Sommer’s lovely voice, his turn of lyrical phrase, and his cherubic good looks certainly were enough to keep him in the showbiz game long after this big, messy, outdoor concert concluded three days later. But Sommer was a hippie, and hippies didn’t trade in fame.

“It’s too heavy, man,” Sommer reportedly told his agent, Artie Kornfeld, a co-producer of Woodstock and recent president of Capitol Records. It was Kornfeld who offered Sommer the privileged place as

Kornfeld, who’d had his most recent success launching family pop band The Cowsills, knew an opportunity when he saw one. Publicity-wise, having his newest client open a mammoth music festival was better, he knew, than a spot on The Ed Sullivan Show, bigger than a month on the road with Joni Mitchell or a well-publicized pot bust. It would put Sommer on the map as the guy who kicked off what Kornfeld knew would be a groundbreaking, counterculture rock ’n’ roll happening.

Kornfeld knew something else: Sweetwater, the L.A. rock band originally scheduled to open, hadn’t shown up yet. The very stoned crowd was getting restless. Kornfeld needed an opening act, and he headed straight for his newest client.

Sommer is said to have peeked at the crowd of 300,000 hippies gathered in this cow pasture in Bethel, New York, in various stages of undress for a promised “three days of peace and music,” and flat out refused to go on.

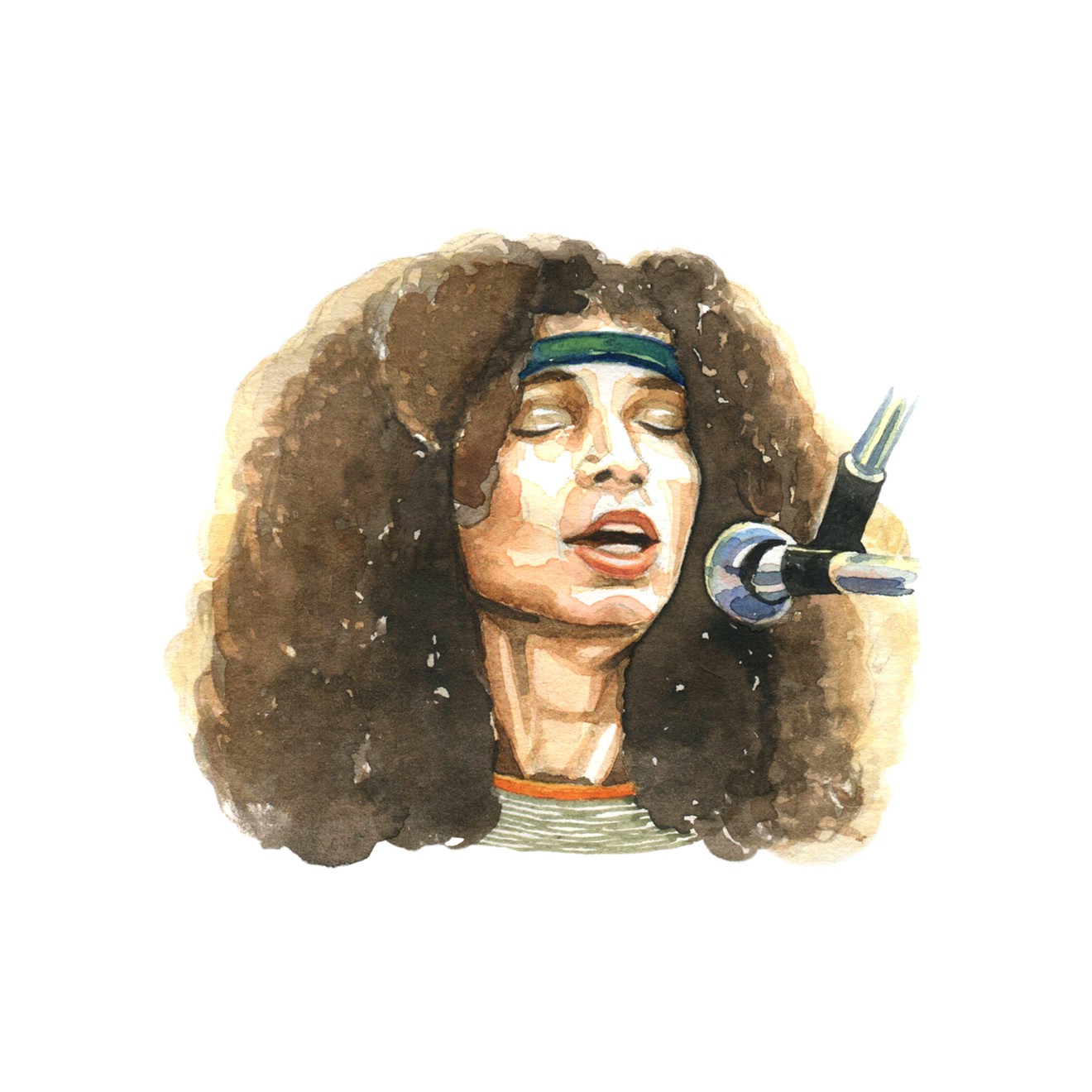

Kornfeld had hedged no musical bets with Sommer. Maybe he was counting on the kid’s recent stage experience as one of the leads in a new Broadway musical called Hair (that’s Sommer’s big, billowy afro on the cover of the original Playbill), which ended with Sommer and the rest of the cast doffing their tie-dyed duds. He took all his clothes off in front of crowds of uptight New York theater fans, Kornfeld may have thought. Singing to his own people will be cake.

But Sommer had never performed his own music before a crowd before — and certainly never for an audience of 300,000. He choked, and Richie Havens went on in his place. Havens played for three hours, stalling while Sweetwater (who’d been detained by the cops) and other performers caught in traffic made their way to the festival. It was a career-making performance that peaked with one of

Bert Sommer isn’t anywhere to be found on that album. He isn’t in any of the several versions of Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock documentary film, either. It would be 40 years before part of Sommer’s hourlong set at Woodstock, one that’s often referred to as the best of the first-day performances, would be documented in any appreciable way, in one of the lesser Woodstock box sets. By then, Sommer was long gone, having died of a respiratory illness in 1990. His contribution to Woodstock remains so forgotten that his name doesn’t appear on the commemorative plaque placed on the festival site in Bethel, New York.

Bert Sommer eventually took the stage at Woodstock. He went on third, after Sweetwater, who turned up two hours late. Sommer and his band, hastily assembled from an ad in The Village Voice, performed for nearly an hour. He opened with “Jennifer,” a gorgeous ballad he’d written about the singer Jennifer Warnes, his former girlfriend and castmate in the L.A. production of Hair. (In a clip that surfaced later on Woodstock 40 Years On: Back to Yasgur’s Farm, Martin Scorsese, then a young film editor, cuts several times to a Warnes lookalike with long, blonde hair and granny glasses who’s seated in the audience. It’s creepy.)

Seated barefoot and cross-legged

“I was involved in the two most famous counterculture events of the ’60s,” Sommer told Melody Maker in the 1980s. “Hair and Woodstock. That and a token will get you on the New York subway!”

So what happened? How is it that Bert Sommer had, until very recently, been all but erased from Woodstock history? This 20-year-old had a major label record deal. He was a deeply talented musician whose manager was one of the producers of Woodstock and president of the label he recorded for. Why didn’t these facts shove his debut album, which contained many of the songs he performed at Woodstock, onto turntables and airwaves?

Part of the reason is just old-fashioned commerce. Sommer’s debut LP, The Road to Travel, was released on Capitol Records. But Woodstock was a Warner Bros. product, and therefore the film and its 20-song soundtrack album, both released in 1970, featured Warner artists

It didn’t help that Sommer’s music was hard to pigeonhole. He looked like a central casting hippie, but his sweet melodies sometimes wandered far from peace-and-love lyrics and into mawkish Mancini motifs. And then, he’d turned down that career-making first gig, which couldn’t have pleased his manager. Sommer spent the rest of his Woodstock weekend partying backstage, then wrote a song about the festival — his only hit, “We’re All Playing in the Same Band,” which peaked at No. 48 on Billboard’s singles chart in September 1970.

The rest of the decade was devoted to decline. Sommer recorded three more albums for various smaller labels, each of them a flop, the last of them produced by The Archies’ lead singer, Ron Dante. He wrapped up his career with an embarrassing turn in one of Sid and Marty Kroft’s Saturday morning extravaganzas, playing a member of a manufactured glam-rock band called Kaptain Kool and the Kongs. Sommer

He returned to New York, where he’d been born, and played local fairs with a band called The Newports. He married and fathered a child. The handful of articles published since his death suggest that the respiratory illness that took his life at age 41 may have been exacerbated by heroin use.

Nearly 30 years after Sommer’s death, he’s likely to be rediscovered. Last week, Rhino Records released Woodstock – Back to the Garden: The Definitive 50th Anniversary Archive, a 38-disc set and the first collection to include nearly complete sets from every Woodstock artist who performed. (