alexsl/Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

Shortly before the 2024 election, I found myself standing outside of a Phoenix megachurch called Dream City after attending a monthly event called Freedom Night in America, hosted by Turning Point USA’s Charlie Kirk. I was speaking to a small group of attendees when a middle-aged woman suddenly lowered her voice, clenched her fists, and shakily informed me that her biggest concern was that “Democrats are going after the kids.”

Her comment was jarring, but not out of the blue. She was referencing an idea that had been woven through the presentations from the pulpit that night, one that linked audience members’ concerns about abortion, border policy and public school curriculum – the idea that a demonic cabal of liberal elites is hell-bent on harming children. And that it is imperative for God-fearing American Christians to join forces with Donald Trump in order to stop them, whatever the cost.

Until that moment, our conversation had been friendly. I had introduced myself to the group as a researcher interested in their takes on the event, which I had visited to better understand the growing alignment between churches like this one and right-wing groups like Turning Point USA. The conversations I had that night, however, confirmed what I had been hearing from many leaders within the evangelical world – that fear, paranoia and conspiracy theories have taken far deeper root in this community than most outsiders recognize. And that confronting these forces was necessary not only for the health of the church, but for the survival of democracy itself.

One of the evangelical leaders raising alarm bells about this issue is Caleb Campbell, the lead pastor of a mid-sized church in North Phoenix called Desert Springs Bible Church. Caleb had watched firsthand as his church changed over the past decade. By Caleb’s account, his message had not changed much. In his sermons, he had long spoken about welcoming the immigrant, caring for the vulnerable and working toward racial reconciliation. But slowly at first and then suddenly, his congregants changed.

In the midst of COVID-19 church closures, Black Lives Matter protests and Trump’s re-election campaign, his congregants turned to right-wing media personalities who promoted a funhouse mirror version of Christianity. It was aggrieved, militant and power hungry. When Caleb proved unwilling to mirror that back to them, many went in search of a church that would.

Around 80% of his congregants ultimately left the church, some accusing him on their way out of being an atheist, a Marxist and even demonic. Amid the stress of it all, Caleb got COVID, then shingles, then facial paralysis. By September 2020, he told me, he had become “a shell.” He met with some of his pastor friends and told them he planned to quit. Not because he didn’t want to be a pastor anymore. As he put it, “I was just completely finished emotionally, spiritually, physiologically. Just a wreck.”

If Caleb’s story had ended there, he would have been in good company. Scores of pastors left their posts following Trump’s ascendance to national political power in 2015, when those who refused to tow the MAGA line were harassed, threatened or fired.

But Caleb’s story didn’t end there. And that is the other reason I ended up in Phoenix shortly before the 2024 election. I was reporting on Caleb’s current work as a national leader in a budding movement to resist this growing extremism within the evangelical world, and how Phoenix, writ large, reflects this shift towards extremism as well.

Caleb Campbell argues that purveyors of Christian nationalism encourage fear, paranoia and conspiracy theories in order to justify this anti-democratic takeover of the country.

Ruth Braunstein

A Christian nationalism illness

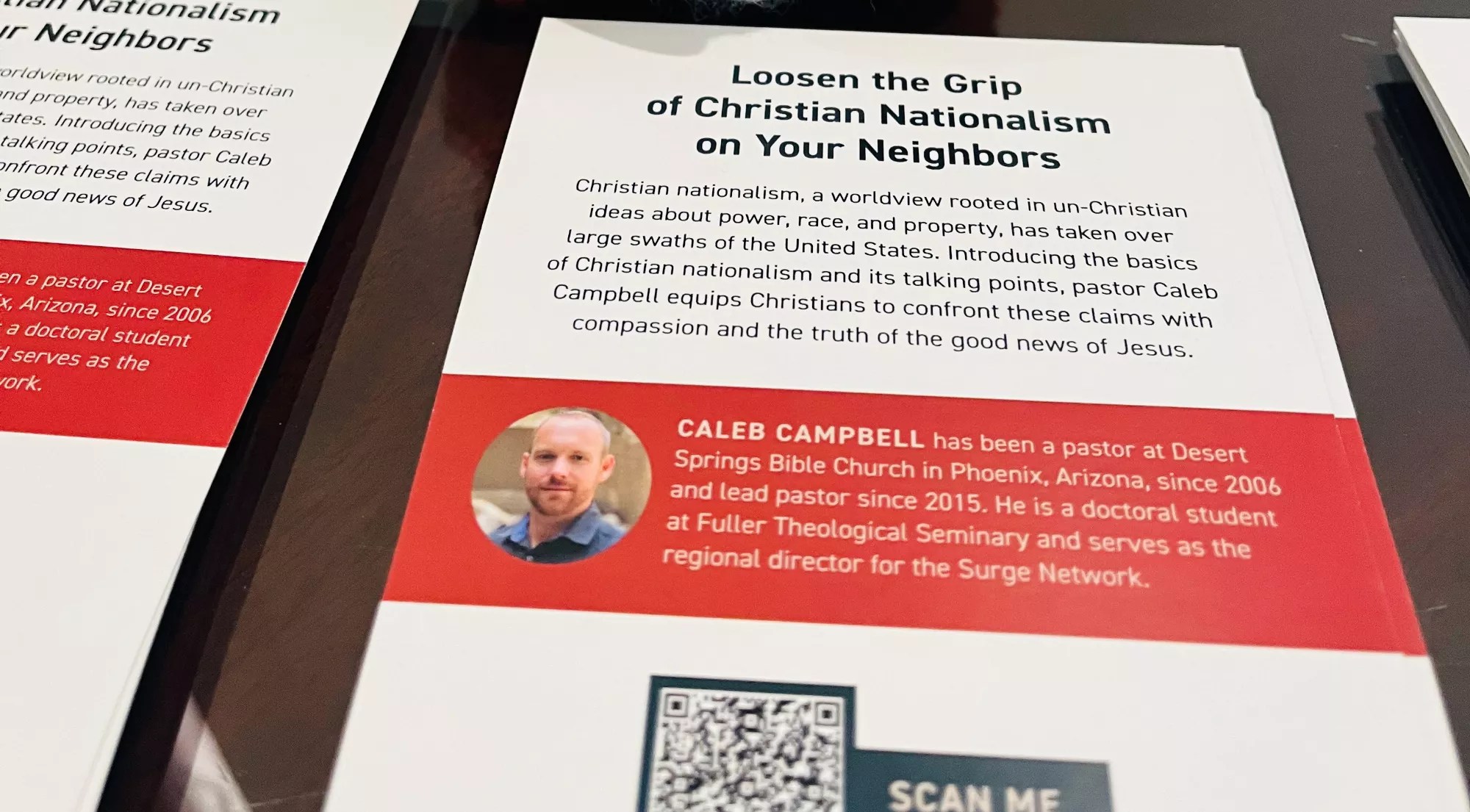

As I chronicle in a new audio documentary, “When the Wolves Came: Evangelicals Resisting Extremism,” in the years since 2020, Caleb has regained his health, recommitted to his work as a pastor and rebuilt his church. He also published a book, “Disarming Leviathan: Loving Your Christian Nationalist Neighbor.” In it, he diagnoses the illness that he believes has taken hold of the evangelical world since Trump’s ascendance to political power, and also offers a cure.

The illness, in his view, is Christian nationalism. Christian nationalism does not simply refer to Christians who love their nation, but rather the idea that Christians should seek dominion over the nation and its inhabitants. At the heart of this dominionist ideology is the belief that God intended for the United States to be a homeland for white conservative Christians, that its laws and culture should be based on white conservative Christians’ interpretations of scripture, and that white conservative Christians should rule. The rest of us, in this view, are here by invitation only.

Caleb argues that purveyors of Christian nationalism encourage fear, paranoia and conspiracy theories in order to justify this anti-democratic takeover of the country. Yet he insists that those who are concerned about Christian nationalism should not stoke fear and paranoia in return. Instead, he argues that Christian leaders should serve as missionaries to the Christian nationalists in their community, just as he and his colleagues at Desert Springs Bible Church are doing in Phoenix. This means extending love, patience and hospitality rather than arguing; and creating churches that abide disagreement rather than requiring conformity.

Over the past year, Caleb has been traveling the country to speak at churches and pastor conferences, record his podcast and be a guest on countless others. The strategy he developed in Phoenix has caught the attention of a growing community of evangelicals and political conservatives who share his concerns about the MAGA movement’s hold on the church and the Republican Party nationally. Many of these individuals reported feeling religiously and politically “homeless” until they began to coalesce into a movement of sorts over the past few years.

Together, they are sending up a signal flare to others like them, and to potential partners from outside the evangelical world. It is a call to speak prophetically in a pivotal moment, despite the costs.

The current president campaigned on a promise to exact vengeance on his political opponents and anyone who dared hold him accountable to the law or the truth. Now in office, he is making good on this promise. He is especially focused on institutions that have historically served as independent arbiters of law and truth – courts, law firms, universities, media organizations and even churches.

Americans now face a costly choice – to lay low or speak truth to power. In making this choice, we would benefit from studying others who have already stood at this difficult crossroads. We don’t have to look back hundreds of years or halfway around the world to find them – indeed, right in our own backyards, in Phoenix, pastors like Caleb were like the canaries in the coal mine of the country’s extremist turn. They offer a model for how to lead in precarious times, shepherding their flocks away from extremist ideas and towards democracy.

Ruth Braunstein is an associate professor of sociology at the University of Connecticut and the president of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion.