Audio By Carbonatix

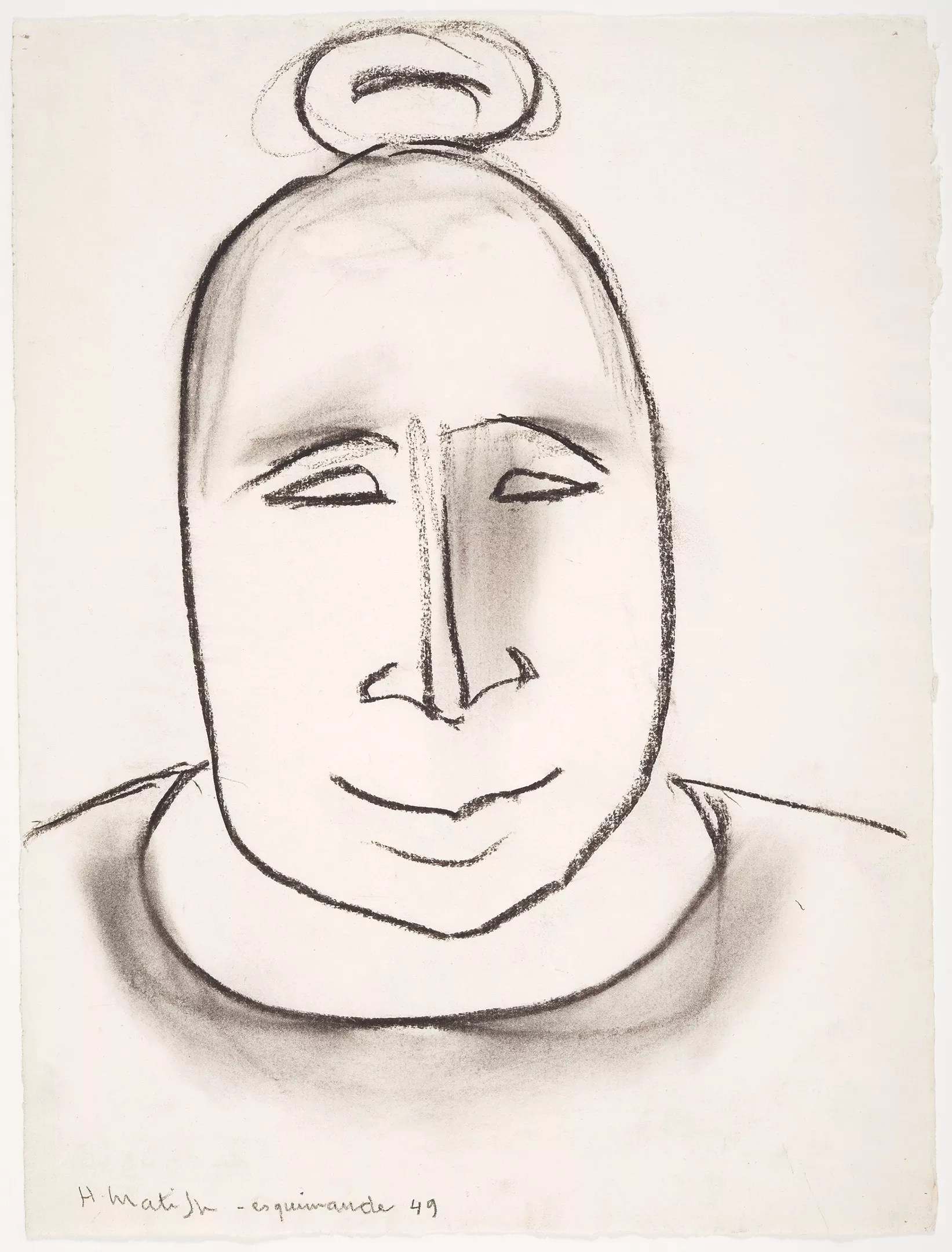

When someone mentions famed French artist Henri Matisse, one might recall La Danse, his fluid circle of five dancers painted in 1910, or the large paper cutouts imbued with floral designs he created in the late 1940s. But there’s a fascinating part of Matisse’s body of work that’s received far less attention through the years: portraits inspired by Inuit masks, which are part of a new exhibition at the Heard Museum.

“There’s a little-known connection between indigenous peoples of the Arctic and the famous 19th-century artist,” says David Roche, director and CEO for the museum since early 2016. “I learned about the connection in 1998 through a Matisse family member.” At the time, Roche was working at the famed Sotheby’s auction house in New York City.

“When I started at the Heard, I thought about what are the great stories that need to be told,” Roche recalls. “This is one of them.” Hence, the museum’s latest exhibition titled “Yua: Henri Matisse and the Inner Arctic Spirit,” which runs through February 3, 2019. “Yua” comes from the Yup’ik people, Native Alaskans for whom the word connotes “the spiritual connectedness of all living things.”

The exhibition includes original Matisse artworks and Yup’ik masks, in addition to cultural objects, photographs, film, and ephemera. Some of the Matisse works have never been shown publicly in the United States before, and several of the masks are being shown in pairs as intended for the first time in over a century.

The artworks and objects were gathered on loan from various museums and private collections, both here and abroad, and the Heard Museum is the sole venue where this exhibition will be shown. It’s co-curated by Sean Mooney and Yup’ik artist and elder Chuna McIntyre.

Visitors may find the story sounds a bit esoteric until they explore the back story, which includes Matisse’s fight against cancer and his daughter’s fight against Nazi Germany as part of the French Resistance. Matisse fled to Nice, on the Riviera, in 1940, the year Hitler invaded France. It was there that the artist, at that point in his 70s, underwent cancer surgery, which he barely survived.

“After 1941, Matisse looked at everything as extra time,” Mooney says. “He did a completely new body of work, including his cutouts.”

Matisse also worked on designs for the Vence Chapel, and a series of drawings inspired by his son-in-law’s collection of Inuit masks. “After 1945, Matisse begins to refer to his portraits as masks,” Mooney says.

The exhibition includes dozens of Matisse drawings on paper, created using pencil, ink, charcoal, and other media. It also features dozens of masks made with wood, pigment, feathers, grass, baleen, hide, sinew, and other natural elements. “My hidden agenda was to present the Yup’ik masks,” Mooney adds.

Central Yup

NMAI Photo Services

“The masks were made for seasonal dances, which comprise a kind of visual storytelling with comedic and theatrical components,” Mooney explains. “But the dances also have a spiritual component and the shaman is considered the artist.” Often masks were created in pairs, although most sets got separated over time. “We’re showing at least a dozen related groupings, which haven’t been seen in public for more than 100 years,” Mooney says. “The presentation of the Yup’ik masks is very powerful.” Roche agrees, citing the masks’ sculptural qualities. “Yup’ik masks are very beautiful, psychologically complex, and otherworldly,” he says.

Turns out, Matisse had a longtime fascination with masks. “Matisse had been fascinated with the concept of the mask from early in his career,” Roche says. Roche notes that most paintings done before the early 20th-century were either portraits or landscapes. But Matisse, who’s considered the father of modernism, gave portraits a new twist.

“Matisse inserted a mask in lieu of a face for one of his artworks around 1918,” Roche says. “It was revolutionary at the time, and it represented a fascinating disruption in traditional ideas of what a painting should be.” Exhibition materials provide insights into masks as metaphor and social construct.

Artworks and other objects are exhibited in several different sections of the exhibit, where viewers can read text panels that provide context and illuminate important connections between Matisse and indigenous cultures. It’s those connections that form the real heart of this exhibition, according to Roche.

“The heart of the show is setting masterworks from two different cultures side by side, which demonstrates that there’s a creative force that unites us all,” Roche says. “At a time when things feel so divided in the world, the exhibit is especially timely and important.”

“Yua: Henri Matisse and the Inner Arctic Spirit.” On view through February 3, 2019, at Heard Museum, 230 North Central Avenue; 602-252-8840; heard.org. Free with museum admission, which is $18 for adults.