S’edav Va’aki

Audio By Carbonatix

When discussing museums and their collections, repatriation is a sensitive topic. Over the past few years, more museums across the nation have voluntarily returned artifacts to their countries and cultures of origin.

But when it comes to Native American human remains and associated funerary objects, U.S. law is clear: They belong to the tribe or organization from which they came. It’s outlined in the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990, sponsored by Arizona Rep. Morris K. Udall.

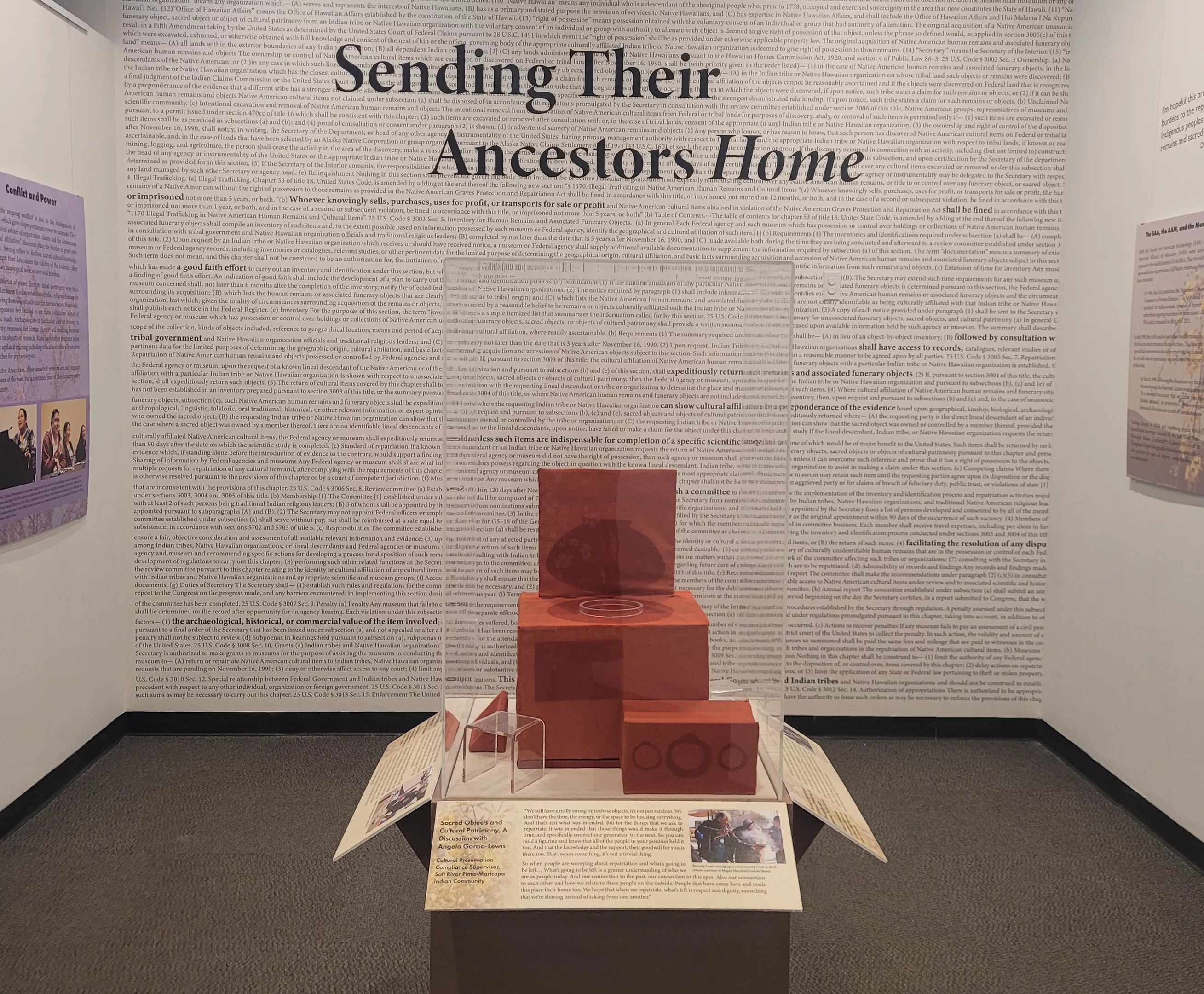

“Sending Their Ancestors Home,” an exhibit at the S’edav Va’aki Museum (formerly Pueblo Grande Museum), gives insight into this legislation and its effects on tribal cultures and museum ethics with placards and a 24-minute audio presentation.

“To imagine a family member in a box in a room on a shelf in the dark is very traumatic; to know that they’re not at peace,” says exhibit designer Caitlin Dichter. “Through repatriation, you can begin the healing process.”

Caitlin Dichter worked with local tribal communities to create the exhibit Sending Their Ancestors Home at S’edav Va’aki Museum.

S’edav Va’aki Museum

Created in close consultation with the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community (SRPMIC) and the Gila River Indian Community (GRIC), the exhibit opened in June and runs through May 14, 2024.

Dichter says “Sending Their Ancestors Home” was a “passion project” for their tribal partners. It traces NAGPRA through the history of colonizers robbing graves to the activism that led to the law and what more needs to be done for healing.

This includes reworking the law to give tribes and Native Hawaiians more agency over the remains, rather than letting museums and institutions make the decisions.

“NAGPRA leaves a lot of power in museums’ hands,” says Lindsey Vogel-Teeter, the museum’s curator of collections. “New proposed regulations are seeking to give tribal communities more say.”

In the 2010s, staff at S’edav Va’aki Museum began meeting regularly with SRPMIC to be more respectful, understanding and communicative. The museum removed all remains and funerary objects from display and has repatriated 99 percent of the more than 300 remains available for repatriation in its collection – a strong track record compared to many museums.

“Our museum specifically has worked hard to build partnerships with tribes,” Vogel-Teeter says. “We’ve worked hard to consult with tribes the way they want to be consulted with.”

In contrast, an investigation by ProPublica revealed that only about half of the 210,000 Native American remains in American museums have been returned.

“Tribes have struggled to reclaim them in part because of a lack of federal funding for repatriation and because institutions face little to no consequences for violating the law or dragging their feet,” according to Pro Publica. It posted a database searchable by institution, tribe or state to find out more.

The bulk of the exhibit “Sending Their Ancestors Home” consists of placards that outline the sordid history of grave robbing, activism to pass NAGPRA and efforts to strengthen the law.

S’edav Va’aki Museum

The placards in the exhibit tell a sad and shocking history. One reads, “There are 609 museums and universities reported as having Native American human remains, with over 110,000 not available for repatriation to tribes.” The University of California, Berkeley, for example, holds 9,060 ancestors.

Other placards trace the history of how and why some institutions collected remains and fought against NAGPRA. The video presentation’s audio excerpts are powerful, too, with tribal representatives explaining why repatriation is important to them and their cultures and how hard it can be, even with NAGPRA.

Reylynne Williams, GRIC’s cultural resource specialist in its Tribal Historic Preservation Office, says on the audio loop that all tribal communities have oral traditions, which aren’t always accepted as preponderance of evidence for repatriation.

Some tribes “seek to work with archaeologists, anthropologists, you know, to confirm our existence and to provide additional preponderance of evidence,” Williams says. “And it makes it difficult for us because we know that our own community, the O’odham, were not widely researched.”

Another facet of the exhibit is the entire text of NAGPRA on one wall, not just an excerpt. It shows how shockingly brief the statute is for such a complex subject.

That’s why it’s important to tribes and Native Hawaiians that the law be reworked. National NAGPRA in 2022 proposed revisions, including removing the term “culturally identifiable” and “instead repatriating by geographic origin,” as the last placard states.

If visitors take away one thing from “Sending Our Ancestors Home,” Dichter said, it would be to think twice when they go to another museum.

“If they ask, ‘Should that really be on display?'” she said, “then it was an effective exhibit.”

S’edav Va’aki Museum is located at 4619 E. Washington St. Summer hours through September are 9 a.m. to 4:45 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday. Admission is $6 adults, $5 seniors and $3 students. Call 602-495-0901 or visit the museum’s website for more information.