Norm Hall / Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

The Arizona Diamondbacks want public money to pay for expensive upgrades to Chase Field, and they’re making big promises in order to secure it.

Debuting along with the team in 1998, Chase Field is the only stadium the team has ever known. Owned by Maricopa County and built with $238 million in taxpayer dollars, the retractable roof stadium was once the pro sports jewel of the Valley. But as the stadium has aged, much of the last decade has been defined by ongoing squabbles between the team and county – or tenant and landlord – over whose job it is to fix it up.

The team has floated the idea of seeking a new stadium elsewhere in the Valley or even leaving Arizona altogether. But now, it’s pledging to spend $250 million to upgrade the stadium – after having already spent nearly as much sprucing it up over the years, the team says – if the Arizona Legislature passes a bill to spend more tax dollars on stadium improvements.

If passed, the bill would set aside tax revenue already being paid – as the bill is currently constituted, state sales tax collected from purchases at the stadium, a portion of the county’s excise tax and the state income tax of team employees – for the purpose of massive stadium upgrades. It’s hardly a no-doubter off the bat, as both the city of Phoenix and the county have registered concerns about diverting tax revenue that’s currently spent on other services. But key stakeholders met last week to hash out some of the differences, and Gov. Katie Hobbs has already signaled tentative support for signing it.

Key to the bill is an unenforceable portion at its bottom. Under its “Legislative findings” section, the proposed law says the Diamondbacks “will contribute at least $250,000,000 of the professional baseball franchise organization’s own monies” to upgrade the 27-year-old stadium. But that big, shiny number is one the public can take only on faith. The legislature cannot compel the team to spend its own money, but only put in writing that the team has promised to do so.

So, as lawmakers attempt to push the bill over the finish line, there’s a question worth asking: How good are the Diamondbacks at keeping their promises?

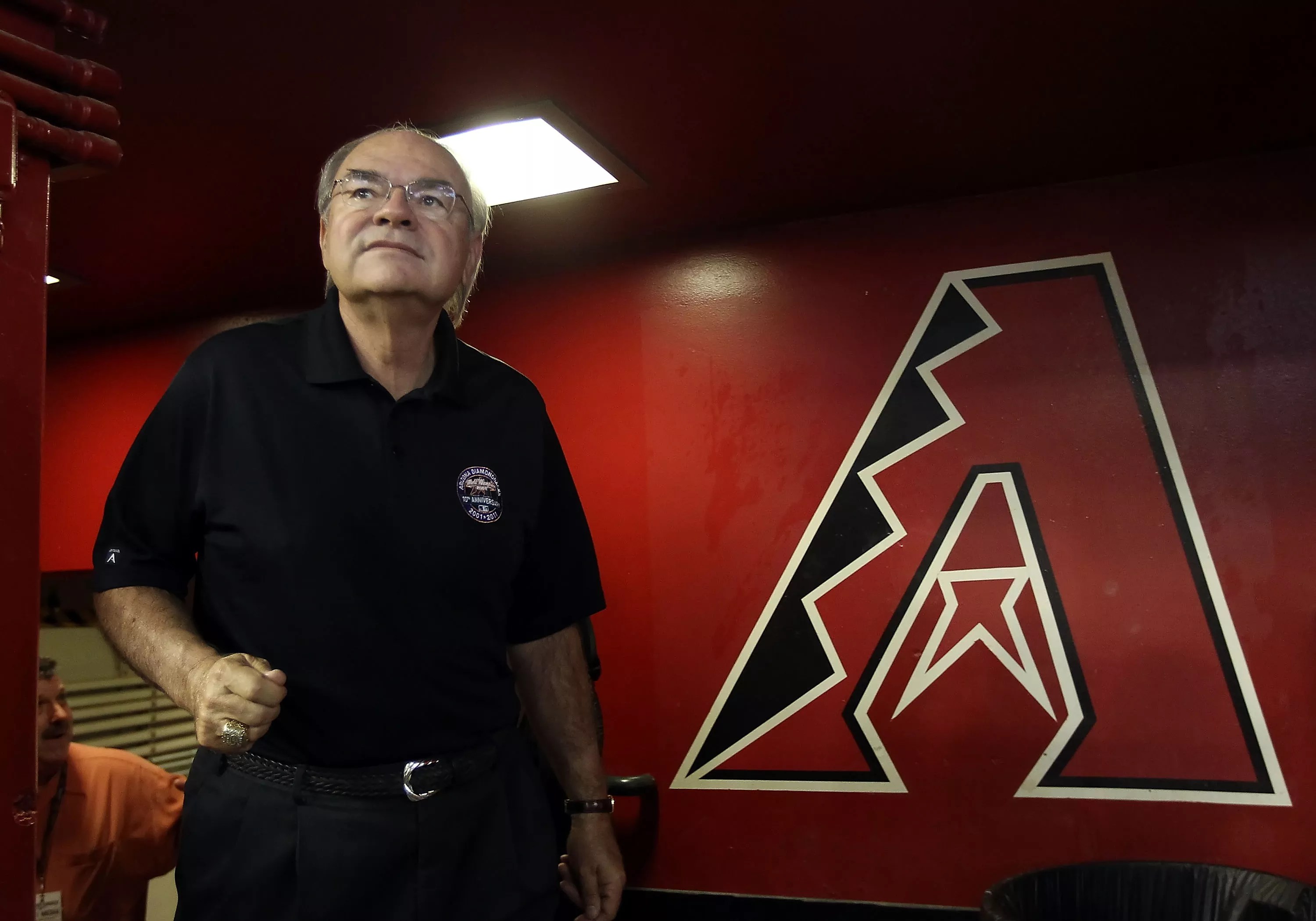

Diamondbacks president and CEO Derrick Hall said the team does set aside million a year for stadium repairs, as a 2018 deal with the county demands. But the team doesn’t put that money into the account that the agreement specifies.

Christian Petersen/Getty Images

Missing payments?

To answer it requires examining the team’s current agreement to use the ballpark.

In 2018, to settle a lawsuit brought by the team over stadium repair costs, the team and the county struck a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that gave the Diamondbacks more control over the stadium. Included in the agreement was a trade-off: The team would take over responsibility for repairs in exchange for the right to book concerts and other non-baseball events at the ballpark. The profits from those events – as well as an additional $2 million a year – would be put into a Chase Field Reserve Account for the explicit purpose of stadium fixes.

Crucially, the MOU gives the team sole control over the reserve account and does not allow the county – and, therefore, the public – to see what goes into it. The only glimpse into how the Diamondbacks are using the money comes from quarterly stadium repair expense reports the team submits to the Maricopa County Stadium District, whose board of governors is composed of the five county supervisors. Through a public records request, Phoenix New Times has obtained all of those reports. For the last four years, those reports have included a balance of the reserve account.

The reports reveal a few interesting things. One is that the team has indeed spent regularly on stadium repairs, which the MOU says must fall under four categories of “qualifying work” – essentially, safety repairs, plumbing and cooling repairs, roof repairs, and repairs to the scoreboard and sound system. Since the agreement went into effect in September 2018, the Diamondbacks have spent $17.6 million out of the reserve account for such fixes.

(Only once, when the team used reserve account money to pay for a pricey new artificial-turf field, did the county object. Then-county board chairman Bill Gates sent a letter arguing that installing the turf is not “qualified work,” though the team has insisted that abandoning natural grass eases the burden on other systems that the reserve account would pay to repair.)

The other revelation is that the team has definitely contributed to the reserve account, but not as much as the MOU would seem to demand. Since 2021, when the team began including the balance of the reserve account in its quarterly reports, the Diamondbacks have increased the account’s balance – either through deposits or investment growth – by $8.5 million. Yet considering the requirements of the MOU, that number seems a bit short.

Putting $2 million a year into the account over four years would account for nearly all of that total. But that would mean the team cleared only $500,000 from non-baseball events since 2021. That seems unlikely given the caliber of the events the team has attracted: Elton John and Bad Bunny in 2022, Morgan Wallen and Billy Joel in 2023, Journey and Green Day last year, plus an annual college football bowl game and many other shows.

What’s missing from the reserve account? Diamondbacks president and CEO Derrick Hall and team CFO Tom Harris say it’s the $2 million a year. In an interview last week with New Times, the two team executives said the franchise has not been depositing the required yearly payment into the reserve account and is instead setting that money aside elsewhere.

“What you’re not seeing is correct,” Hall said. “We’ll take the $2 million and we have it in our own fund.” He added that the team is fulfilling its duties by accounting for that commitment on its books. “It’s parked,” he said.

Meanwhile, Harris said the county is fully aware of that arrangement. “The county knows that. This isn’t any surprise,” Harris said. “We’ve had this discussion with them several times.”

The language of the MOU isn’t particularly ambiguous. It says that $2 million “will be paid by the Team into the Reserve Account” each year. Instead, the team is keeping that money out of public view. Reached for comment on the team’s practices, the county disputed the interpretation that the yearly $2 million payment could be siloed elsewhere.

“The language in the 2018 Binding MOU makes clear the Team is required to deposit $2 million per year in the Reserve Account,” said county spokesperson Jason Berry. “The County has communicated (that) all requirements of the MOU remain. Maricopa County remains committed to finding a long-term solution to keeping the Diamondbacks at Chase Field.”

In January, Diamondbacks owner Ken Kendrick suggested to reporters that the team keeps a slice of what it makes off of concerts and other non-baseball events at Chase Field, which would violate the terms of a 2018 deal with Maricopa County.

Christian Petersen/Getty Images

New revenue stream?

What the team isn’t doing, Hall insisted, is spending any of that money on anything other than stadium work. The alternative appeared to be the case in January, when the team introduced star pitcher Corbin Burnes, whom the Diamondbacks signed for six years and $210 million. Asked that day about running a record payroll – especially given the team’s lack of a regional TV deal – team owner Ken Kendrick listed off a variety of new revenue streams the team now enjoys.

The team makes money off a jersey patch ad and a sportsbook that opened at the stadium, Kendrick told reporters. Then he mentioned “all the concert revenues.”

“You guys are sensitive to the concerts and what they used to be. You’ll recall – I do – for 20 years, we didn’t get one cent from any event that played in this ballpark other than our games,” Kendrick said. “Now every event that’s in this ballpark, we get a share of. It’s not uber-lucrative, but it’s all brand-new money.”

If the team is indeed pocketing a share of concert revenue, that would be an explicit violation of the MOU with the county. That money is meant to go only to stadium repairs – for which the team did not have to pay before the MOU was struck – and not to a new star pitcher or any other non-stadium expense.

Asked if he wanted to clarify Kendrick’s statement, Hall said that all net concert revenues “go to the stadium” and that “there are new revenue streams, but we do not consider non-baseball events as one of those.” If the money added to the reserve account consists only of the team’s non-baseball revenue, as Hall and Harris say, then the Diamondbacks have made and deposited $8.5 million from non-baseball events over the past four years.

That it takes this much untangling to discern what’s being done with the stadium’s reserve account can be chalked up to a lack of oversight mechanisms in the MOU. The county can view what comes out of the account but not what goes in. Nothing requires the Diamondbacks to open their books. As lawmakers attempt to craft a grand compromise to keep the team at Chase Field for decades to come, that might be a lesson: Build in some accountability processes.

Hall said last week he’s optimistic about working out the kinks on the proposed law. He also said the team is amenable to such oversight. Whether the stadium is still governed by the county stadium district or by a new state entity, Hall said the team will “have to show each year what we’re spending, so they’ll keep a running tally. They’ll also have to approve what we’re using it for.”

That would be similar to the current agreement with the county. How well are the Diamondbacks living up to that one? That’s up for interpretation.