Marcy Ellis

Audio By Carbonatix

In 2019, Phoenix New Times began probing the margins of Arizona food culture in an attempt to illuminate a specific type of cuisine emerging in America’s great Sonoran Desert, and to highlight the overlooked people working magic with ingredients used here for centuries. We ventured out into the state’s arid wilds and culinary unknown, spotlighting artisans that were pioneering new approaches to food, perfecting timeless regional dishes, and otherwise honoring the quirky, elusive, singular, gemlike ingredients of the desert.

Sonoran Arcana – the resulting column, 10 of which are excerpted below – helped shed light on arcane Sonoran foodways and define what we came to call New Arizonan cuisine.

Here’s what it tastes like.

Elephant food, a shrub with juicy leaves and a zap like sorrel.

Chris Malloy

Foraging Wild Food in the Paved Streets of Old Town Scottsdale

In a northern sweep of a 120,000-square-mile desert, under palm trees and faint sound waves flowing from distant saloons and the odd busker teasing an electric kora, a tented bazaar hums. It hums in the center of streets of western junk shops, clothing boutiques, hums on byways that swell at night with beautiful people in various stages of dress and intoxication, funneling to and from nightclubs. It hums, a warren of food vendors, a Rivendell of perfume lemons and bao buns jammed with chorizo, a tranquil nexus of sellers and buyers who eat well.

This bazaar, you may know, is the Old Town Scottsdale Farmers Market. One of its roughly 100 vendors, Mark Lewis, believes that some of the market’s best food comes not from its stands.

He believes that it grows wild, ripe for plucking from the ground.

In dirt beds. In alleys. In seed clusters and tree pods. By steam pipes. Near car tires. Under timeworn adobe facades more than three feet thick. Food grows in Old Town, on streets we heedlessly walk: a universe of edible plants.

On an early winter Saturday, Lewis – a botanist, a former ASU professor, a graying man with khakis, glasses, and Paipai blood – started his edible urban plants tour.

Lewis points out mustard greens, lamb’s quarters, and purslane.

Chris Malloy

“Okay,” Lewis said, crouching in an empty parking space, gesturing at a two-foot plant, “so the area we’re at right now, probably you wouldn’t think too much about this being a place where you want to get your food. But if you look down at the wall here, you see this plant sticking out. That’s amaranth.”

Amaranth is a New World plant. It was a staple of indigenous Americans, from the Aztecs to Tohono O’odham; you can eat its seeds and greens. Lewis is highly aware of the past, plant and human. His market stand’s name is “Chmachyakyakya Kurikui: 8000-year Crops: Ancient-Future Foods Remembered.”

After identifying amaranth, he looks to others sharing its asphalt crack. “This right here is the triangle leaf,” he says. “This is quinoa. This is the relative of the expensive plant that you get at the supermarket.”

Lewis rounds a cinderblock enclosure, turns down an alley. In an even tone, he speaks with the erudition of a man who eats a diet of more than 75 percent foraged food, with the thought trains of a botanist who savors most of the Sonoran’s many edible plants.

In the alley, Lewis identifies lamb’s quarters. (“All of our modern lettuces have been bred out of a plant like this.”)

He stoops to a growth of mustard greens. (“They’re perfectly edible.”)

Lewis emerges from the alley, turns onto Second Street. A white sedan sloshes past, then a yellow sports car. He points out aloes and grasses.

Nearing the end of the tour, after whipsawing his listeners with Latin and Tohono plant names, Lewis walks north and turns into a wide alley. He has one more plant to showcase: tomatoes.

Lewis stops when he gets to the back of a restaurant, freezing at the head of a parking spot. “There’s your ‘maters, right there,” he says. “When you look at them, there’s flowers on them. Now, later in the season, they’ll have fruit. Every year they have fruit. They’re beautiful little tomatoes.”

The unmistakable, spade-shaped leaves and starry yellow flowers tremble in light wind. Lewis just stares.

“So we’re surrounded by food,” he says, turning back to the market, tents now visible. “People say, ‘I don’t have room for a garden.’ But plants don’t care what you have room for. They come right up.”

Fan palm “dates” and syrup from Community Exchange.

Chris Malloy

Dates Are the Syrupy Dark Horse of Arizona Agriculture

Once upon a time, Arizona was a major date state. It began when date palms were brought to the Americas by Spanish missionaries in the early days of colonization. Around the start of the 20th century, these trees and their descendants were no longer producing in large quantities, so the U.S. Department of Agriculture began to import dates from places like Morocco, cherry-picking favorites from the world’s 3,000 varieties.

In the U.S., date palms grow only in southern California and Arizona’s Sonoran Desert. Fatefully, the genus of the date palm is Phoenix.

Charleen Badman of FnB is a big fan of dates. She’ll toss a date called the Black Sphinx into preparations like a salad of Bloomsdale spinach, goat cheese, pita chips, and radishes sliced so thin they’re virtually 2-D.

Sphinx Date Ranch in Scottsdale.

Chris Malloy

The Black Sphinx was discovered by Roy Franklin in Arcadia in 1928. Today, these dates still grow in Arcadia backyards. You can find them fresh come date season (early fall) at, for one, Sphinx Date Ranch in Scottsdale. There, Rebecca and Sharyn Seitz carry on the specialty date business launched by Franklin and his associates before World War II.

And depending on where you live in the Valley, you might have an offbeat date varietal growing in your backyard.

“In 2011, I bought a property and didn’t know what dates were,” says Janna Anderson, owner of Pinnacle Farms, just west of South Mountain. “Now I’m a date farmer and have more Maktooms than anyone in the state.”

This year, most of her crop of Maktooms, a wrinkly and rare Iraqi varietal, went to Cassie Shortino, chef at Tratto. Shortino uses them with pork. “We cook them in sherry vinegar and sugar, and make a kind of syrup,” she says. “We use that to glaze pork chops.”

The sugar coats the pork well, and allows the meat to caramelize nicely. It also fits the restaurant’s paradigm: Arizona terroir plugged into an Old World blueprint. Just like the tale of dates in the Sonoran.

Chase Saraiva starts to fill the outdoor coolship with wort.

Chris Malloy

The Most Ambitious Beer Project in Arizona

Beer equals wort plus yeast and time. Yet Chase Saraiva, who gets paid to artfully navigate this equation, is driving two 350-gallon tanks of wort away from his Gilbert brewery stocked with select yeast. That’s because Arizona Wilderness Brewing Company lives up to its name: Saraiva is headed out to make beer in the wild.

Since opening in 2013, Arizona Wilderness, owned by Jonathan Buford and Patrick Ware, has pioneered the Valley’s beer scene, pushing what people drink in Arizona into funky, woody, sour, strange, beautiful, atmospheric territory. Buford, Ware, and head brewer Saraiva [Ed. note: Saraiva recently left the brewery] produce thoughtful, dependable versions of beer styles widely popular in America (IPA, lager) while leaning heavily on grain, fruit, and other inputs from local farms.

But what sets Wilderness apart is its YOLO moonshot projects. Foeders. Mixed-style beers. Beer-wine hybrids. And most of all, the biannual Camp Coolship project, a pluperfect distillation of this brewery’s local ethos and madcap style.

Like ancient Egyptians or the vintners recalled by Pliny the Elder, Saraiva – driving into the wild for Camp Coolship 8 – will be catalyzing fermentation using ambient microbes, tiny yeasts floating around in the air. As 100 percent ambient yeasts will be used, fermentation will be “spontaneous” and produce a “wild ale.” Without a prepackaged or otherwise tightly controlled yeast, brewers have limited leverage over how flavor will change, sour, funk, and wander.

Parked, Saraiva emerges. After greeting fellow campers from Wilderness and some brewery representatives invited from afar, Saraiva, who looks like a young chemistry professor, lifts a tank’s hose. He holds it over a shallow pan between the two truck-mounted tanks.

Brewers from near and far hanging out by the mobile coolship.

Chris Malloy

Liquid like milky chai spreads thinly across the shallow pan, the coolship. A smell of pretzel – freshly baked pretzel – diffuses. Jonathan Buford, wearing a brown jacket with prancing ponies, strums a guitar and sings improvised songs about wort and brewing. Gnats arc through the sunlight, bobbing and flitting erratically, randomly. Invisibly, so do tiny yeasts.

Since 2016, when the project started, Wilderness has brought two versions of its mobile coolship into the wild a total of eight times. Because these fermentations take so long, only two of the eight beers have been released.

There are many obstacles to brewing a wild ale in the wild. Logistics. Memory. Weather. Humidity. The mightiest is time. An Arizona Wilderness Coolship beer takes one to three years to ferment. This is liquid magic at the speed of continental drift.

“I think it captures a specific time and place,” Saraiva says, of culling wild yeasts and bacteria from the wilderness. “Because what’s in the air right now isn’t going to be what’s in it tomorrow, three hours from now, four hours, or three years from now. It’s capturing the here and now.”

Using wild yeasts forges a fleeting connection to an elusive present, to a concrete here and now. Wild microbes in the air change rapidly: from place to place, day to day, by the plants and animals and seasons and clouds and wind and raindrops and guitar players and human activity in the woods. When Saraiva uses ambient microbes to catalyze fermentation, he is using microbes ephemerally alive in a time and place of Arizona that the world will never know again. He is locking that time and place into a bottle, writing its spirit into a beer.

So what, then, will he be locking into Coolship 8?

Once the coolship fills, the day’s work is finished. Wort stays out. Microbes enter on their own. The brewers migrate to the lawn chairs by the bonfire and a long white tent. Jammy music and twangy country blast from Ware’s truck.

Ware passes around an experimental beer-wine hybrid. There are pastry stouts, double IPAs, helles, lagers, sours. Dusk falls. The white spotlight of a nearby camp sears the giant night. A portable grill throws the scent and sizzle of charring meat over to the campfire. Stars punch through the inky veil. Yeasts float onto cooling wort.

After midnight, it rains. Saraiva lets some collect, then covers the wort.

In the morning, the coolship has been uncovered. Saraiva is off handling a carbon dioxide tank, soon to pump the wort back into the steel tanks. “Um, so yeah, we got some rain last night,” he laughs.

Camp later breaks. Saraiva guides the mobile coolship back to the highway. Later, he’ll move the wort to 500-liter French oak puncheons. And there, in the dark, wild yeasts will awaken four days later to work their ancient magic, alchemy that will last up to three years, when, upon release, even though Saraiva’s path as a brewer has since led him away from Arizona, the vanished time and place of Coolship 8 will rise to life again.

Andrade’s haul of wild chiltepines from Sonora, Mexico.

Chris Malloy

One of the World’s Best Peppers Is Native to Arizona

Rene Andrade plops $4,000 in peppers onto a table at Ghost Ranch, the south Tempe restaurant where he is head chef. Though minuscule, wobbly-ball red peppers pack a mighty punch. They are one of Arizona’s great foods: the chiltepin.

“This is the pepper I grew up with,” Andrade, a native of Nogales, Mexico, says over his chiltepin stash dried from late 2018 harvests. “This is the pepper that was in my life forever. I ate it on everything. I put it on everything – salsa, ceviche, carne asada, drinks.”

During his childhood, Andrade would often travel to his family ranch in Baviácora, Sonora. On the ranch, wild shrubs begin to show color bursts in fall, when their spicy fruit turns a florid red.

The chiltepin is often considered the “mother,” the ancestor of all other chile peppers we know today. And it is much better than more common peppers. It has an intense, lemony, almost tropical brightness before its high-throated heat flares, burning with depth and gentle fury. It can be up to 20 times hotter than a jalapeño.

Andrade juiced seven limes and crushed eight chiltepines to make his family’s aguachile.

Chris Malloy

Despite its virtues, the pepper remains something of an outsider in metro Phoenix. You are more likely to come across its descendants. One obstacle is that the pepper prefers to live and die without human intervention. It staunchly resists gardens and farms and, besides, tastes best wild.

Like most other very hot peppers, the chiltepin is more than just heat. The appeal of the world’s hottest peppers is rooted in many things, among them the tiny beautiful flavors that flash before the heat strikes. A pepper might bring notes of smoke, cinnamon, and citrus before the tidal wave of fire.

The chiltepin’s intensely fruity character has drawn a cadre of supporters. “It’s bright and packs a giant bang of flavor,” says Silvana Salcido Esparza of Barrio Cafe. “I personally think it’s the most flavorful of all chiles.”

Esparza uses them in aguachile and pozole. Charleen Badman of FnB uses them on top of fried eggs. Chris Bianco describes chiltepines as “hot and delicious” and “much more powerful than their heat index.”

“I spent years trying to get this obscure mushroom from China, and now I’m getting it,” Matt Carter, chef behind The Mission and other Valley restaurants, says of the chiltepin. “That’s cool, but not as cool as this pepper.”

In an effort to get more people to adopt this fiery chile of his youth – and not wanting the tradition of it to die – Andrade did something remarkable late last spring: He gave away most of those $4,000 worth of peppers, spreading the love and the fire.

Velvet Button checks on Ramona Farms heritage blue corn.

Chris Malloy

Shepherding the Crops of Arizona’s Past Into the Present

Just a short drive from metro Phoenix, in a part of the Gila River Valley where the river has dried up due to upstream human diversion, the Buttons, led by Terry and Ramona Button, keep Ramona Farms with spartan rigor and boundless love. Here are ancient, modern indigenous crops that are made for their environment – and taste great. Yet only a handful of eateries in the Phoenix area use them.

Their daughter Velvet Button starts to leave the garbanzo field. She stops on the edge and plucks a pod from a low plant, similar to all the others in the yellow rows around her. The lumpy pod looks about as moist as a ruffled potato chip. Velvet rolls the pod between her fingers. It crushes to dust, blows away. Parched garbanzos remain, jewels of the low field drying before harvest.

Beneath Velvet’s strappy sandals, the soil is fabulously cracked, like thin ice on a pond – only there won’t be ice anywhere on this June day. The heat is well on its way to triple digits over Ramona Farms.

Velvet trades the garbanzo fields for her car. Driving, she points out an alfalfa field.

She talks about hospitals and canal projects, about local artist Amil Pedro and Akimel O’odham legend Chief Azul, the tribe’s last chief.

The original tepary varieties Ramona Farms started growing in the 1970s: white and brown.

Chris Malloy

Soon, the low green shoots of a corn field show. Velvet parks. She walks into the rows of young plants. The machine-gun trilling of a killdeer is muffled by the vast chorus of crop leaves rustling. The field holds a Hopi blue corn varietal, still a few weeks from harvest. It also holds Pima 60-day corn, an Akimel O’odham mainstay known as kiikam huuñ.

“When it’s grown in optimal temperatures, it’s gangbusters,” Velvet says. “That corn grows like crazy.”

Area chefs do many things with Ramona Farms corn. Velvet herself has many uses for it. She nixtamalizes corn using bean and wood ash. She makes tamales, porridges, mush, tortillas, corn c’emet, and other old and new preparations.

Velvet climbs back into the car. The green acreage and blue sky in the low bowl of mountains slide by in a bucolic dream.

We pass concrete canals skirting fields. Ramona Farms uses flood irrigation, letting pumped groundwater course across fields, watering crops. This is possible because Velvet’s uncle painstakingly leveled fields using lasers. Land he has reshaped, Velvet says, “is flatter than a pool table.”

Velvet now parks at a golden wheat field. Ramona Farms cultivates Pima, durum, and White Sonora wheat. The young wheat riffles and rustles in the wind with a colossal stirring sound, giving the field the peaceful magic of a golden ocean.

After talking about wheat-based indigenous foods like ceme’t and pinole, Velvet makes for a plot of tepary beans. These are leafy, shifting shoots in clods of brown soil. They point at distant, sacred mountains. When the plants are ready for harvest, beans will be white, brown, and black.

Velvet notes that her family bred the black tepary, the s-chuuk bavi.

White tepary beans, Velvet notes, are “sweet and buttery” with “a smooth texture.”

Brown teparies are “nutty and earthy” with “a texture of boiled pecan.” They keep their shape when boiled. “In a nice brothy soup, they showcase like little river petals – they’re so pretty,” Velvet says. “And when you cook the brown tepary bean, oh my gosh, the kitchen smells like rain.”

Tamara Stanger and Cotton & Copper sous chef Nolan Barth with freshly collected mesquite pods.

Chris Malloy

An Amazing Desert Food Might Grow in Your Backyard

“A lot of people don’t know about mesquite,” says Tamara Stanger, chef at Cotton & Copper in south Tempe. “And it grows everywhere in the city, and most people have it in their yards.” Stanger, an exponent of foraging and wild foods, starts to gather mesquite pods for culinary use come early summer, the beginning of their season.

She uses mesquite pods in an array of preparations, right in line with her reputation for skill and creativity with wild foods. She started using the desert-adapted legume years ago, when she was baking at Pig & Pickle, where, from time to time, she’d mix mesquite flour into bread dough.

Though mesquite has long been an arboreal icon of the Sonoran, only three of the tree’s more than three dozen species are Arizona natives: honey, velvet, and screwbean. These trees thrive in minimal rain, thanks to roots that can tunnel 70 feet deep. Their bluish leaflets swish as the monsoon winds pick up, as if about to reveal some great, final secret.

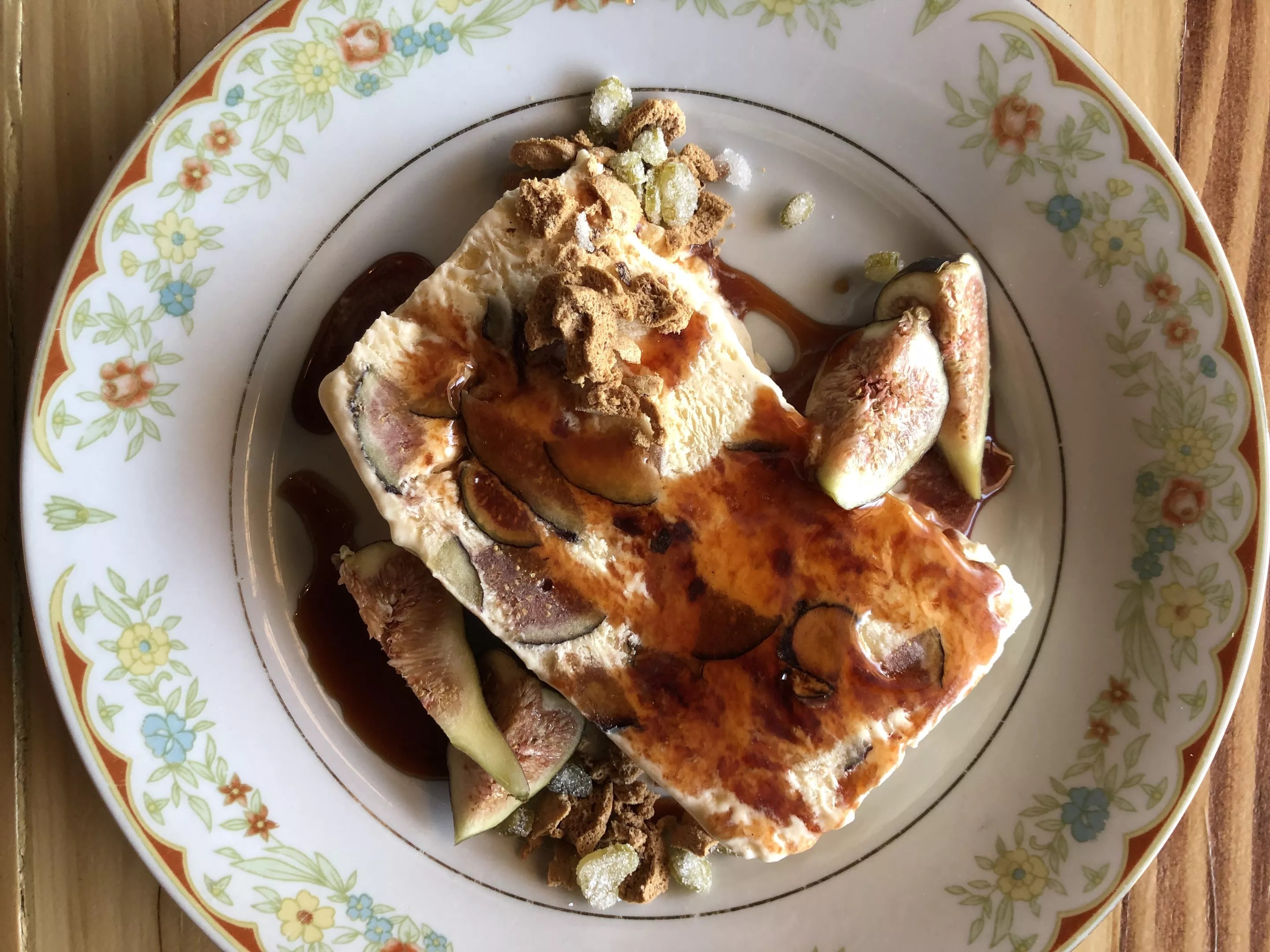

Fig semifreddo prepared with mesquite syrup, made by Tamara Stanger.

Chris Malloy

They smell ashy and pungent when burnt.

They give smoke that imbues food with sharp flavor.

They can be shrubs, dwarf trees, or 20 feet tall. Their pods are eaten by jackrabbits, songbirds, livestock, and other animals, like us.

Felicia Cocotzin Ruiz, a traditional healer, chef, and indigenous foods activist, uses many parts of the mesquite tree for a variety of purposes, including the pods for food. “Most people think of it kind of as a nuisance,” she says. “For me, it’s an ancestral food, a food that has nourished my family for thousands of years.”

Ruiz, who came to the Valley from Tewa country in New Mexico, harvests mesquite until the early summer monsoons arrive. She uses pods for syrup, traditional drinks, a porridge like Cream of Wheat, and much more.

Like any foraging, collecting mesquite comes with a set of best practices that should be researched beforehand. The cardinal rule is to skip pods fallen to the ground. But there are others. And that’s why rare services like those provided by Greg Peterson of GrowPHX are useful.

In early summer, in conjunction with GrowPHX and Desert Harvesters, Peterson set up his recently purchased mill at the Urban Farm Fruit Tree Program nursery and ground mesquite for all comers. Some 26 pounds went to Peggy Sue Sorensen, a “wild foods enthusiast” who teaches classes on mesquite.

Early summer mornings, Sorensen often spends hours gathering pods, but only from the most flavorful trees. She says that some trees have pods that taste great, while others aren’t worth picking from. Sorensen is known among friends for a drink she makes from mesquite pods and water. She calls the coiled, 6-to-8 inch pods “the sugarcane of the desert.”

Chef Ryan Swanson uses liquid nitrogen to make prickly pear “dippin’ dots.”

Chris Malloy

How Kai Creates New High-End Arizonan Food

It’s just after noon on a Saturday, the second day Ryan Swanson has been developing a new dessert. The Kai chef’s creative process often takes five weeks of tinkering, leaving time for any possibility to emerge.

The dish being created on his morning off? A Sonoran riff on key lime pie.

“I kind of wanted to do a key lime pie, but with cactus,” he says. “Instead of key lime, I wanted to do nopales.”

Since opening in 2002, Kai has been a leader in writing the next chapter of Arizona food. Swanson and the head chefs before him have devised artful menus that exalt and elevate Sonoran ingredients. Many come from the Gila River Indian Community, which owns the celebrated restaurant. Like the rest of the Kai menu, Swanson’s key lime pie will be a creation new to the world.

A small pie made the previous day sits on a ceramic plate, its center glistening a pale green from cactus. The plate sits under four sleek-hooded copper lights. Swanson hoists a tank of liquid nitrogen and pours. Liquid nitrogen collects in a copper saucepan. Cold fog plumes over the metal table, curls down its sides. Swanson produces a plastic bottle of prickly pear gastrique: fuchsia liquid mixed with lime juice, lime zest, and elderflower vinegar. He squeezes drops into the pot. They freeze instantly, creating, Swanson says, “dippin’ dots.”

Swanson emulates service, pouring prickly pear gastrique tableside.

Chris Malloy

“There’s usually eight bullet points I go through when I’m making a dish,” Swanson says. As he reaches for a plate so he can begin assembly, eight numbered points face him, scrawled on paper.

1. What’s the theme?

2. What’s the story? (“If I had to give this a story, I’d probably dedicate it to Velvet Button,” Swanson says. “She foraged all these ingredients or they grew it at Ramona Farms. This is kind of a tribute to Velvet for all her hard work.”)

3. What’s the flavor/season?

4. What’s the idea? (The idea is to channel key lime pie’s vivid tang using desert plants, mostly cactus.)

5. What’s the plate? (The plate is a saucer sloping up to a raised, circular hollow. Now, Swanson sets the pie in the hollow. Atop the pie he adds a flat circle of meringue – perfectly cut to fit the hollow, obscuring the pie beneath.)

6. How to serve it?

7. Does it suck or does it work?

8. What’s the name?

Quickly, Swanson zests a lime over his dish yet to be named. Like sound, the fruit’s perfume instantly fills the kitchen air.

From here, assembly is swift. In a flurry of spooning and tweezing, ingredients appear atop the white meringue. Swanson adds citrus lace, small green growths from orange trees. He perches two neon-yellow cucumber flowers. “Cucumber and, I think, lime and cactus – they just go together,” he says.

Moving to the stove, Swanson quickly heats up a saucepan of the purple gastrique, then brings it and the plated pie out to the dining room.

Standing at a table, holding the saucepan high, he tilts the rim. Drops of purple splash atop the cactus pie’s white meringue. With a flute soaring from the hidden restaurant speakers, Swanson tastes the first version of his new dessert.

Salt Mine Wine, a small vineyard in Camp Verde that focuses on Italian grape varieties.

Chris Malloy

Growing Grapes and Making Wine in the Desert

The climatic quirks of southern Arizona test vintners, monsoons for one. Spring frosts can also wipe out crops after budbreak, the visible beginnings of the annual growing season. And even apart from climate, there are the variables beyond lack of knowledge that come with being a younger wine region.

Kent Callaghan of Callaghan Vineyards believes the desert has qualities that give wines unique thumbprints. In the wine world, there is the pervasive idea of terroir, the notion that the taste of place comes through, that the sunshine and farmer and methods and harvest and soil and humidity and wind and rain shape flavor. For example, Chablis has a chalky flavor because of the soil its chardonnay grapes grow in. Similarly, the Arizona desert has its own territorial signatures.

“Between the iron and the calcium here, you definitely get distinctive characteristics,” Callaghan says. “[The wines here] have denser tannins. You can feel it in the mouth. It’s more concentrated. There’s more guts.”

Arizona vines in June, the grapes steadily sliding toward ripeness.

Chris Malloy

Arizona wines, like the wines of any place, vary between growing regions and vineyards. But there are general tendencies that can be underscored, and places, like Callaghan, where Old World varieties thrive.

A specific Callaghan wine with Burgundian roots is what got Sam Pillsbury of Pillsbury Wines into Arizona winemaking in the first place.

“I discovered a chardonnay made by Kent Callaghan,” he says. “It was the most extraordinary chardonnay I had ever had in my life.” After tasting this wine, Pillsbury drove down to Willcox the next day and bought 40 acres across the street from the plot of grapes that Callaghan used.

After pondering opening a vineyard in his native New Zealand, Pillsbury, decades later, is thrilled to be in Arizona. “The high desert is amazing because it’s so clean,” he says. “There’s not the concerns about things like rot, which you have in more humid climates.”

“The chardonnay that we grow is just insane,” he says.

Pavle Milic, beverage director at FnB and owner of nascent Los Milics Winery, echoes the view that desert wines turn out a little differently. “Unique,” he says, “is an understatement.”

Callaghan agrees, citing soil and sun, diverse planting to safeguard against climate variability, the scene’s relative youth, and the fact that the people growing the grapes are still, at this stage, the same people running the tasting rooms. He says, “The wines in Arizona are so much better than they were 10 years ago that it’s funny.”

Desert forage dried, candied, and otherwise prepared are the heartbeat of Sonoran Scavengers.

Chris Malloy

The Desert Comes to a Farmers Market Near You

Sonoran Scavengers, a new stand at the Old Town Scottsdale Farmers Market, has products unlike the farmed fruit, farmed vegetables, and prepared foods sold by its neighbors. Karen Bedell sells jams made from forage: wolfberry, barrel cactus, prickly pear, mesquite, manzanita. She sells flour ground from amaranth, blue corn, and palo verde beans. She even bakes what she gathers into cookies, into muffins.

“Almost everything that we use is local to Arizona, with the exception of the pineapple,” Bedell says. “And most of it comes out of our desert.”

Karen Bedell of Sonoran Scavengers.

Chris Malloy

Twenty-four years ago, Bedell came to Arizona for a six-month stay that never ended. The desert presented different plants, a different landscape. These days, Bedell does most of her gathering near Buckeye, her home. “My backyard opens up to about 2,000 acres of farmland,” she says.

That allows her to forage “all the way to Gila Bend.” She also gathers in Rainbow Valley, where she’ll go camping, staying overnight in wild places to gather. Other times, she’ll throw her kids in the car and head on a trip. They’ll go forage. See a new town. An old mine.

She doesn’t stop for winter, like some Sonoran foragers do. The wolfberries, she said in the fall, were just coming back into bloom.

Bigger fruit, like wolfberries and hackberries, do better when closer to a water source. “Follow the washes,” she says. “I happen to know an area where water is close to the surface, and sure enough the wolfberries grow better there.”

And so she ventures downstream, gathering in wild places. “I read just about every book I could find on foraging,” Bedell says. Browsing the forms and colors of her wares, listening to her patiently explain the unknown to customer after customer, spooning bracing samples of mesquite and fig jelly, you believe her.

These mesquite-flour rolls are made from a long-evolving recipe.

Chris Malloy

Dreams of Perfect Desert Bread and Tortillas

Chris Lenza, executive chef and overseer of Café Allegro, has been tinkering with his mesquite dinner roll recipe for 10 years. That’s also how long the cafe has been around. Lenza, a sous chef at Allegro when it opened, took the reins of the ambitious program two years after it began.

“We source as much as we can within 150 miles of the museum,” Lenza says. That includes heritage corn, flours, nopales, mesquite, and cactus fruit tonged from the courtyard. All find their way into a seasonal menu.

One week, there might be a meatloaf of grass-fed beef and Hayden purple barley. Another, there might be pozole swimming with Ramona Farms Pima 60-day corn, served with grilled nopales tossed in prickly pear vinaigrette.

And there might be a simple, warming vegetable soup that channels the rainy desert spirit of tepary beans.

When Lenza speaks about desert ingredients, his eyes shine and his voice brims. “I would be really upset with myself if I wasn’t giving the guests local, regional cuisine,” he says.

Chris Lenza in the MIM courtyard.

Chris Malloy

Big projects seem to be what animate culinary artisans who embrace the ingredients of the Sonoran Desert. Having nailed his mesquite sourdough roll recipe after 10 long years of editing, having developed a mesquite telera roll for special occasions, having bullseyed a salsa fermented from guajillo chiles and prickly pear fruit, Lenza has moved onto his next big thing: heirloom Sonoran corn tortillas.

“This is what I do every Saturday,” he says, his voice going low and furtive at one of his cafe’s tables. “I’m trying to figure out a way to make Ramona Farms heritage corn into a corn tortilla.”

Lenza says he has these tortillas just about down. The last step is to strike a balance between the absolute unconventional beauty of a tortilla made from these heirloom corn strains, and what customers are expecting.

He sits back in a cafe chair and slips into a big smile, desert tortillas on his mind. His voice goes loud again.

Lenza says: “They’re really good.”