"The mall is now closed. Please proceed to the exit. The mall is now closed. Please proceed to the exit.”

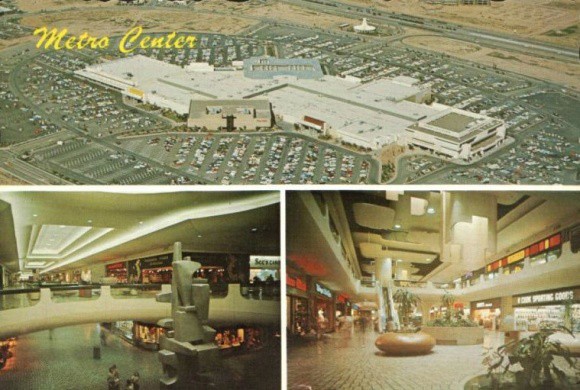

It’s 7 p.m. on Tuesday, June 30, 2020, and an era has just ended. On Phoenix’s west side, at what only a half-century ago was the farthest edge of the city, Metrocenter mall is locking its many different doors forever.

“Please proceed to the exit,” an amplified voice repeats. “The mall is now closed.”

A group of teenagers in medical masks rollerblade past a janitor who lazily scoots a broom. Nearby, an ersatz rock band performs an approximation of thrash metal in a seating area that used to house a two-story fountain. The band’s tiny audience politely bob their heads.

As recently as last week, the skaters and headbangers would have been chased out of here. Today, Metrocenter’s 17,276th and final day, is a bit of a free-for-all. People stand on the furniture in the mostly empty building. They perform synchronized dance routines in shop windows and drape themselves over barren display cases for better selfie angles. The handful of remaining shopkeepers and security guards look the other way.

“Okay, you guys, single file out the door!” a woman named Jan Ulrich hollers to the group of bored-looking kids she’s brought along to bid farewell to Metrocenter’s mostly empty storefronts.

“I grew up here,” she’d confided to the children — her three granddaughters and a couple of neighbor boys — about an hour before. “Over there was a place where a guy played the piano all day and you could stand and watch him. And back here was a pet store where Grammy bought a garter snake with her allowance money.”

The kids, each of them licking an ice cream cone, look distracted. “And back there was a big secret,” Ulrich continues. “It was a little part of the mall called The Alley, where you could go string love beads and make your own perfume.”

“Nope,” mutters a man who’s standing nearby, eavesdropping. “She got that wrong. The Alley was on the other end of the mall, and that pet store was upstairs by the ice rink.”

The man, who says his name is Timmy, is leaning against an empty kiosk in the center of the mall. “I grew up here, too,” he tells a stranger who’s stopped to watch a clerk lock the doors of Bianca’s Balloons for the last time. “I knew this place like the back of my hand. I had my first job here, at Orange Julius. We had these stupid costumes they made us wear. I got laid in the parking lot. 501s and a concert T-shirt.”

Today, Timmy is wearing a baseball jersey printed with the KUPD logo. “Best radio station ever,” he says, pointing to an inky scrawl over his stomach. “Signed by DJ Dave Pratt himself.”

On the floor above, a man named Nathan walks past shuttered shops and an empty sunglasses stall. He grew up in Utah, moved to Phoenix 20 years ago, and says he hasn’t met anyone who didn’t practically live at Metro in the ’70s. He’s visiting the mall for the first time. “Everyone I know went there,” he’ll email later that night. “I had to see it before it went away.”

Nearby, Michael Hooper’s wife is teasing him. She knows how much Metro means to him, that he started hanging out there in the late ’70s when he was barely 9 years old. “Do you want a Kleenex?” she asks.

“I really did expect to cry a little,” he’ll confess to a former neighbor a few days later. “But nary a tear came to my eye. The place I was walking through didn’t look like Metrocenter. They covered up the skating rink, took out the fountains, put in these weird skylights. The flooring wasn’t right. I walked around, but I didn’t feel a thing. Metrocenter was already gone.”

For a whole lot of people, Metrocenter’s closing last month (tenants had until yesterday to pack up and get out) marks more than just the death of another shopping mall, the latest in a long line of brick-and-mortar businesses murdered by online shopping and pandemic social distancing. Some are calling the demise of Metrocenter a final nail in the decades-old coffin of urban renewal, which emptied our downtown business district a half-century ago and launched suburban sprawl. Others say it’s proof of our town’s prevailing racism, the gradual migration of white people from economically challenged neighborhoods as they become more racially diverse.

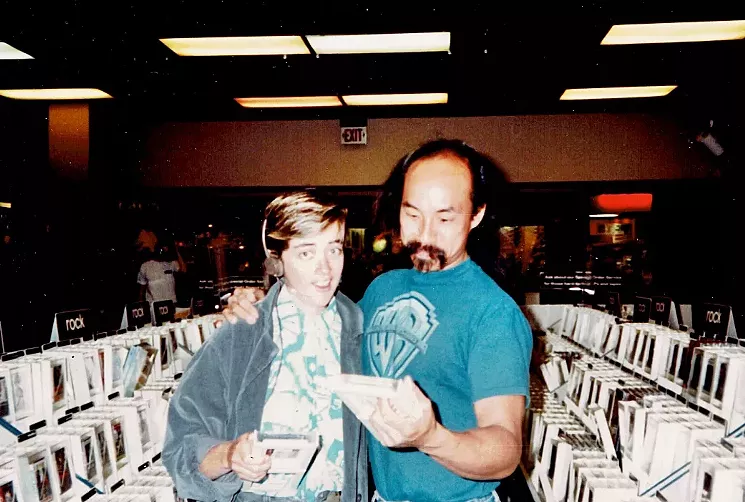

Mostly, though, the people who grew up hanging out at Metrocenter want to talk about the fun they had there, before it became a ghost town, back when they felt safe going there, and after they stopped shopping at Metro, which is what most folks call the once-popular, 1,400,000-square-foot mall. They like to chat about how they used to cruise Metro’s outer loop on weekend nights in the 1980s in a friend’s souped-up 1972 Cutlass Supreme or a VW bug, blowing off steam or maybe hooking up with a girl with tall, crisply permed bangs. They’ll post on the farewell-to-Metro Facebook page about the pair of cork wedges they bought at the Wild Pair in 1983 or demand a list of favorite places to eat at Metro’s airplane-shaped food court. They’ll talk about being an extra in Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, the 1989 Keanu Reeves comedy that filmed at Metro, or about the time that lady killed herself by leaping from the second floor onto the ice-skating rink below. (Everyone, it seems, was either there that day and saw her jump, or they swear it never happened.)

Actor Al Leong (right), who played Genghis Khan in Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure, and crew member Connie Hoy check out tapes at Sam Goody at Metrocenter in 1987.

Connie Hoy

“It wasn’t just that the demographic was changing,” says Metrocenter general manager Kim Ramirez about the mall’s demise. “When Carlyle Development Group bought the mall in 2012, they brought in Walmart and got some permitting done for a redevelopment of the mall. But we couldn’t get another investor, and so the redevelopment never happened.”

It was further downhill from there. An assessment of the property by Ramirez, who’s been with Carlyle for about a year, revealed expensive, pre-1990s maintenance issues that needed addressing before the mall could seek new anchors to replace the national chains that were bolting. “Everyone was already shopping online,” Ramirez explains. “Big stores were closing across the country. And then COVID happened.”

In response to the pandemic, the mall shut down for six weeks in March. Metrocenter, Ramirez reports, never recovered from the lost revenue. In mid-June, Carlyle announced that Metro would close for good at the end of the month, leaving only Walmart, Dillard’s Clearance Center, and a restaurant called Proper Eats open.

By then, Metro had already been a ghost town for several years. Everyone’s favorite west side mall was barely 20 years old when, in 1993, its parent company opened Arrowhead Towne Center, another supermall situated a scant 10 miles away. While Metro was losing popular chain shops and replacing them with lower-end Ma-and-Pa boutiques, Arrowhead was romancing upscale shoppers with new tenants like Sephora, Coach, and Phoenix’s first Apple Store. Increased crime in Metro’s surrounding neighborhood didn’t help, and a crackdown on weekend cruising slowed attendance at a mall that was already ailing. By the time the mall was acquired by the California-based Macerich Company in 2002, Metro was on the skids. Renovations in 2005 and a complete remodel two years later sent Metro mall rats scampering.

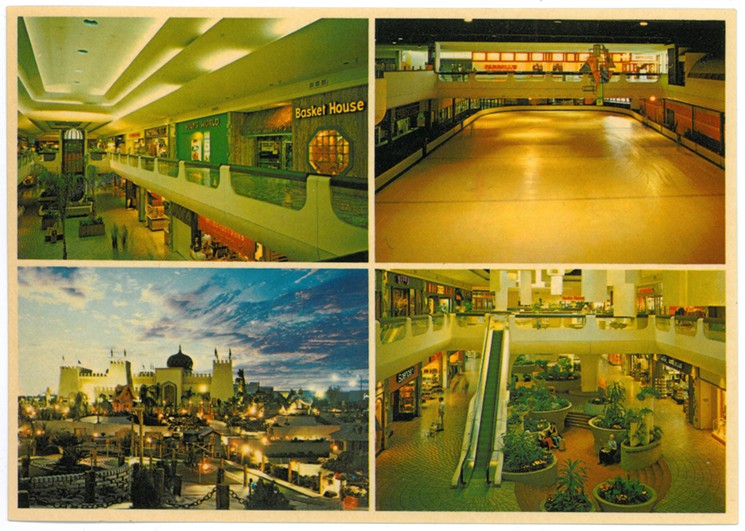

“They ruined the mall, mijo,” says Ernie Silva, for whom Metrocenter was a home away from home in the 1990s. “They tore out all the eucalyptus trees, so there was no more shade to park in. There used to be these beautiful conversation pits where you could rest or meet your buddies or whatever. There was glitter in the walls. One whole wall was fossils. Remember those big, swoopy arches at all the entrances? And inside they had a fountain that went all the way up to the ceiling from the bottom floor, and you could throw pennies in and make a wish. It was like some kind of pleasure dome for kids. They tore it all out and made the place look like a cheap copy of Arrowhead.”

Local artist Randy Slack agrees. “Dude, the original architecture of that place was so cool,” says Slack, who grew up 2 miles from Metrocenter in the 1980s. “All those rounded curves and the art nouveau elevators. Even the trash cans were sculptures.”

Slack says he often feels like he spent his whole childhood at Metro.

“I was a mall rat,” he says. “I ice-skated and played hockey there. I ate at Farrell’s Ice Cream Parlor with the funny loud music. You could spend a whole day doing nothing, with no money.”

Tracy Smith remembers how far $10 could take you at Metrocenter in the ’70s. “I bought a shirt, a 45 record, and I went to Farrell’s and got a jaw breaker and a red rope for lunch. Try doing that today.”

Smith recently co-founded that Facebook page devoted to Metrocenter’s glory days; in its first week, it logged more than 16,000 sentimental new members. “Everyone from the west side has a Metro story,” she says. “I got my first pair of high heels at the Broadway there. My mom got her first charge card there, at Goldwater’s, and she used to hide the bills from my dad. She paid $100 for my graduation dress, and that was a super-huge deal back then.”

When she was just 15, Smith lied about her age to score a Metrocenter job making belts and barrettes at Brockman’s Leather. “All the cute rocker guys would come in and buy leather bracelets and skull earrings,” she recalls. “That’s how I became a metalhead. I got my identity at Metro, and I still have it. Metro could change your whole life.”

The only time he ever ditched school, Steve Hrovat says, he made a beeline for Metro. “I got there and realized how boring the place was when all your friends were in school,” says Hrovat, who graduated from Cortez High in 1986. “So I headed back to school. And the worst part is that nobody had even noticed that I’d been gone.”

Silva and his buddies used to panhandle in the mall. “We had this really ugly guy named Oni,” he confides, “and he’d go up to people and say he needed a quarter to call his mom to come get him. He was so ugly, they’d feel sorry for him and give him extra. One Saturday, Oni made like $20, man!”

“We grew up and Metro grew up with us,” is how Debi Davis sees it. She worked at the Metro Sears store; later, one of her sons worked there, too. “You went from shopping with Mom there to hanging out there with friends to cruising the circle to working there. My kids took the bus there and spent the day and it just felt like they were going someplace safe that I knew really well.”

Rebecca Miller, a paralegal who graduated from Alhambra High in 1981, wouldn’t have let her kids hang out at Metro. “But then I wouldn’t have dropped my kids off anywhere,” she says. “I raised them when there were little faces on milk cartons. I wouldn’t let them out of my sight when we went to the grocery store. I practically lived at Metro, but the world where kids could spend the day at the mall is gone.”

Hrovat thinks so, too.

“If my kids wanted to go hang out at Arrowhead Mall, my wife and I would have 200 questions for them,” he laughs. “I remember being at Metro with a friend of a friend who said to me, ‘What should I steal, and from what store?’ That wasn’t cool. And I certainly wouldn’t let my kids go cruising. Not that cruising is a thing anymore.”

Cruising Metrocenter was very much a thing in the late ’70s and early ’80s. When Phoenix Police cracked down on horny teens who coasted up and down Central Avenue on Friday and Saturday nights, the kids moved the whole operation to Metrocenter, where they circled the mall for hours every weekend night. There, engines were revved, boredom was briefly banished, and — if you were really lucky — sexual tension was relieved.

Davis cruised Metro almost every weekend. “You’d run into your friends, go to Golf and Stuff, meet new people. Some of it was sex. If you hooked up, you’d leave the mall and go to someone’s house, I guess.” She pauses for a moment. “I mean, I never did that.”

Cruising was a starting point, according to Smith. “We connected there and went and did something else. Usually I was looking for a party, or some kind of hell-raising.”

Slack agrees. “You never planned your night around ‘Hey, let’s cruise Metro!’ It was more like when the party you were at got busted, you’d go cruise. It was your fail-safe. It was always there. Some people had really great cars to show off, but most people were in their old beater or their mom’s Ford. Of course you were cruising for chicks. I guess we can’t call them chicks anymore. But they were chicks back then, and they were cruising for dudes.”

Cruising wasn’t all fun and games. Slack remembers a heavy police presence, and an annoying three-lap rule. “If the cops saw you go past three times, you got a ticket. I know I sound like an old man, but why were they hassling us? We were a bunch of kids who couldn’t have been in a safer place, driving around in a circle with police as chaperones. Does it seriously get any safer?”

He also recalls getting busted with a 12-pack of beer. “The cops made me pour it out. I was crying, like, ‘Do you know how hard it was for us to get 12 beers?’ But now, looking back, I realize they were teaching us a lesson. Today they would just haul a kid in, no lesson learned. In a way, that mall kind of raised us.”

Silva also learned some life lessons cruising Metro in the early ’80s. “I already knew white guys didn’t like me because I was brown,” he explains. “But I kind of didn’t know how the police could treat you different.”

When he and his buddies cruised their lowriders through Metro on Friday nights, Silva says they were singled out by police.

“You’d go around once and they’d pull you out of the line and try to ticket you,” is how he remembers it. “My older brother had this chromed-out Bonneville, very sweet, and he’d just show up and the cops would be on him. One time a white kid threatened to kill him, and after that we just stopped going. I mean, nobody goes to a shopping mall to die, am I right?”

Occasionally, they do. Talk to anyone about Metrocenter for more than a few minutes and you’ll likely hear about the woman who killed herself there.

“Everyone has heard that story,” Hrovat agrees. “She supposedly jumped off the second floor onto the ice-skating rink. But it’s the kind of story you hear, and you assume it can’t be true.”

Not only is the story true, says Sandy Voris, but it wrecked her 17th birthday party.

“I was celebrating with two or three friends,” remembers Voris, who graduated from Greenway High in 1978 and today works as an administrative assistant in a Phoenix church. “It was mid-afternoon, January 23. We were just skating around, not a very big group of us. I heard a gasp and a scream, and suddenly there was a person in front of me, prone on the ice.”

According to a brief next-day account, buried at the bottom of page 41 of the Arizona Republic, 39-year-old Mary Anne Rosenberg was in the company of her young daughter and “a male companion” when she leaped from a second-floor walkway 25 feet above the ice rink. Rosenberg, the story claimed, had attempted suicide before.

“I didn’t see her fall,” Voris says, “so I thought she’d fallen over on her skates. I got closer and saw that she was wearing high heels, not skates, and I realized what had happened. You never saw an ice rink clear so quickly. People were literally throwing their skates off, running for the pay phones to call someone to come get them out of there.”

Taken to John C. Lincoln Hospital, Rosenberg died in the ER from extensive head and neck injuries. She passed immediately into Metrocenter folklore.

“I was there and seen the whole thing,” says John Shedler. “Myself and my friends was standing up top watching the ice skaters. The lady got in a verbal altercation in the airplane bar and came out and ran up to the rail right next to us and jumped.”

Kris Wright was at Metro that day, too. She remembers there was still “blood and tissue and hair on the ice,” but the rink remained open. “Someone put up orange cones around the area where the body had been,” Wright remembers with horror, “and people were still skating around. I didn’t go to Metro for a long time after that.”

It wouldn’t be long before not going to Metrocenter became a popular thing to do.

It’s just after 9 p.m. on a Saturday night in July, and in a crowded hunk of Metrocenter’s parking lot, a trio of women in hot pants are rubbing their torsos against a red sports car. As the auto moves in slow, sleepy circles, the women straddle the hood and trunk of the car, gyrating their pelvises and hooting. A man breaks away from the crowd and spanks one of the women as she drifts past. Everyone cheers.

No one in the teeming crowd, which will later be estimated at more than 18,000, appears to find this display offensive. “We’re just having fun,” says a bearded man in a Ted Nugent T-shirt stretched over his ample belly. “Reliving our best lives.”

Metrocenter has officially been closed for four days, but tonight it’s thronged with locals looking to drink beer and watch cars drive around in circles in the company of people they haven’t seen in decades. A shiny black truck draped in an American flag roars past, smoke billowing from its wheels and tailpipe. A group standing nearby begins chanting: “Do-nuts! Do-nuts!” Behind the truck comes a man who has pasted to the side of his car a giant copy of a traffic ticket he received for cruising Metro some 40 years before. A woman in a crimson Make America Great Again cap hugs the man standing next to her. “This is so cool!” she yells into his ear.

Around the corner, a group of former mall rats perform a line dance to Tag Team’s “Whoomp (There It Is).” Behind them, a giant video screen flashes old photographs of Metrocenter and commercials for Hot Dog on a Stick. Pretty much no one here is wearing a COVID mask.

“I needed to take a nap to stay up this late,” says a woman whose gray hair hangs to her waist. “But it was totally worth it!”

Somewhere in this crush of suburban sentimentalists is Tracy Smith, who accidentally caused this event to happen.

“I figured I’d get maybe 10 of my friends to show up when I said we should do one last cruise of Metro,” says Smith, who graduated from Thunderbird High in 1986 and still lives in the area. When Smith created a Facebook page for the event, it exploded.

“Within an hour there were 1,000 people signed up,” she says. “And my phone didn’t stop pinging for three days. I thought, ‘Holy shit, what just happened?’”

This hotrod-humping, parking-lot party is the second “final” cruise of Metrocenter. The first, held the Tuesday before, marked the mall’s last day of business and attracted nearly 15,000 people. The next morning, Smith was bombarded with requests for another cruise. By then, she’d relinquished the reunion reins to a couple of guys she’d met on the event’s Facebook site, who were already planning Saturday’s event.

Smith also heard from grateful strangers. One woman who’d been ill for some time emailed, “You gave me one night to live my life again.” Another man wrote that he was nearly suicidal but said cruising Metro one last time had given him something to live for. “He went and reconnected with people he hadn’t seen in ages,” Smith reports, “and now he’s not in that dark place anymore. I couldn’t have planned on any of that.”

One thing Smith did plan on was her own Metrocenter finale. “One of the guys I ran with at Metro died in January,” she says through tears. “I took some of Bart’s ashes with me on Saturday night, and when I was taking my final lap, I cranked up Poison’s ‘Talk Dirty to Me,’ rolled down my window, and spread some of his ashes on the loop as I drove away. That was pretty cool. Bart will forever be part of Metrocenter now.”

Smith stops to wipe away tears. “Of course, people were probably looking at me going, ‘What’s coming out of the window of that lady’s car?’”

Where some saw a crowd of strangers bonding, others saw something more antagonistic at Metro’s farewell cruise.

“I worried that the cruise was a kind of unintentional response to the current political climate,” Michael Hooper confesses. “There weren’t a lot of people wearing face masks, and they made such a big deal about the police at the end of the evening.”

Hooper, an industrial packaging salesman who grew up on the west side, is referring to the parade of squad cars that cruised by, their lights flashing, while thousands lined up to cheer, with no irony, the same squad that tried to keep them from cruising 40 years before.

“I hope that cheering the cops wasn’t a snub to the Black Lives Matter movement,” Hooper says. “But, you know, this was a group of predominantly white, working-class people who appeared to have an affinity for the current administration. So it kind of looked that way.”

Local film critic Mark Moorhead is more to the point. “Most of the people there looked like they’d come straight from a Trump rally. This was as un-socially distant a group as you could get — maybe one in 20 people was wearing a mask. They were calling it a ‘last cruise,’ and I was thinking how for many of them, their last cruise might be in an ambulance once they got COVID.”

Rebecca Miller sees it differently.

“The TV news stories didn’t do justice to what was happening in the parking lot on those two nights,” Miller complains. “They talked about our old memories and how cool the mall used to be. They didn’t see that we created a community of 15,000 people from all over the world, who became best friends almost overnight.”

Those friends showed up at Metrocenter the morning after each cruise to help clean up the mess left behind, according to mall manager Ramirez. And dozens more signed up to help Metro tenants move out of the mall last week.

Miller heaves a sigh. “It’s hard to explain,” she says. “We’re a group of strangers who became something bigger than just a mall closing.”

Moorhead says he stumbled on those final cruisers while picking up dinner for his daughter. “I was looking at the throngs of people and thinking, ‘Where the fuck were you when this place needed customers?’”

Moorhead continued to shop at Metro even after he and his family moved out of the area several years ago. “I walked around Metro a few weeks ago while my kid was having her brows waxed, and the place was a mausoleum. There was the occasional old person making their daily laps, that’s it. That mall meant something to me. I’m sorry to see it go.”

In the end, Moorhead thinks, there’s no mystery about what killed Metrocenter. “It was white flight. Neighborhoods take on color and white people flee farther into the ’burbs. Metro got forgotten by white people, at least until it was time to close it. Then it was, ‘Poor us! Our whole life happened there! Let’s have a party!’”

White flight, says Dr. Michele Marion, a professor of sociology at Paradise Valley Community College, can be both sociological and economical.

“If you have the economic means, you can choose not to live next door to someone who is ‘other,’” she explains. “You can flee. In Phoenix, we’re seeing white flight wrapping itself back around, because everyone is moving back to the downtown urban center and pushing out people with less economic means who’ve been living down there since it was abandoned in the ’60s.”

People like to think they’re diverse, Marion says, and comfortable with heterogeneity. “But are they? It’s not in our nature to want variety, surprise, things that are unexpected. Homogeneity makes us feel safe by not presenting anything that’s ‘other,’ and it makes us feel efficient, because we’re not being challenged.”

If shopping malls are microcosms of the world, Marion posits, then a Metrocenter is safe and comfortable because white people unwittingly see it as a secure place for kids where they can get all their shopping needs met in one place.

“Then people of color move into the neighborhood, or start shopping where you shop, and those who can afford to will often go somewhere else,” Marion says.

The more diverse demographic of the area definitely changed Metrocenter, says Joi Whitley, co-founder of Black Entrepreneurs Alliance of Phoenix. “That mall had a history of racial profiling, of not making all people feel welcome.”

Now that Metro is for sale, Whitley’s group hopes to purchase it sometime in the near future. A Black-owned Metrocenter, she contends, would be welcoming to all people and therefore couldn’t help but succeed.

“We’re still in the initial stages, trying to raise money,” she says. “We want to make sure we have things in order, get a board together and such.”

Debi Davis hasn’t heard anything about a Black group buying the mall. “I saw a story where this other mall, I think it was somewhere overseas, got turned into a place for Alzheimer’s patients. That seems like it could be good.”

Someone on the Metro Facebook page thought the mall could become a nice school for special-needs kids. Someone else said Metro should get redone as an indoor go-kart raceway. Yet another person pointed out that nobody in the group was getting any younger, and maybe Metro would make a really cool senior housing facility.

“I can just imagine that,” Rebecca Miller says with a laugh. “We’d all be living in our favorite stores. ‘Hey, can you guys tell me where Rebecca lives?’ ‘Oh, she moved into B. Dalton Bookseller — next door to Teri and Tracy at Hot Topic.’”

Smith sort of likes the idea of living at Metrocenter. “Hey, it makes sense,” she says, warming to the idea. “Back in the day, Metrocenter was our home away from home, anyway. So why not live there? Because in the end, Metrocenter was the house that built a lot of us.”