Audio By Carbonatix

Esmé will always remember the day June 26, 1990. People don’t tend to forget when their underpants literally melted due to the heat. The Valley resident was working at Sky Harbor International Airport as a wardrobe artist on a commercial shoot for the now-defunct America West Airlines.

It was a bad afternoon to be out on the tarmac. The temperature was unusually high, even for Phoenix: 120 degrees at 2 p.m. – and rising. The original plan was to film inside the air-conditioned comforts of the terminal, and Esmé had shown up wearing an all-black ensemble: a long, sleeveless black linen dress and sandals. But a last-minute change sent them outside in the blazing heat to shoot ground crews at work.

“I wound up sitting on an apple box on the tarmac for hours and hours watching them film people loading and unloading airplanes,” Esmé says. “It got boring after a while.”

But as the temperature kept rising, things started to get more interesting.

“My sandals were stuck to the tarmac, and I walked right out of them,” Esmé says.

She also began feeling a burning sensation on her inner thighs.

“I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, that really hurts.’ I went to the ladies’ room and the rubber around the leg band in my underwear completely melted. Completely melted. I had to pry it off my legs. I still have scars on my inner thighs to this day.”

The pavement practically got molten on Phoenix’s hottest day.

Sophy Smith

The temperature outside would eventually reach 122 degrees, a record that hasn’t been broken since. It was part of a miserable, weeklong heat wave in Arizona that – in addition to baking everyone’s brains and giving transplants a reason to second-guess their decision to move here – resulted in dozens of hospitalizations and at least three deaths.

Phoenix earned headlines nationwide and was the butt of quips from late-night TV talk show hosts. Valley meteorologists had a field day. Entrepreneurs made a fortune selling commemorative T-shirts within hours. Local utility Salt River Project reported sky-high power usage figures. A lot of people freaked out.

Some Valley residents sheltered at home or stayed inside out of harm’s way, while others refused to let external factors like the heat keep them from having a good time.

As time passed, the events of the day made their way into local lore. “It was all people talked about for weeks,” says Valley native Mick Welsh. “For the rest of that summer, everyone wouldn’t shut up about it.”

More than three decades later – this week marks the 35th anniversary -Phoenicians still share tales, now often on social media, about exploding radiators, melted asphalt, and sunburns from hell that occurred on June 26, 1990. Some are true (people tried frying eggs outside), and others are just hot air (like the oft-repeated myth that Sky Harbor Airport shut down that day).

We’ve rounded up a selection of memories from that day. They include quirky shenanigans, battles of man versus nature, and a few tragedies. Here’s that story, sunburns and all. (Some quotes have been condensed and edited for brevity or clarity.)

6 a.m., 91 Degrees

Phoenix in late June 1990 was in the grip of a week-long heatwave. A large, high-pressure weather system lingering over the Southwest resulted in a string of 110 degree-plus days. On Monday, June 25, the Valley reached a record 120 degrees. It didn’t take long to top.

Doug Mummert, retired Phoenix Fire Department battalion chief: It’d been very hot for a whole week. There were several days where we were breaking records, one after the other. When we hit a record of 120 degrees, we thought that was a big deal.

Nancy Selover, Arizona State climatologist: For eight days, we had this big, strong high-pressure ridge sitting on top of us. Very dry air. No humidity, no clouds, nothing to break up the heat, and very little wind.

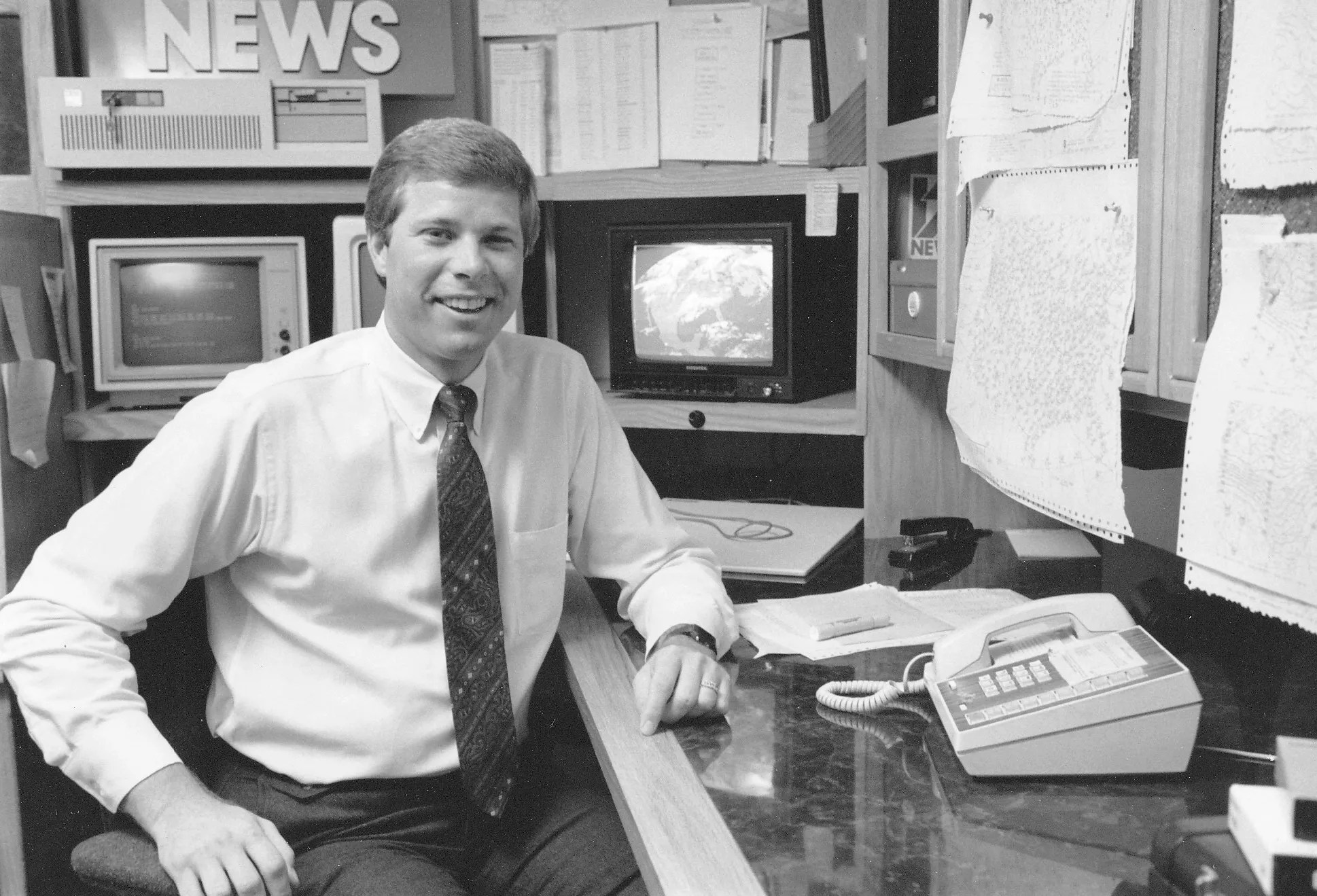

Onetime Channel 12 meteorologist Ed Phillips in the late ’80s/early ’90s.

Ed Phillips

Ed Phillips, former meteorologist, Channel 12 (KPNX-TV): It’s also called a subtropical high, and basically the center of it was right over us, and it just parked there and intensified. Heat can actually build up with time where everything gets a little bit hotter each day.

Selover: We have a heat island situation here. All the pavement, concrete, or metal (absorbs) all the heat and is slower to release back into the air and literally takes all night to get out. And if you keep gaining heat each day, each night gets a little bit warmer, and each morning you’re starting a little bit warmer. It’s cyclical. So at 6 a.m. that morning, it was 91, because that was the most it could cool off since the night and day before were so hot and the pavement soaked everything up. And the temperature kept building from there.

Mick Welsh, former letter carrier: That part of summer, it really doesn’t cool off at night at all. If you lived here, you’d know that. You’d get up and it’d be in the 90s.

Connie Hoy, former Valley resident: I was shooting a commercial for America West (Airlines) at the airport as an (assistant director) or production assistant. Just something for their new livery and some ground crew stuff. Our call was around 5 or 6 a.m. or some ridiculously early time. I was like, “Summer, meh.” It didn’t really feel any different from the previous morning to me.

Welsh: I was a mail carrier for 16 years and worked out of the Sierra Adobe station in north Phoenix that day. Generally, the deeper we were into summer, the earlier we’d start. I remember going to the station at 4 a.m., spending the first two hours sorting mail in a nice air-conditioned building, but I was out on the street at about 6. If you worked as a mail carrier in Phoenix that day, you definitely remember it.

A commemorative T-shirt made by Rich Hazelwood’s company in honor of Phoenix’s hottest day. You can still find ’em on eBay.

9 a.m., 105 Degrees

As the morning progressed, temperatures were rising fast. The thermometer had hit triple digits by mid-morning. By noon, it was 116 degrees. Seeing this, one local entrepreneur got inspired.

Rich Hazelwood, owner, Hazelwoods Enterprises: I own gift shops across the country and a screen-printing company here. We’d get crazy ideas to do T-shirts for things in Phoenix, like the Pope’s visit (in 1987) or the Phoenix Grand Prix. My sales manager, Chuck Zootman, came to me around 9 o’clock that morning and said, “C’mon, we need to print something, this is gonna be a big deal.” Because we’d already hit a record, he had a hunch. I said, “Okay, we need a design.” So, Chuck got with some of the art guys and came up with a thermometer blowing up on the front. We started printing right away.

Chris McLennan, former employee, ARC Traders: We sold Rich beads and necklaces for his shops and he gave us T-shirts as thanks. He had some over that afternoon.

Hazelwood: We had to get them out there that day to strike while the iron was hot. I had them at all my stores, all my competitors’ stores, and on street corners. Boy, I made a lot of money.

Meteorologist Dave Munsey, formerly of FOX-10 (then known as KTSP), with interns atop of the station’s building on June 26, 1990.

Dave Munsey

Dave Munsey, retired meteorologist, FOX 10 (KSAZ-TV): I wrote a book (Munsey Business: 51 Years of Weather, Water Safety and Celebrity Interviews) with an entire chapter about that day. I mention something called the “11 Plus 10 Rule.” You’d take the temperature at 11 a.m., add 10 degrees and you’d pretty much get within a degree or two of what the high would be. So I think I got close.

Bruce Kelly, former radio deejay, Y-95 FM: That morning, my wife and I were up in Pine, but we woke up, the kids were crying, nobody had slept because it was 106 and we had no AC. The Dude Fire north of Payson was 3 miles from our house. We were like, “We gotta get the fuck outta here.” We were back (in Phoenix) by noon and ran right smack into the heat. It seemed like everybody was hiding somewhere, social distancing. In Arizona, that’s called the summer.

Welsh: I remember no one was on the street. No kids playing, no dogs, no one coming outside to greet me. I also kept burning my hand on those metal mailboxes, grabbing onto a piece of iron that’s been baking in the sun all day. We had at least two people who our managers had to go and relieve because they’d passed out in someone’s front yard.

Jerry Bradley, Phoenix resident: I used to be a city of Phoenix inspector for streets and construction. We were paving Thomas Road and I was standing in between a dozen trucks filled with 300-degree asphalt and all the rollers and pavers they were using. It got to the point where I’d gone through a gallon and a half of water and just kept on moving.

Peter Guercio, Queen Creek resident: I went with friends to Canyon Lake at 10 o’clock to go water skiing, and anywhere you touched metal on the boat, it was fire. So kept rotating positions: one guy skiing, one guy on the back and one driving. And we’d ski for really short stints, like five or 10 minutes. Everything was hot, even the water.

Patrick Thielbar, Phoenix Zoo employee: There used to be an outdoor basketball court in the back of the zoo by our employee lounge. We’d usually play every day (as) a lunchtime thing. We did that day, too; the heat didn’t stop us. Kind of like bragging rights, to say you played in that weather. But looking back, it probably wasn’t the smartest thing to do.

Bobbie Pendland, HR manager: I worked at a Taco Bell inside Paradise Valley Mall and we were selling more drinks and cold stuff than usual. There was a shaved ice place across the food court and they were doing phenomenal business. The line was ridiculous; I know because I wanted to send someone for one, and it was just too long.

It was hot enough to bake cookies on a car hood.

Sophy Smith

Rob Birmingham, bartender: I lived in Tempe at this wild apartment complex known as Desert Palms. Some asshole parked in my reserved parking spot, so I baked some Toll House cookies on his car hood right around noon. By 4 p.m., the bottoms were pretty cooked. I was kinda hoping that the owner would come out to see me eating one off of his ride.

David Mills, Phoenix resident: I was 15, on my day off from the Dairy Queen over on 19th Street and McDowell Road. They called me in since it was their busiest day ever. The drive-thru was incredibly packed. There was a good 20 to 30 people standing in line at the counter. And everybody was ordering ice cream and Blizzards like crazy. We ran out of cones and dipping chocolate. The worst part was walking there. I was drenched in sweat by the time I got there. It was harsh, but it could’ve been worse. I can’t imagine how many people lost their air conditioning that day.

Samantha Kitts, IT security analyst: I was almost 5 and we lost power in our neighborhood around noon. Even with fans and misters on, it was like 110 degrees inside our house. We went to buy ice and had to drive 30 minutes away because all the grocery stores and Walgreens were out. When we came home, one of our bunny rabbits had died, so we started making ice baths for all our animals. If you can imagine putting a cat in an ice bath, that’s fun. We ended up losing both our rabbits and our guinea pig. You couldn’t really find anywhere to cool off. It was just oppressive.

Josh Roffler, senior curator, Tempe History Museum: I’d just turned 15 and my family moved here from Idaho. We drove down from Flagstaff that day and it kept getting hotter and hotter, like we were arriving on some alien planet that was too close to the sun. Our car didn’t have AC and it was a crushing, stifling heat that made it super-sticky. Our cats started panting badly with their tongues hanging out.

Mummert: On those days when the temperatures are extreme, in excess of 110 (degrees), the (Phoenix Fire Department) sees a big uptick in calls for service for heat-related illnesses. That week, we had dozens of calls when temperatures were exceeding 120. Not only do we have sick people, but in the summer we do have people who die from the heat.

Susan Ernst, Mesa resident: I was taking my kids to a movie in our station wagon (when) I heard an extremely loud “pop.” It sounded like a gunshot, which I thought it was. I pulled off onto a side street, checked my kids to make sure they were okay and saw the driver’s side glass panel in the back had exploded outward. I think it was from the heat buildup and having the air conditioning on high.

Lonnie Smalley, Phoenix resident: I was (driving) with my mom and nieces going down Baseline (Road). We overheated and one of the water lines broke. I ended up having to walk a mile and a half in that heat to a Circle K to call for help while my mom and my nieces stayed with the car. We didn’t have any money on us, so I had to call my dad collect and wait on him to come and get us. I remember the (asphalt patching). It was hot enough that I was sinking into it, like, an inch. I pulled my foot up and it stuck to my shoes. It ruined my shoes.

Munsey: Around 1 o’clock, temperatures just kept going up and up and up. Every 15 minutes, it would shoot up. It was 112, then 116 and when it hit 118, we were in record territory.

Phillips: Salt River Project also had a big day, as I recall.

Scott Harrelson, spokesperson, Salt River Project: On that day, SRP set a new system peak record of 3,373 megawatts.

Larry Crittenden, former spokesperson, Salt River Project: One thing that I remember is that (SRP was) buying excess power we could get from western states. Our traders were on the phone, two or three days in advance, to meet what we knew was going to be really high demand. We’d made arrangements with some bigger customers (to reduce usage). One big manufacturing facility might use as much power as a whole subdivision or more.

But other than that, I don’t recall us having any brownouts or blackouts that directly attributed to the temperature extremes. That’s not to say that we didn’t have run-of-the-mill outages, where maybe a transformer fails and knocks off a few residential customers. It was an interesting couple of days.

An America West Airlines-owned 737 at Sky Harbor Airport in the ’80s.

2 p.m., 122 Degrees

Phoenix officially smashed the heat record at 2:37 p.m. when the mercury reached 122 degrees at Sky Harbor. But that wasn’t the only news coming out of the airport that afternoon.

Terry Goddard, former Mayor of Phoenix: I was running for Arizona governor in a campaign that seemed to go on forever that summer. What I remember most is hearing what was happening at the airport and being intrigued by it.

John Sawyer, former general aviation supervisor, Sky Harbor: It never shut down. Our policy was, we never shut down. In the 30 years I worked there, the only time was 9/11, after the feds said we had to close. Airlines can stop flying, but the airport is always open. That’s the situation that was happening. The issue was just with the airlines (like America West and Southwest). When it got hot that afternoon, their calculations and performance charts didn’t go high enough on older planes for temperatures above 120. What happens is, when the air gets real hot like that day, it gets thin and (pilots) calculate how to get sufficient lift in the thinner air. It’s called density altitude calculations, and it’s done for weight and balance. That tells you how much weight and fuel you can put on the airplane. You have so only much runway, and you have to have enough length to get off the ground.

Bobbie Reid, former ramp manager, America West Airlines: We didn’t have performance stats for the (older) 737s that we had at the time to take off in those temperatures. We knew the airplane could fly and fly safely, but what we call our weight-and-balance sheets and our other paperwork did not run up to 122 degrees. So we had a short period of time where we couldn’t launch anything, but we could land stuff. And it was what today we would call a ground hold until we got a hold of Boeing to figure things out or waited for the temperatures to go down below 120 after 5 or 6 p.m Then, we could take off again.

Sawyer: It’s highly regulated, and there’s documents that they have to do for each flight, and you got to make sure that the aircraft’s going to perform efficiently enough to be safe. And all of that deals with weight and balance and air density and altitude calculations. And they couldn’t complete their paperwork, so they couldn’t go.

Reid: I got interviewed by Univision, standing on the ramp where we park airplanes. It was so hot. I was standing in pumps, a skirt and high heels, sinking into the asphalt while being interviewed.

Hoy: While we were out shooting the America West commercial, (we) put a thermometer on the dolly and it was close to 120. There was no way to describe it other than it was fucking excruciating. A grip pretty much keeled over after lunch, cause he wasn’t doing enough water and Gatorade. Because the planes weren’t taking off, we couldn’t shoot the rest of the day. Everyone canceled and we went home. It was like it was a reverse snow day.

Sandy Mittendorf, Mesa resident: We were at the airport in Calgary that morning, and the temperature was 50 degrees. We flew back, and as we started making our final approach into Phoenix, the captain came on and let us know we’re preparing for landing and said “Welcome to Phoenix. The temperature is 122 degrees.” And everybody shouted out, “No! Turn around! Go back!”

Dave Pratt, longtime local radio deejay: I was getting on a flight to Vancouver for a performance. When my manager dropped me off at the airport, I went inside to check my bags. The lady at the counter told me that flights were canceled due to the heat. I called the convention organizers that had booked me in Canada, and they laughed. They didn’t believe me.

Gavin Rutledge, former co-owner, Casey Moore’s Oyster House: It was big news that the planes weren’t taking off at Sky Harbor Airport … that was the big news of the day. A lot of people were in shock, like “Holy shit, is this town going to be uninhabitable someday?” People were talking about that back in 1990. We knew about global warming then.

Lin Sue Cooney, former reporter/news anchor, Channel 12 (KPNX-TV): As I recall, the newsroom pulled out all the stops to cover (the heat) – including talking to people who were out in the heat working or going about their day. Many were not aware of the record temperature, and, as usual, thought the press was making a mountain out of a molehill. Their take was, “What’s a few more degrees when we’re already incinerating?”

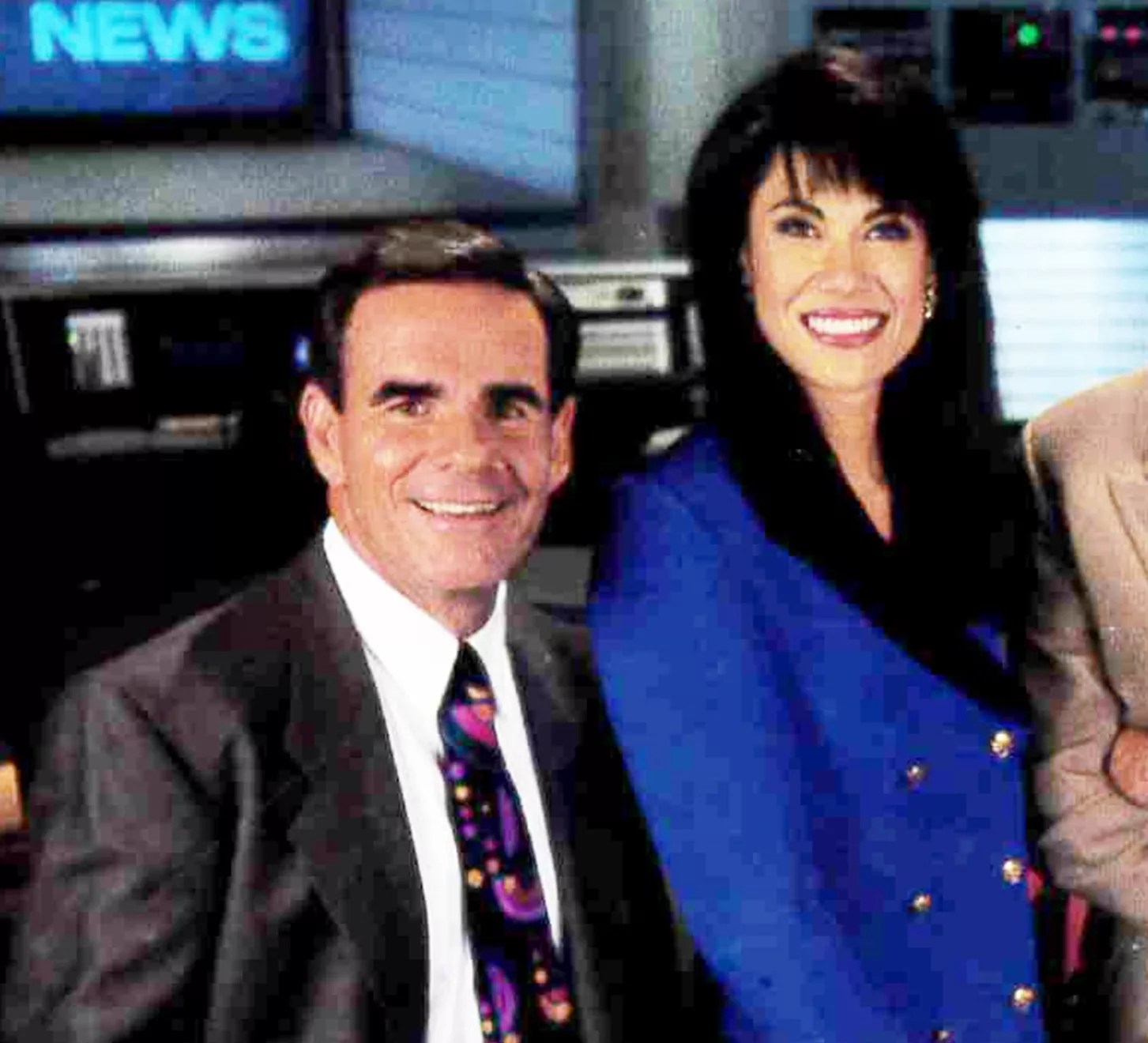

Channel 12 publicity photo featuring former anchors Kent Dana, left, and Lin Sue Cooney.

Lin Sue Cooney

I also remember, to my horror, that all the makeup in my purse melted as I ran around in the heat getting interviews. A bunch of expensive lipstick turning into goo.

Kent Dana, former news anchor, Channel 12 (KPNX-TV): (The heat) quickly became the lead story. It made the decision that day pretty easy because of the overall effect it had on the Valley and what people were doing to deal with it. It was an automatic lead.

Pat McMahon, local actor/broadcaster/entertainer: When I watched the weather that night on the news and those astonishing numbers came on the screen, I’m sure I shouted out an obscenity of some kind.

Munsey: We were planning to do certain things about the high temperatures, and all that went out the window once we hit 122. Other affiliates started calling and wanted a live (segment) with me about it. When winter was severe in Cleveland, they’d call us and want to do a contrast story. I did these all the time, usually on the roof of our building.

On the way up, I got five interns (and) we worked out a bit. The most interesting thing was, after we got off the air, we had 250 phone calls from all around the country and not one question about the weather. That particular day, I had been wearing a pair of leather suspenders, and they were braided. Everyone asked, “Where could I get a pair of suspenders like that?” Not one person asked about the weather.

Bob Boze Bell, Arizona historian/writer/artist: Don’t kid yourself. Our summers are the worst. I’ve been through more than 50 and I can assure you it never gets easier. Here’s my pecking order for Phoenix survival: 95 degrees is a piece of cake. 105 is uncomfortable, but anything over 110 is nuclear. The day it hit, 122 felt like a meltdown. It hurt to breathe. I’m not kidding.

Marshall Trimble, Arizona’s official state historian: I’d been up in the Four Corners area on a field trip with a group of teachers and tour guides from Scottsdale Community College. When I got home that day, the first thing I noticed was the heat had turned my swimming pool a bright greenish-yellow, and I’d loaded it up with chemicals before I’d left.

Carvin Jones, local blues guitarist: I was out working a construction job at the (Union Hills water treatment plant). Man, was it hot. Guys were just passing out and ambulances were coming to take guys away before heatstroke got them. It was crazy. Couple of weeks later, I quit and haven’t worked another job except playing music ever since.

Curtis Grippe, drummer, Dead Hot Workshop: We were roofing these vacant houses along (what would become) the Loop 101 freeway in Scottsdale. One place had running water, so at the end of the day, we hosed off the driveway and laid down in the water because we were just baking.

Mike Gentry, journeyman electrician, Salt River Project: We were putting underground conduit into the trenches at Scottsdale Road and McDowell by the old Ray Korte Chevrolet. The 120 the day before was astounding, then we hit two more degrees. When you’re working outside, there wasn’t much difference between the two temperatures. Both days were absolutely brutal. It wasn’t fun being down in a trench gluing conduit together.

Sitting at a bus stop during Phoenix’s hottest day ever wasn’t much fun.

Sophy Smith

Pendland: Getting home from work that day was torture. At the time, (Taco Bell) uniforms were made from this polyester that didn’t breathe at all. Walking across the blacktop at Paradise Valley Mall was like walking across the surface of the sun and it was even hotter that afternoon. I wound up waiting for the bus for like 45 minutes. By the time I got home, I was an incredible shade of purple.

Sloane Burwell, Phoenix resident: I’d just moved here from NYC and was living at a friend-of-a-friend’s apartment in Tempe. I tried walking over to Mill Avenue to look into some stupid telemarketing job. And my feet were burning up. It never occurred to me the heat would transfer through concrete or my Keds. I discovered some creative ways to walk on the sidewalk.

Chuck Hall, local blues guitarist: I used to run 6 miles every afternoon, even in the middle of summer. I was okay for the first couple miles that day, and then it started wearing me down. All of a sudden, I literally just stopped, got a little chilled, and was like, “I can’t run another step.” All I could do was turn around and walk home. I felt strange all night, and when I picked up my guitar I couldn’t (play). It took a few days to get back to what passes for normal.

Donna Durkalec, Phoenix resident: My rock band Where’s Valentino was supposed to audition for “Star Search” that day. We’d sent a tape in prior to that and they’d set up something at a Tempe studio to see us (live) and talk to us. We were all set up to play but the guy just couldn’t get a plane to Phoenix for some reason. So he never came out and it just never happened.

Sophy Smith

Deborah Reardon, Litchfield Park resident: At the Revco (drugstore) where I was working, one of the outer brick walls was so hot from the sun hitting it on the other side, the makeup hanging on it was starting to melt. Even with the air conditioning on. So we took it all down before it made a mess.

Beatrice Moore, local artist: I remember driving around downtown Phoenix in my vintage 1960 pink Cadillac with my windows down since the air conditioning wasn’t working. It was unbelievably hot and felt like having a heater smacking you in the face full blast.

Danny Zelisko, longtime concert promoter: A musician was visiting our offices that day from out of town and were out of their minds with how hot it was. I demonstrated cooking eggs on some ceramic tiles that had been outside baking in the sun all day. And it literally cooked. Didn’t take long. Those tiles were definitely hotter than 122.

Hans Olson, blues musician: Things just felt off that day. I was with a few guys from the Phoenix Blues Society opening a bank account on Central Avenue in downtown. At that moment, a car blew its radiator at the intersection where we were standing. Then another one blew. I said, “I’m getting the heck outta here. This is too weird.”

Now-defunct Tempe bar and music venue The Sun Club.

Tempe History Museum

8 p.m., 112 Degrees

The sun went down, but Phoenix stayed hot that night. As most residents cooled their heels at home or recovered, others hit the still-smoldering pavement and headed for local bars to drink up, get down and rock out, hot weather be damned.

Michael Vogt, Phoenix resident: It wasn’t much of a very different night for me and the people I know. So it was 110, 120 out? Eh, who cares? After playing tennis at Glendale Community College, we went to (now-defunct bar) Farrah’s on Camelback near 43rd Avenue and drank, danced, the whole thing. There was nothing stopping us. It was pretty full, like Farrah’s normally was in those days. Stayed until 10 p.m. and came home, but by that time we were so lit, we wouldn’t have cared about how hot it was.

Guercio: My band at the time, Local 118, was at (now-defunct Tempe bar) The Sun Club that night. And anybody who played back then knows the place wasn’t air-conditioned, or it never really worked. The Sun Club was notorious for this drummer’s alcove behind the stage, basically a box cut-out with no air circulating. I’m gasping for air back there drumming, and with the stage lights and the lack of oxygen, telling myself, “Oh God, please don’t pass out in the middle of your set.” And (late soundman Nino Notaro) was behind the soundboard in this little cave as well. I remember saying to him as we loaded out, “I was going to pass out up there,’ and he was like, “Dude, how do you think I feel?”

Dana: I’m pretty sure I jumped in the pool after work. That was automatic, because when you sit on the set during a newscast, it’s just hot, and you get home, you don’t necessarily want to take a shower, so it was easier to go jump in the pool. I usually got home about 11 o’clock, and the pool was always nice at that time.

Dana: Whenever we get close, I always hope we don’t break the record. The number’s just stayed in my head all these years.

Selover: Do I think we’re ever going to hit the record again or break it? Yeah, because we’ve gotten close again and again: 119 in 2013 and 2017. I’m only kind of surprised it hasn’t hit 122 again. Sometimes it seems more like a fluke, but I don’t necessarily buy that. I expect we’ll ultimately get to that point again. It hasn’t happened yet, but it will.