Turns out, they accomplished something far more significant, stumbling across a virtually untouched library of Birgittine manuscripts that survived historical upheavals including war and the Protestant Reformation. Only the nuns who lived there had ever been inside the cramped, disheveled library, which was opened to the scholars during their brief visit in October 2015.

The scholars included art historian Corine Schleif and musicologist Volker Schier, both with Arizona State University, as well as experts from other academic institutions – including University of Wisconsin-Madison and Stockholm University in Sweden, to name a few. “No one outside the monastery had ever seen them,” Schleif says of the manuscripts.

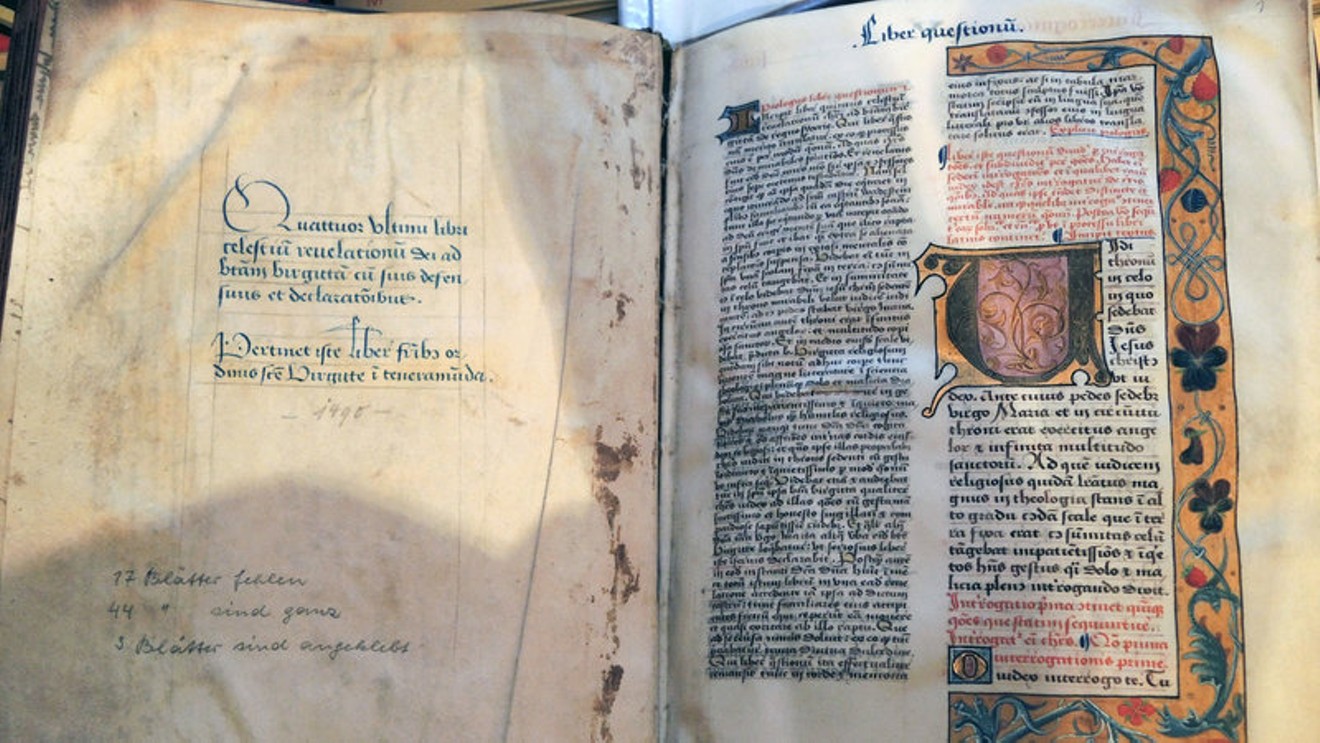

Housed within a huge complex filled with valuable works of art and ornate architecture, the library’s contents include an estimated 500 books, ranging from cookbooks to religious manuscripts decorated with images of sacred subjects. “It’s unusual to find a medieval library intact,” says Schleif.

In fact, it’s downright rare.

Portion of the Altomünster Abbey where a team including ASU researchers found medieval manuscripts.

Courtesy of Volker Schier

“We decided this was a rather dangerous situation,” Schier says.

So the ASU researchers sounded the alarm by reaching out to institutions with the capacity to handle such manuscripts and contacting international media.

They even launched an online campaign, alerting international scholars through a listserv, then creating a Change.org petition that’s since garnered more than 2,000 signatures calling for the “preservation and protection” of the library’s contents.

Scholars who discovered the Altomünster manuscripts attending an October 2015 symposium at the abbey.

Bevin Butler

Today, the ASU researchers are less concerned about the manuscripts’ fate, saying they learned in January that the Pope granted the local diocese ownership of the monastery – and the monastery announced it had no intention of selling the library’s books.

“This is a fundamental success for our group and the scholars who signed the petition,” Schier says. And yes, in case you’re wondering, plans to create the virtual abbey are still a go.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly indicated that Byzantine manuscripts were found. They were Birgittine.