Photo by David Rhodes/Illustration by Emma Randall

Audio By Carbonatix

Frequent readers may already be intimately familiar with Long Wong’s. From the early ’80s through its final show on April 3, 2004, the restaurant and venue achieved two things – selling great chicken wings and helping to break big bands like Gin Blossoms and The Pistoleros, among many others. This hole in the wall was the center of the action when the Valley was a hotbed for national rock.

But the value of Long Wong’s goes even deeper still. It’s a reflection of what makes this whole state really vital. Like, the way we grow communities with this shared underdog mentality. Or, how we make due with extreme conditions and iffy resources to make something truly important. Even how the best things here lovingly champion stuff that no one else might care about elsewhere. It’s a chicken wing joint as much as it’s a defining statement for our home, and its significance is often hard to fully encapsulate.

But, on the 20th anniversary of Long Wong’s closing, we’re going to try anyway. Below are interviews with just a fraction of those whose lives were touched by Long Wong’s. Some are staff members and residents, and others are well-known rockers. Either way, each person is a small part of this tale, and living proof of why this place mattered then, now, and will for years to come. While this isn’t a definitive history by any means, these folks still offer vital tales of family, rock ‘n’ roll excess and creativity that captures what made Long Wong’s truly special.

Long Wong’s may be gone, but like a sauce stain on your T-shirt, its mark remains.

Dead Hot Workshop performs at Long Wong’s in 1990.

Tempe History Museum

A place for growing up

Many bands who cut their teeth at Long Wong’s were in their early 20s. Some future A-listers, however, started even younger

David Rhodes, member of Big Finish and American Standard: I was young; probably 13 years old. I would skateboard down to Mill Avenue because my brother (Phillip Rhodes) got out of the Navy in ’85 and he joined the Gin Blossoms as their drummer. And we would go as a family – yes, with my parents – to watch my brother play at Boston’s.

I ran into [singer] Robin Wilson in the bathroom and he had a Bud and was like, ‘Do you want to finish that?’ I said, “Hell yeah, I’m rocking.”

But even those not underage found plenty of wisdom.

Mark Zubia, member of Chimeras/Pistoleros and solo artist: You could go play for good or bad, but at least you were able to take that song that you were writing that afternoon and go perform it that night as opposed to spending a month in the rehearsal shed honing it. It’s like you were thrown into the fire and you get that immediate reaction.

Curtis Grippe, drummer for Dead Hot Workshop and Ghetto Cowgirl: You know, I’ll tell you the truth: We were trying to sound good. And there were those of us bands who could actually pull it off, and who could sound decent, because we figured out guitar volumes and things like that because you’ve got to do it on your own.

Ghetto Cowgirl performs during Long Wong’s final weekend of shows in 2004.

David Rhodes

It helped, of course, that Long Wong’s was open more than some “competitors.”

Grippe: You’d be there at happy hour. You’d be there in the afternoon. You’d go get your gear the next morning.

Bands were never alone in learning to be functioning musicians.

Rhodes: It was Mike Kellums (of Satellite) or (Paul Cardone) that helped us tweak the knobs. Shit, it could have been Zubia for all I know. But you’ll learn those things from the elder statesmen that are kind enough to kind of show you the ropes. That’s what contributed to the overall vibe of the scene. It’s like you’re a part of something that we’re all a part of. It made it the community.

The grungy, iconic, beloved interior of Long Wong’s.

David Rhodes

You can hear it all over

While bands learned on the job, there’s no denying that the awful sound was part of the Long Wong’s charm. It was about embracing those DIY vibes and celebrating the venue for what it was: a chicken joint that threw concerts.

Sara Cina, booker/manager: We didn’t have a sound guy, we didn’t have lights, we didn’t have a PA. There were a couple of speakers and the thing was slapped to the wall. It was the least likely music venue.

Zubia: You could hear flaws and all. So you couldn’t disguise anything. You were either tight, well rehearsed and had your shit together, or you didn’t. You couldn’t hide behind any production, or having any distance, which creates some sort of illusion that the band is better than they are up on stage.

Adam Carter, guitarist for Steppchild: The room sounded awful. There was no lighting there. There was no sound guide. The mixing board was on stage. The bands were controlling the mixer. The mixer only worked at 75% of its ability, maybe. And you know what, if I could, I’d go step back on that stage tomorrow.

Still, bad sound quality had some real upsides.

Grippe: If you can sound good at Long Wong’s, you can sound good anywhere. Except in the cases where you’re at the mercy of a sound guy or something when we started playing bigger venues and touring with like Joan Osborne or Dishwalla or bigger bands.

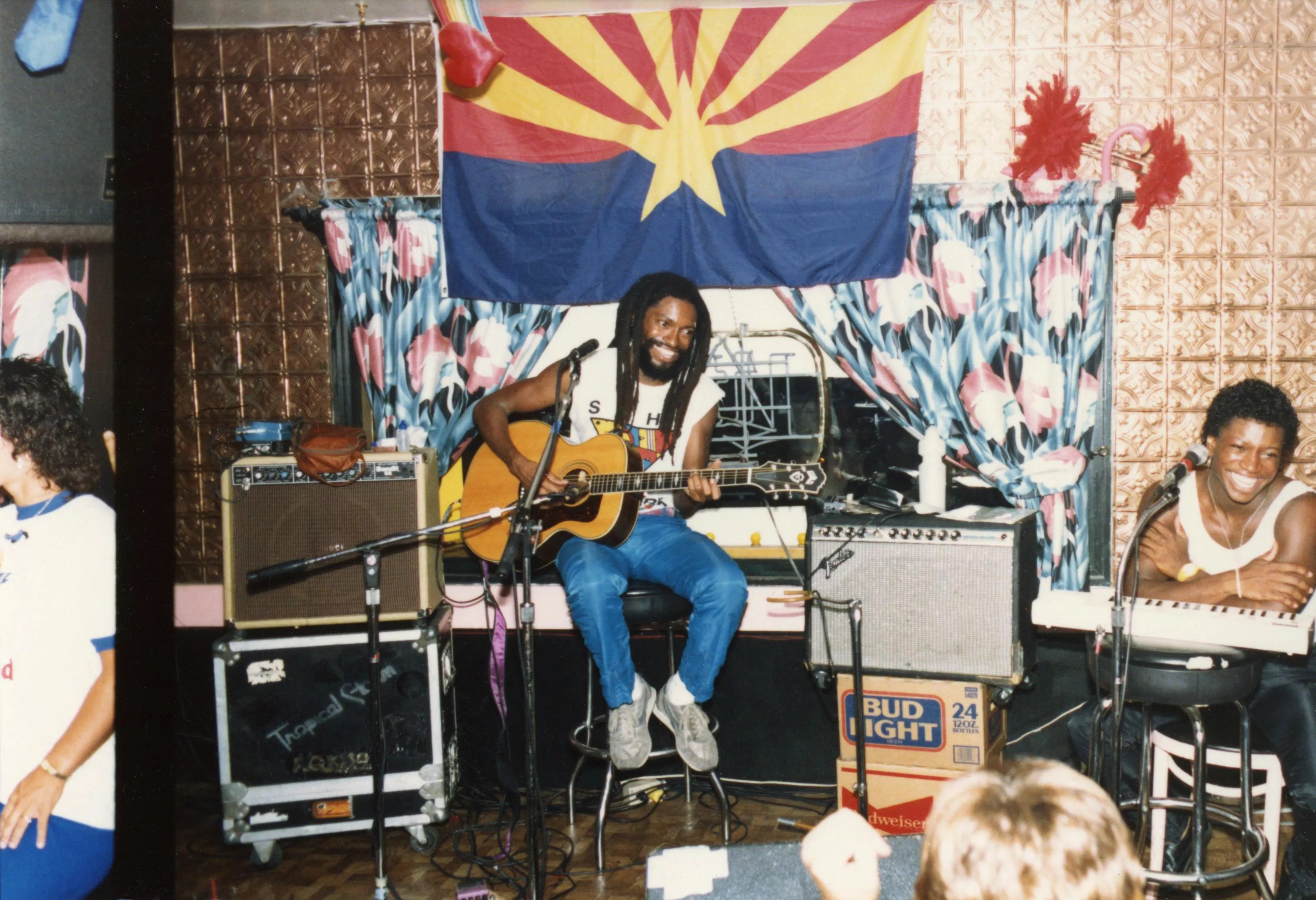

Walt Richardson performs at Long Wong’s in an undated photo.

Tempe History Museum

True to the very roots

It wasn’t just that the sound sucked and people made do. Rather, Long Wong’s was a touch dysfunctional to its core, and everyone embraced that as a badge of honor. It meant they’d all built this place from something weird and broken into something wonderful.

Dave Wolfmeyer, singer/guitarist for Truckers on Speed: There’s maybe three buildings in the whole state that were actually built with music in mind. Everything else is just a restaurant in a strip mall that somewhere a manager or an owner was like, “Oh shit, we need to get butts in seats and people drinking, so let’s do music.” I mean, every fucking room in the state sucks … except the handful of places that were designed for music.

Still, that tight space did have its benefits. If you’re going to a rock show, there’s something to all that close proximity to bands and fans alike.

Carter: That little room got so smoking hot and heated up that most of the time that door was open and all of the time that curtain was open behind the drummer.

But there’s just an energy that this type of restriction brings. I also think that there was a whole component of the audience going, “Hey, I am here seeing this tonight. I am one of the few.” Like, “I got in here to be in the room while this was happening tonight.”

Steppchild performs during Long Wong’s final weekend of concerts in 2004.

David Rhodes

Wolfmeyer: Whenever you’d load your crap off the stage and hang out afterward, you’ll have people coming up and telling you if they like you, which was cool for immediate feedback. Or I guess let you know if you suck right away too and just walk out. Could we have gone into a metal bar and done what we were doing and get the same reaction? Probably not.

Rhodes: Because it’s so small, and there’s no negative space in between people as you’re looking out from the stage. And it amplified the energy. Like, you can’t bottle that shit. People would move in one place, you’re shoving somebody, so somebody else down the bar is moving and feeling your bump.

The “notoriously awful-smelling” bathrooms at Long Wong’s.

David Rhodes

Even some of the, um, less savory elements of Long Wong’s are often viewed in hindsight with a touch of nostalgia bordering on romanticism.

Wolfmeyer: God, there was one stretch where one of their pipes broke under the building. And I mean, it was fucking raw sewage under there, man. It stunk to high hell. And in the middle of monsoon season – that didn’t help anything either. We’re playing and six inches below us is just this cesspool. But that’s fucking rock ‘n’ roll, right?

Bruce Liddil, longtime Tempe resident: A friend of mine lived next door, or two lots over at a motel that became apartments. He called it “stinkin’ drinkin’ because the bathrooms were notoriously awful-smelling. I could pretty much take a deep breath and go in there and do your business and get out as quickly as possible.

Scott Andrews, left, and Mark Zubia of The Pistoleros.

David Rhodes

Something in the water

It wasn’t just lackluster sound quality and poor design choices. So much of what made Long Wong’s feel truly magical were the intangibles.

Grippe: The truth is that within a five-mile radius during the early ’90s, you had 12 major-label bands. There was still this nucleus of national-caliber bands in one area.

There was no denying, of course, that Long Wong’s stood at the center of this ’90s rock “network.”

Rhodes: Long Wong’s was the crown jewel of that scene because they had the most diverse, the most avant-garde, the most cutting-edge and most relevant musicians of anywhere on the block because they’d been doing it for decades before everybody else.

The Zen Lunatics perform during Long Wong’s final weekend of shows in 2004.

David Rhodes

Plus, few other places let bands play almost exactly as they intended.

Chris Hansen Orf, guitarist and country music journalist: Del Montes (a “secret identity” of the Gin Blossoms), I think there was one month there that they played like 18 times there or something.

Grippe: I liked three-hour sets. I sweated my ass off there a couple of times a week for years and years. It felt good to play there. I loved going home after that and just being exhausted and dehydrated. It was the epitome of leaving it on the stage.

Ultimately, though, it was less about the venue itself and those larger “interactions” with Mill and Tempe at large.

Carter: Back then, it was just a free for all. So you would have all of this energy filing out into the street that reciprocated and flowed right back in. And you might have a crowd of people around the door and behind you in the window. You’re playing with all that energy.

The Gin Blossoms onstage at Long Wong’s.

David Rhodes

That Tempe sound

One of the ways that “energy” is seen even today is that Long Wong’s supposedly helped birth the “Tempe sound,” a jangly approach to pop-rock championed by banks like Gin Blossoms.

Rhodes: After the Gin Blossoms had taken off, it was more salient of a concept than it was prior. Because before that, it was just bands making noise. And I remember watching that transition from where everybody and their brother who could freaking hold a guitar was starting a band in the ’90s because of Gin Blossoms.

Grippe: The Gin Blossoms, though, were different. They had a sticker that said, “Gin Blossoms. Tempe, Arizona” when they were on “Late Night With David Letterman.” Robin wore a Dead Hot Workshop shirt. They took us and the Refreshments on tour with them. They actively promoted our town.

As important as the Gin Blossoms were, that whole “Tempe sound” moniker often proved a touch problematic.

Cina: I just hate that term, “Tempe sound.”

I know that there’s people that think about the ’90s and they think about a certain type of music. Even if you think about Seattle, I’m sure there were a bunch of other bands that didn’t sound like what you think Seattle sounded like in the ’90s.

Long Wong’s on Mill: gone, but not forgotten.

David Rhodes

Plenty of other bands deserved the spotlight. Dead Hot Workshop, an often under-appreciated member of that musical community, were regularly touted across these interviews.

Zubia: What about Dead Hot Workshop? When I think of that whole era and all those bands, they’re at the top of the list of the bands that created that.

There were other acts and artists, of course.

Carter: Kevin Daly and Dave Insley from The Trophy Husbands made friends with us and they were like, “You guys are awesome, let’s do a show.” I remember going, “What are we doing playing with a band like this?” But the cool thing was that everybody just embraced good music. They didn’t care what it was, as long as it was good and it was fun.

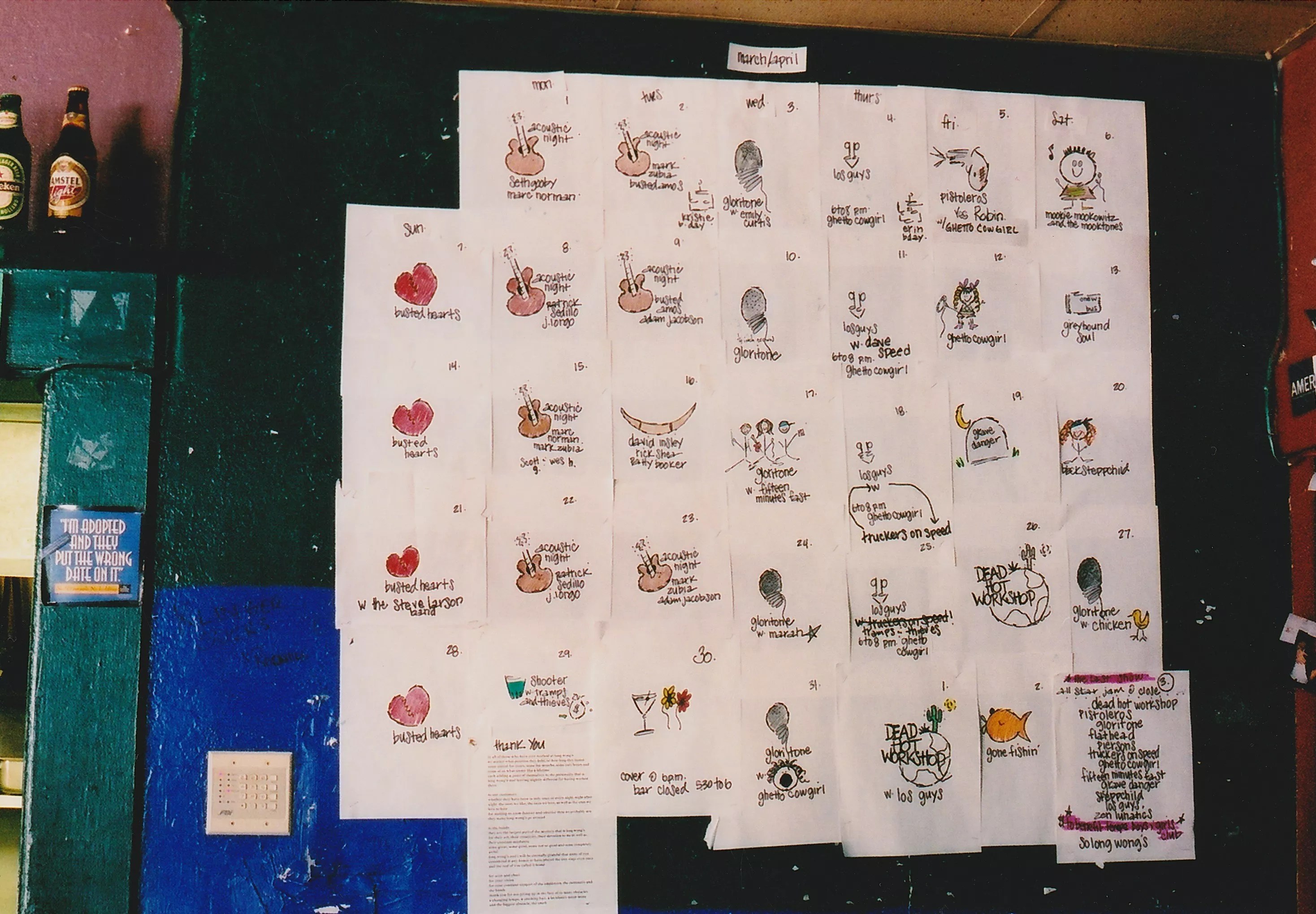

An example of Sara Cina’s beloved hand-drawn concert schedules.

David Rhodes

Those connections weren’t just born out of mere appreciation. So many other bands have stories where they only got in at Long Wong’s because of some other band they’d admired.

Rhodes: I got in there because Stephen Ashbrook let us open up for him.

We practiced a lot and played a bunch of shitty shows and a bunch of private parties. I paced myself before I approached Sara, and she said, “Get on with the band that’s already got a night.” So Stephen Ashbrook was on a Friday night, and so that was a big night. He gave me notes afterward and stuff and we played there a bunch more and opened up for Gloritone.

Wolfmeyer: I think it was Muddy Violets and Stone Bogart that helped us get our foot in the door at Long Wong’s. We were outsiders and we didn’t have anybody that was in for us, and so I felt like we earned our way in playing.

Rhodes: The migration of how these bands evolved, and how the members and the lineups changed and whatnot, it’s very incestuous, but it always has been. I think it speaks to the pedigree. If you played Long Wong’s, there’s a really good chance that you’ve gone on to do really good things, even if it’s on a really local or regional scale. There’s a whole sort of roster of great musicians who went through those doors and did great things.

An enormous crowd showed up to honor Long Wong’s last weekend of shows in 2004.

David Rhodes

The bigger picture

Long Wong’s was more than great shows and opportunities – it was the memories created by staff, performers and attendees.

Zubia: There was a whole other community and friendships that were developed just by that place being around. My brother-in-law and sister-in-law met because of Long Wong’s. They have two children who exist because of Long Wong’s. There are people that exist because of that place, which is weird to me to think of. I actually met my ex-wife there.

Carter: We played all these amazing shows and we released all these great records. We’re still friends 30, 40 years later. And I think that shows that that’s the mark of a healthy scene. Maybe it fizzled out, but the people still care. People are still very much a community around it, even if they’re not still doing stuff together.

Wolfmeyer: My highlight was that we played a Tuesday night, opening for a Steve Larson band. But I had a daughter that I gave up for adoption, and they got a hold of me and came down for her 13th birthday. And so Sara let us set up a table and let her in to catch us there. People came out and packed the place, and I got to look like a rock star for that little bit. It was like winning the Super Bowl at Disneyland on the Fourth of July or something.

Serving customers during Long Wong’s last weekend.

David Rhodes

But it’s not just about long-time friendships, either. Long Wong’s also had a larger impact from a cultural standpoint.

Rhodes: You had Mink Rebellion and Chalmers Green, which became Black Moods. They were still creating (bands). There were still musicians that were inventive and it was still a venue that provided the milieu for those people to continue to thrive.

That also raises ideas that Tempe could have been a greater musical “mecca” a la Chicago, Los Angeles and New York City. While that potential wasn’t entirely achieved – at least not for every band – there’s little denying that the sheer magic and potential were there.

Hansen Orf: It’s like someone in your fraternity all of a sudden becoming a doctor or something. He’s living on Camelback Mountain, and you majored in English, so you’re in an apartment. It’s just the way the thing goes. Everybody I think would have loved to have had that shot in that opportunity. But there’s bands in Athens, Georgia, and Seattle who are wondering the same thing. With Seattle, they got good producers and they got major-label money and all that kind of thing and a big push. But I think it could have easily been us, it could have easily been Tempe.

Sara Cina in the Long Wong’s office.

David Rhodes

A closing note on wings

And, of course, we can’t mention Long Wong’s without talking about their famous wings.

Wolfmeyer: It smelled like chicken wings, raw sewage and rock ‘n’ roll.

That’s just a thing that you can’t capture in an article, man. Beautiful and evil at the same time.

But it’s Cina who has perhaps the best descriptor of Long Wing’s wings, not only as a tasty snack, but a genuinely poetic notion about what really made Long Wong’s so significant. More than bands or sound quality or iffy plumbing, it was the community that was forged for decades in this little corner on a street that’s long since outgrown it.

Cina: There’s a secret where people don’t know: wings are so easy because the ingredients are pretty much all the same.

And the way people do wings now is very different than they did before. So we would have the canisters of all the different sauces – mild, medium, blah blah. You’re putting in grease and the sauce would get flavored from the wings being dumped in it all.

Now, most places do the opposite; they’ll swirl the wings around in it. So it doesn’t get any seasoning or flavor or whatever. And I feel like that is why Long Wong’s does have that mythical quality.

Every band, the people that worked there, everyone that went there, all that stuff, just every single one of those things left flavor in that place.