along. Dave was so tender, fresh out of rehab, but we had no fucking concept of keeping people straight … he was flung headlong from rehab, straight into this grueling, vigorous tour.

Eric Avery, former guitarist for Jane’s Addiction: Perry and David got into a fight onstage and it cut short our set. Dave was out of his mind on Valium and shit and one of the two bumped into the other one and the other got upset and so then they started taking runs bumping into each other. Then it turned into literally them entangled falling off the side of the stage fighting.

Krol: I remember Navarro throwing his guitar into the crowd near the end of the set and storming offstage. Security wound up getting his guitar back somehow. During “Oceanside,” he smashed the head of the guitar onto a monitor, tried to finish the song, but his guitar was destroyed. He threw it down and they finished as a three-piece and all kind of wandered off.

Cuffaro: Dave just snapped and threw his guitar into the audience and stormed off, knocking over stacks. Perry walked off after the song was finished and they just started wailing on each other, punching each other out. Ted finally jumped in and broke it up. We didn’t know if they were going to come out for an encore. The crew reset the stuff back up and they came out again and started playing, but then Dave started body-slamming Perry while he was trying to sing. Dave knocked over his stacks again, took his guitar, and launched it into space … again.

Navarro: Ultimately I had to leave during our performance, and I don’t remember who got physical with whom first, but I’ve since apologized to Perry because I feel that I was responsible for shattering something that he’d worked so hard on. The opening night was a rough night for me to behave so irresponsibly.

Miles: It’s funny because Lollapalooza was supposed to be all about bringing the alternative crowd together, but then it started off with all these rock stars getting pissed or fighting.

Krol: It was a rough night for a band that had a history of rough nights.

Jonathan L.: I enjoyed the fact this monumental thing began in Phoenix. It wasn’t Los Angeles; it wasn’t Chicago; it wasn’t New York. They chose to do it in Phoenix. People there at the time got a real treat because they had bragging rights, and they still do today. At least the ones who still remember it. They’ll always have the first Lollapalooza.

Valdivia: Not everyone can say they went to the first frickin’ Lollapalooza, but I can.

Editor’s note: Some quotes have been edited or condensed for clarity. Others originally appeared in the 2009 book Whores: An Oral Biography of Perry Farrell and Jane’s Addiction or on Lollapalooza’s official YouTube channel.