Preston Zeller

Audio By Carbonatix

The loss of a loved one can change the very DNA of daily life. Whether it’s from a long illness or a sudden accident, the seemingly endless deluge of grief, uncertainty, and listlessness can be devastating.

For Preston Zeller, he made it through thanks to the power of his art.

Flashback to 2017, and Zeller’s older brother, Colin, died of a drug overdose. To help cope, Zeller began his own extended mourning process by painting. Artistic expression, he said, has always been an integral part of his daily life.

“I went to film school at Chapman University in California,” Zeller says. “I’ve been making films in various shapes and sizes for a long time, whether that’s R-rated films or commercial-type films.”

His colorful, formless works of abstract gave him an outlet for the wellspring of ideas and emotions he grappled with on the daily. In all, he’d paint one new piece for a full 365 days.

“The thing about abstract [art] that I’ve always enjoyed, and this is to your point, is that it’s not a single, literal snapshot in time,” Zeller says. “You’re creating a sense of someone when they were 10 years old, or you’re capturing a landscape before it burned down.”

Yet when he stared upon his collected works he still felt as if there was something more to do.

“I got this huge collection of paintings and I have these visions of what I want to do,” Zeller says. “And so I remember staring at them at one point and saying, ‘Hey, what if we hung them up?'”

That idea would eventually transform into The Art of Grieving, a 70-minute documentary that follows Zeller and his family and friends in finishing the art and arranging the sizable mosaic, which eventually hung in his former Texas home. (Zeller relocated to Gilbert for work and family after wrapping the film.)

Since the documentary debuted in 2021, it’s won three awards for Best Documentary at national film festivals. (That’d be Bridge Film Fest, Los Angeles Film Awards, and Love Wins Film Festival, plus some honorable mentions elsewhere.) It’s currently available on the free streaming service Tubi, and is also set to debut on Amazon Prime this July and Apple TV before the year’s end. And it doesn’t take long into the film itself before you realize why it’s resonated with so many people in so many ways.

“There’s this old friend of mine who teaches film, and he’s done a lot of documentary work,” Zeller says. “He brought up this notion of how this documentary is going to appeal to several different audiences. There’s this personal contemporary view, this contemporary view of mental health, and then there’s this historical look at it all.”

The one cohesive thread, though?

“Grieving is definitely not something that anyone thinks about until you have to go through it,” Zeller says.

The historical aspect, Zeller says, saw him researching and exploring art history. During that period, he says he came about a similar pattern when it came to artists, famous and lesser-known, tackling the subjects of death and grief. There were seemingly countless portraits exploring these ideas across time, cultures, and artistic approaches.

“The history piece kind of gives it all context,” he says. “Like, why would I be doing this? Have other people done this before? So I started researching, and there’s all these interesting use cases. And there was a catharsis in there for me.”

He adds, “It’s actually trippy just how many people are actually artists, and I call this out in the documentary, who didn’t paint about death or anything like that before. Then they did a similar thing I did, and they started talking about it. For me, it weaves this thread that, as long back as we could really tell, people have probably used some form of [art] to try to understand [grief] their own way, and that it’s not a novel thing. It’s people doing art because of what it potentially did for them.”

That historical bent also touches on religious practices and lineages. Zeller, who comes from “somewhat of a Christian background,” also used the film to delve into his own beliefs.

A shot of Preston Zeller’s mosaic work.

Preston Zeller

“I went back and read parts of Scripture in light of it all. And [grief’s] all over the Bible,” he says. “I just never read it in that way. That’s the reason why I put Job in it because the book of Job is the most epic story of loss in the Bible. So you say, ‘Okay, wait a minute. These things that I’ve been exposed to are never talked about or are something that I had to think about.’ I’m looking at that in a different way than everything in my life.”

It was about more than just spirituality, though. This whole process also inspired Zeller to think especially closely about the work he’d done in the grander tradition of painting.

“There were times where I was maybe more cognizant of if I’m angry or I feel depressed,” he says. “You know, a more extreme surfacing of emotions. And then oftentimes, painting was an escape from all the things I didn’t want to feel. And then I’d stare back at it and I would visualize how the colors were changing and say, ‘Why did you use that technique? Why did they use that coat or these colors on that day?'”

And, perhaps most important of all, the added commitment to personal honesty made it easier to delve into his relationship with Colin. It’s a depiction that, across the course of the documentary, feels both earnest and unblinking in its depiction of a very specific sibling relationship.

“First and foremost, I didn’t want to be inauthentic about how I was portraying it,” Zeller says. “I shared a bedroom with him up until I was a sophomore or junior in high school. I was there firsthand through a lot of his early days of drug addiction. If I tried to hide that, which I’m sure some of my family would have been happy about, it wouldn’t have been real.”

He adds, “I think for someone to really understand why I would go through with this project, I think that it wasn’t just a sibling relationship. It was a sibling relationship that included this element of drug usage, which so many more people [have] experienced as fentanyl [use] has exploded.”

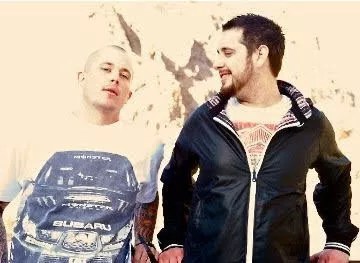

The Zeller brothers pose together in a 2009 family photo.

Preston Zeller

Part of that, Zeller says, is that given his brother’s prior military service, he felt as if he owed to other men and women who might have been in similar shoes.

“I had people reach out to me,” Zeller says. “And they’d say, ‘I had some family member that was in the military, and they’re taking all these pills.’ And so even in that sense of touching on that being a veteran and having a drug addiction that’s really common. So I think that would’ve been a huge disservice to those watching it and probably would make it a lot worse.”

But ultimately, and this may go back to Zeller’s larger comments about the “personal contemporary view,” this whole project may have been about delving into the ideas of family and community, and strengthening those bonds as a means of earnestly celebrating life.

“There were times I’d go, ‘If I stopped this now, will anyone care? Will I care?'” Zeller says. “My wife was certainly instrumental in that. The one thing I don’t really share in the documentary is that it was very much a family affair. My wife and kids are experiencing the ramifications … And so every day I do this painting and then bring it to my kids. And they were the most interesting to hear like, hey, what do you see in this?”

Perhaps as an extension of that, Zeller also got to see how other people routinely reacted to the pieces and the project in general.

“We also had someone come over to the house for some very temporary reason, and they would stop in their tracks and then start talking about [the paintings],” Zeller says. “Like, ‘Oh, I see this over here and I see this over here and I see this over here.’ And that was more enjoyable. People, these total strangers, often saying, ‘Oh, this resonates with me because I lost so-and-so.'”

And from those initial joyous (albeit perhaps slightly strange) interactions, Zeller has been able to have greater conversations about grief. And from those, he’s found new ways to connect and uplift people.

Preston Zeller at work on a piece of his mosaic.

Preston Zeller

“Knowing that other people have lost someone themselves, and it makes them reflect on their own experience and their own journey, that brings total joy,” he says. “But then having people giving feedback and saying, ‘Oh my gosh, you know, this has made me do X-Y-Z more than I normally would have.’ That makes me so happy and is so validating for the project.”

In addition to the movie’s release on the streaming platforms, Zeller is trying to find space to assemble the entire mosaic once again. He’s had some early conversations with “a gallery with a pretty big presence in Austin, Texas, and even Scottsdale. And I need to restart those conversations.”

But there’s one venue he’s really hoping to secure.

“I’m really trying to get this into the Phoenix Art Museum,” he says. “It belongs somewhere where people can see it.”

Because, at the end of the day, through all the insights and new understandings, not to mention the connections with others, Zeller has learned one especially vital lesson. It’s that, for as universal as grief is, it doesn’t really start to get better until we all come clean to the one person that matters the most.

“And one thing I’ve realized is that people inevitably need to get to the place where they say, ‘I’m ready. I’m ready to do something about it,” Zeller says. “No one’s ever going to talk you out of it or talk you into that moment. It’s so individualistic.”